This may sound like an odd complaint, but I've been seeing a lot of plays recently with nobody to root for, no characters I care about enough to want the play to come to a good conclusion for them. I mean, you can hardly cheer on old King Lear, can you? Even in Simon Russell Beale's masterly embodiment of the old reprobate who can't see that his daughters are spoiled monsters who will reject him and all his gifts, he comes over as more sinning than sinned against. His Lear is a Stalin-like figure who interrogates his family as if he were a Senate committee chairman and they an offending tobacco or oil company facing him across a committee room to answer his questions about whether and how much they love him. After that, even as he loses his reason, you can't warm to him.

I never realized before that what Shakespeare has written is an exact and exacting portrait of dementia, one of the most intractable problems of our day as well as his. The Tragedie of King Lear is indeed tragic as Lear descends into his own fractured world, his vision narrowing to contain only his own befuddled senses, and in the process losing the wider picture. Sam Mendes and Simon Russell Beale, together again, have created an unforgettable portrait of a man losing himself but he is hardly, even at the end, a sympathetic one.

The Mistress Contract at the Royal Court is certainly not Shakespeare, but its two characters, meticulously played by an exemplary Saskia Reeves and Danny Webb, seem to me an extreme example of a play with no sympathetic characters. The premise is interesting but in a distancing way. It is the apparently true story of a man and a woman on the West Coast who make a lifelong arrangement that he will provide her with a home and an income, while she will provide "all sexual acts as requested, with suspension of historical, emotional, psychological disclaimer." It sounds horrible but can't be as bad as it appears in the play, as it has continued for some 30 years and the real people concerned are now 88 and 93. The play is based on recordings the couple made throughout their relationship of their conversations, which they turned into a book and which Abi Morgan has now adapted for the stage.

| |

|

|

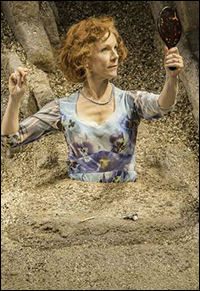

| Juliet Stevenson |

I'm not arguing here for mindless entertainment. The theatre is not, nor should it be, a fluffy way to spend an evening on the way to dinner. To think, to feel, to recognize oneself in another person, to reevaluate, to be challenged, all these are the responsibility of good theatre. But so also are plots, situations, and characters to believe in and identify with and there's the current rub — the identification bit. I would suggest that all plays, whether musical or not, no matter their period or setting, have to have the "me too" factor. In other words, there should be moments, even if the play is set in medieval Russia or on another planet in the future, when the audience thinks, "Yes, I feel that, too." If there is no "me too" factor, no identification with any character, the play becomes merely a spectator sport. Engaging with the characters is central to our understanding of what the play is about and if there is nobody to engage with, it is just an intellectual exercise and something of a dry one at that.

| |

|

|

| Tim Dutton and Mark Arends |

But there was some light in my tunnel this month. One of our finest and most versatile dramatic actors displayed a talent for comedy that nobody, including me, thought he had. Tim Pigott-Smith, known to us for his Shakespeare, O'Neill, and Albee performances, is playing dark high comedy in Larry Belling's Stroke of Luck and having the time of his life doing it. He plays a stroke victim who announces at his wife's funeral that he is going to marry his sexy Japanese nurse. His three dysfunctional grown-up children are horrified, especially when they discover that this television repairman has, improbably, become a millionaire fixing equipment for the Mafia, and set out to prevent the marriage at all costs. Larry Belling's nimble comedy gives each of the characters a believable background and manages to keep us interested in all of them and, in a funny way, to care about all of them despite their greed and general uselessness. Once Belling and Stroke of Luck has accomplished that, the improbability of the final plot twist becomes a felicitous flight of fancy rather that a Lear-like downer. Oh, and did I say it's very funny? Not a lot of laughs in King Lear.

(Ruth Leon is a London and New York City arts writer and critic whose work has been seen in Playbill magazine and other publications.)

Check out Playbill.com's London listings. Seek out more of Playbill.com's international coverage, including London correspondent Mark Shenton's daily news reporting from the U.K.