*

I think the Royal Shakespeare Company must be getting tired of people like me complaining about the trains from London to Stratford-upon-Avon. So, like the mountain coming to Mohammed, they are coming to us. No sooner had they announced an ambitious plan to take over New York's Armory next summer and turn it into a replica of their Courtyard Theatre, but they tell us they are coming to London in November with six full-scale Shakespeares, two children's cut-down Shakespeares, a cast of 44 in 228 roles, performing in yet another replica of the Courtyard, this time at the Round House, a dearly loved London space which used to be a railway turnaround and is now an innovatively designed theatre. While the RSC's home in Stratford is being rebuilt, they're spreading their wings and flying away to distant parts, well, London and New York are fairly distant, and, if all goes according to plan, there will be three functioning Courtyards by the middle of next year.

***

|

||

| Nancy Carroll and Benedict Cumberbatch in After the Dance |

||

| photo by Johan Persson |

Frocks are lovely, acting top-notch, and the sight of all these rich folks drinking themselves to death doesn't sicken so much as warn at a time when the philosophy of grabbing whatever you want, now, no matter at whose expense, is more prevalent even than it was in Rattigan's day.

***

The frocks were pretty lovely at the saddest event I attended recently — the last ever performance at London's premier, no, only cabaret room, the Pizza on the Park. This black-tie evening was as studded with tears and diamonds as it was with stars. It was so easy to pass the door unnoticed; it was located below an upmarket pizza joint and you could actually sit upstairs and eat your pizza without having any idea that downstairs there were the cream of American and British cabaret artists singing their hearts out. It was appropriate that the final artist to play at the Pizza before the developers pull it down and build (oh joy) yet another hotel, was the classy American singer-pianist, Steve Ross, who has played the room (and sold it out) every year of the 27 it has existed. Karen Akers was here this week, so was Andrea Marcovicci, and an audience crammed with lovers of the songs of Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, Dietz and Schwartz, George and Ira Gershwin, and all the other greats of the songwriting world. Now their voices are, I hope temporarily, silenced in London and the audience of addicts, in which I include myself, are cabaret orphans.

|

||

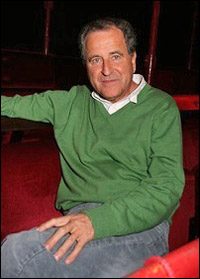

| Artisitic director Nicolas Kent |

Grouped into two sets of plays, titled Then and Now, Nicolas Kent and his director, Indhu Rabasingham have commissioned virtually every British female playwright to write a short play on some aspect of women's lives.

The plays are inevitably uneven. Some, like Moira Buffini's Handbagged where two Margaret Thatchers (Stella Gonet and Heather Craney) and two Queen Elizabeths (Kika Markham and Claire Cox) battle it out for supremacy, and Joy Wilkinson's Acting Leader, where Margaret Beckett can't quite believe in herself or get her colleagues to believe in her enough to fight for the leadership of the Labour Party after John Smith's death, are touching and illuminate something in the female character which might explain both the steely determination and the self-doubt in every woman. Some, like Marie Jones' The Milliner and the Weaver and Rebecca Lenkiewicz's The Lioness, about Elizabeth the First, are historical documents in their own right.

The plays are cross-cast with 15 phenomenal actors led by Stella Gonet, Kika Markham and Niamh Cusack, each of whom, seemingly inexhaustibly, pops up in every, or at least every other, play, taking the roles of women from all over the U.K. of every class and background, of every political strike and none. There's even one play with an all-male cast, Zinnie Harris' The Panel, where a board of men is deciding on female candidates for a job in their department.

Interspersed between the plays are edited interview snippets with real contemporary politicians of different stripes from Jacquie Smith to Shirley Williams to Ann Widdicombe. In each case, an actor you saw moments ago as an Irish firebrand or a Greenham Common mum, is transformed into women we know from our television news, telling us about the real life of a woman politician today. Fascinating. But it doesn't explain why, when we've come so far in 40 years, the ground we've covered is so limited. ***

The War is over. The British, so brave in combat, so indomitable when having the bejesus bombed out of them, so sure that what they were fighting for was right, are now expecting their rewards for a job well done. And, somehow, it doesn't come. Even for the better-off — a doctor's family for example — life is a struggle. Instead of the life of plenty they believed would follow Hitler's defeat there is food rationing and the austerity of a post-war economy. Their world is dark and mean, no eggs, no fruit, no nice clothes, just making-do. Wait a minute, didn't we win the war? For a child growing up in such a family this is normality and if, as in Holly's case, he has enough to eat, schoolwork he likes, a growing sexuality to explore, and a warm relationship with his music teacher, what could possibly be wrong?

|

||

| Helen McCrory and Laurence Belcher in The Late Middle Classes |

||

| photo by Johan Persson |

The most English of playwrights, Simon Gray, with the gleeful connivance of Helen McCrory, manages to make embarrassment and boredom additional characters in his play. But he had a deeper purpose when he wrote The Late Middle Classes in 1999, in that this most domestic of post-war dramas exorcised his own childhood and his conflicted relationship with his own mother.

(Ruth Leon is a London and New York City arts writer and critic whose work has been seen in Playbill magazine and other publications.)

*

Check out more of Playbill.com's international coverage, including London correspondent Mark Shenton's daily news reporting.