*

For years after the opening of the concrete mausoleum on the South Bank of the Thames, otherwise known as the Royal National Theatre, it didn't know who it was or what it was for. It had (for the 1970s) state of the art technology which nobody seemed to be able to work and a fuzzy mission which nobody really understood. But look at it now. Just this month alone, it's tackling O'Neill and Tennessee Williams, Jacobean tragedy, an 18th century comedy, Bulgakov's Russian family saga, and at least one cutting-edge contemporary play.

|

||

| London's National Theatre |

Just being in the National on an average night is a kick. The other evening I asked a woman sitting in the lobby with a glass of wine which play she was seeing and she replied, "Oh, none of them. I often come here after work to have a drink and listen to the music. It's so lively and fun and I get to find out about the plays from people like you. So," she continued, "what should I see next?"

She should certainly see Marianne Elliott's new production of Thomas Middleton's 1622 Jacobean drama, Women Beware Women, running to July 4 at the National's Olivier Theatre. Manipulation is the tool, power is the end, sex is the currency. In fact, they're all in there just waiting to be exercised by people who think the rules don't apply to them. Think television stars, professional golfers, politicians, and my personal favorites, bankers. Greed and sex, the twin preoccupations of our celebrity culture, turn out not to be of our generation at all but the equal currency of all those who have gone before.

|

||

| Lauren O'Neil and Samuel Barnett in Women Beware Women |

||

| photo by Simon Annand |

All are arranged by the rich widow, Harriet Walter (she was Tony nominated last year for Mary Stuart) as the most perfect villainess — you almost expect her to hiss and twirl mustachios at the audience — who, with her assistants, organizes first the alliances and then the downfall of every one of them, including eventually herself. The toffs (for which read footballers, golfers, politicians, and, yes, bankers) trumpet their entitlement to anything they want, whether it's a girl or a palace.

Director Elliott has cleverly set the play in the 1950s, a time when class was breaking down and nobody "knew their place" any more, thus giving the lower orders a taste of the possibilities that might be available to them if they could just vault the class divide. She finds humor in gesture as well as lines and in this play that's a major achievement because, let's face it, Thomas Middleton is hardly Oscar Wilde in the wit department.

The final scene, when, in true Jacobean style, everybody murders everybody else, works brilliantly as the problem of unlikely multiple murders by all too likely murderers is here solved by being folded into a macabre ballet with the Olivier Theatre's enormous turntable revolving overtime to expose yet more bloody death. The technology works!! A rollicking, if gory, evening and another triumph for the National.

If the National's Olivier is for exploring large-scale dramas with huge casts and top-heavy technical feats, the little Cottesloe is for looking minutely at miniatures. With its own separate lobby and flexible seating, the Cottesloe is where you go for the rediscovery of a forgotten gem or a difficult new play. I'm not sure which category Beyond the Horizon (through June 19) and Spring Storm (through June 22) fit into because, although one won a Pulitzer Prize and both are by America's greatest playwrights, neither had ever been played in England before nor, for the most part, anywhere else. So, a rediscovery or a new play?

In his later plays, in the great ones, especially Long Day's Journey Into Night and Mourning Becomes Electra, Eugene O'Neill skirts the boundary of melodrama, but he never crosses it. O'Neill knew a lot about melodrama. His father was a famous barnstorming actor who toured the United States over and over again plying his trade and making his living as the Count of Monte Cristo. Melodrama also infused his family life: His mother was addicted to painkillers, his brother drank himself to death, and he himself suffered from both alcoholism and tuberculosis. Inevitably, in his first full-length produced play, Beyond the Horizon, the inexperienced playwright falls headlong into it, which didn't stop him from winning his first Pulitzer Prize.

|

||

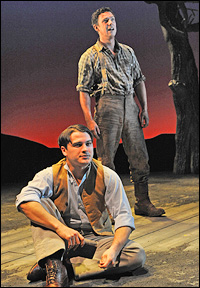

| Michael Malarkey and Michael Thomson in Beyond the Horizon |

||

| photo by Robert Day |

Beyond the Horizon is a little too patterned, a lot too predictable, but fascinating nonetheless for what it shows of O'Neill's preoccupations and purposes before he found his true voice. It often sounds stilted and unreal but this is not over-acting by the cast so much as inexperience on the part of the playwright who couldn't, at this stage of his career, quite manage a speech that wasn't a mouthful. What shines through is his understanding of the American experience at just the time in his country's history when the coming of the railroads, the automobile, the industrial revolution — and the inherent restlessness of the American spirit — all came together to drive the previous satisfaction with life on the land into the background.

Far more successful, despite O'Neill's Pulitzer, both as a fully realized play and as a pointer to the future is Tennessee Williams' Spring Storm. Set in 1937 in a small town on the Mississippi, it is the harbinger of all the great Williams plays that will follow.

Here we have an empty-headed, half-educated Southern belle, rejoicing in the name of Heavenly Critchfield, who has made a bad choice. She has been sleeping with her childhood sweetheart, a local lout with no bloodlines or land who wants only to escape from the claustrophobia of the stifling Southern town and from Heavenly.

|

||

| Liz White and James Jordan in Spring Storm |

||

| photo by Robert Day |

In this very funny play are all the seeds of what is to come. Here are all the nuances of class and religion and money for which Williams' had such perfect pitch. Here too are the many ways snobbery hurts, from the clever girl whose mother takes in sewing to the rich boy who knows every gradation of social chatter but doesn't know how to talk to the girl he loves. Here are all his later interests from the fear of madness to what will eventually become Stanley Kowalski's sexual charisma. It's all here and decidedly not to be missed.

And if you don't like the play you can always stand on the terrace with a glass of wine and watch the boats go by towards Tower Bridge.

For more information about the National Theatre, click here.

(Ruth Leon is a London and New York City arts writer and critic whose work has been seen in Playbill magazine and other publications.)

*

Check out more of Playbill.com's international coverage, including London correspondent Mark Shenton's daily news reporting.