This is the time of year when my legendary sunny personality turns grumpy. The reason? In a word — pantomime. One of the best months of the year for openings turns overnight into a theatrical desert in which common sense, artistic taste and intellectual rigor disappear into a welter of bathroom jokes, television comedians and painted canvas animals with two men inside them. In this country we have so little respect for our children that we subject them, every Christmas, to these appalling entertainments full of sexual innuendo, which they don't understand, and bad scriptwriting that is excused by labeling it traditional.

For those readers across the Atlantic who are lucky enough never to have been in England during "panto" season, I should explain. I can give you a lot of guff about how it grew out of commedia del'arte in the 16th century — touring companies of actors around Europe performing simple plots with stock characters, such as Harlequin, Columbine, Pantaloons and Pierrot — and how it subsequently developed from dumb show to spoken and sung entertainments in the 18th century, and what happened to it after that, but what it has now, in the 21st century, developed into is what I think of as a specifically English form of theatrical torture.

Fairy tales — "Babes in the Wood," "Snow White," "Cinderella," "Ali Baba," and so on — are purloined by theatre companies the length and breadth of Britain and served up to the nation's children, decorated with terrible songs, to many of which the kids are asked to sing along, as theatre. Children are encouraged to shout back at the characters and are very often brought up on stage as part of the action. There is a large cast of singers and dancers, specialty acts that have nothing to do with the plot (they're often the best bits) and as much sparkle and spangle as the hard-pressed theatre can afford.

The tradition is that the two leading roles are always played by actors of opposite gender. The Principal Boy is usually a pair of female legs attached to a delectable form that has competed on "Strictly Come Dancing" or some other reality show, while the Dame is usually a well-known burly comedian with hairy legs wearing shock-horror dresses which he changes with every scene. This is often the character whose script, while pretending to entertain the children, is replete with sexual images meant for their parents. For reasons I have never fathomed, sometimes great actors queue up to play these roles. On one recent year, Ian McKellen was the Dame and Roger Allam played Abanazer in a specially mounted (and sold out) production of Aladdin at the Old Vic, no less.

Every town and city has a panto in even its most respectable theatres at Christmas. It is as though the collective taste of the theatre-going public has been temporarily amputated for the six weeks of the festive season. The performers are indeed professionals but so tightly are they bound into the conventions of panto that even the experienced stage actors cannot demonstrate their art for the kids and, these days, the Dame and Principal Boy are usually performed by television stars who have never been on a stage before. But the real problem is that these shows, which are neither real musical theatre nor plays, are in almost every case the only live theatre that England's children will get to see all year. I would have no objection if they were simply part of the rich tapestry that is British theatre, seen alongside many other shows during the year, but for many these are the only experience they will have until they are adults. No wonder the theatre is declining among the young.

It should also be stated, as firmly as possible, that London particularly and our other big cities as well, produce wonderful theatre for children and young people throughout the year. It is harder to find audiences for these brilliant, thoughtful, and humorous productions because there is no longer the habit of taking children to the theatre from an early age. Except, every Christmas, to a panto.

I thought pantos were silly, unfunny and boring when I was six years old and I still do. So, as Scrooge would say, "Bah, humbug!"

| |

|

|

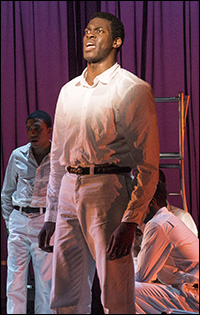

| Kyle Scatiffe in The Scottsboro Boys. | ||

| Photo by Richard Hubert Smith |

Also pretty darn good is the new revival of Jez Butterworth's breakthrough play Mojo which, to my knowledge, has never crossed the Atlantic but, with the success of the same playwright's Jerusalem, may well travel now. Like Jerusalem, Mojo is a "state of England" play, a close look at an even smaller canvas, the underbelly of petty criminals in a seedy bar in London's Soho in the mid-1950s. Against a backdrop of the development of rock 'n' roll and the emergence of the teenager as a separate entity from either adults or children, the explosion that would become British rock, leading eventually to the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, was breaking out in many directions. Dozens of these small bars hosted any kid who wandered in with a guitar and wanted to sing. What had been big business controlled by record companies became a local affair with every dead-beat trying to make a quid from the few really talented boys (and they were all boys) who showed up.

Mojo gives us a perfectly-cast assortment of these young hangers-on, a performer called Silver Johnny, and an older sinister bar manager (Brendan Coyle, whom American viewers will know at Mr Bates in "Downton Abbey") on one shocking Sunday on which their boss is murdered and they are cast adrift on their own slim resources. The only other actor who would likely be known to American audiences is Rupert Grint, finally shucking off all traces of "Harry Potter" and giving a finely nuanced performance as Sweets, the most easily-led of an easily-led bunch. Ben Whishaw is magnificent as the psychotic son of the murdered owner and Daniel Mays and Colin Morgan are both extraordinary as teenage employees of the bar, with hopeless aspirations in the nascient rock world.

What Butterworth and his director Ian Rickson achieve with Mojo is nothing less than a snapshot of an England at its moment of fragmentation. Its relevance (horrible word, necessary here) is that the exact pattern of fragmentation is repeating itself right now as the music industry, as a metaphor for many others, struggles to free itself for a future without the stranglehold of big business. In among the whales, the minnows are jockeying for position, just as they were in the 1950s.

The big musical, bigger even than The Scottsboro Boys, is Tim Rice's From Here to Eternity. It isn't just Tim Rice's, of course; it has music by Stuart Brayson and a book by Bill Oakes, adapted not from the famous film starring Deborah Kerr and Burt Lancaster, but from the original novel by James Jones. Set in Hawaii during the Second World War, it focuses on two love affairs, one between the wife of the Commander of the American base and her husband's second in command, the other between a prostitute and a marine. The work, the effort, the sheer skill of this show is evident in every scene. The huge cast performs Javier de Frutos' choreography with precision and dedication, and the scene of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour is brilliantly engineered. Some of the songs are fine, and everybody sings them well. There were some casting and direction problems on press night, but they may have been ironed out by now. But the problem of any show based on a real-life event is that we know how it turns out. With The Scottsboro Boys we had come to know them by the end, and their tragedy was ours. With From Here To Eternity, that's less true.

(Ruth Leon is a London and New York City arts writer and critic whose work has been seen in Playbill magazine and other publications.)

Check out Playbill.com's London listings. Seek out more of Playbill.com's international coverage, including London correspondent Mark Shenton's daily news reporting from the U.K.