*

I've known Julie Taymor for over 20 years. She is a dear friend and on the board of directors of Theatre for a New Audience, which I founded. The media often reports that Julie was a director of experimental theatre before she staged The Lion King. But, between 1986 and 1996, years before The Lion King, I worked closely with Julie and her collaborator and partner Elliot Goldenthal on plays by Shakespeare and a 17th-century Italian fable, The Green Bird, by Carlo Gozzi, all of which were originally produced Off-Broadway. Julie loved these authors and staged their plays with boldness and a respect for their language and ideas.

When Julie recently invited me to see a preview of Spider-Man Turn Off the Dark, to be honest, I was nervous. Very nervous. Arriving at the Foxwoods Theatre, I felt like a juror who had been told so much beforehand about what was wrong with the production, that it was going to be impossible to be impartial.

Once Spider-Man began, however, it was unlike anything I had ever seen or felt. That's often the case with Julie's productions. Her theatricality engages the audience's imagination. Taymor is called a visual genius, but her imagination isn't only visual. It's visceral. She makes you feel what it's like to be something or someone else.

| |

|

|

| Jeffrey Horowitz |

| |

|

|

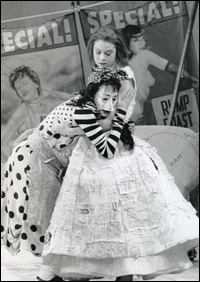

| A scene from The Green Bird |

The character of the King wore a mask that resembled former President Nixon and an exquisite actress painted her naked body for each performance to look like marble which magically became animated like Hermione at the end of Shakespeare's Winter's Tale. The audience cheered.

| |

|

|

| Helen Mirren in "The Tempest." | ||

| photo by Melinda Sue Gordon ©2010 Tempest Production, LLC |

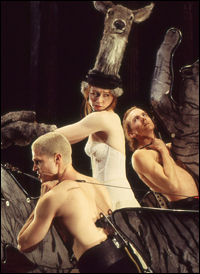

In 1994, I worked again with Julie when she directed Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus. Although some dismiss the play as the equivalent of a slasher flick, Julie saw it as a profound meditation on violence and why audiences enjoy it. In Titus, Shakespeare describes Rome as "a wilderness of tigers." Again, on a small Theatre for a New Audience budget in a 135-seat theatre, Taymor created terrifying sequences. I will never forget how she incorporated the head and tail of tiger puppets worn by two actors as they raped Lavinia, Titus' daughter, who Taymor placed on a pedestal in a Marilyn Monroe-like dress — the one that billowed in the famous "Seven Year Itch" photograph of Monroe. The production was acclaimed and extended. In 1999, Julie directed "Titus," a film starring Anthony Hopkins, Jessica Lange and Harry Lennix.

| |

|

|

| A scene from Titus Andronicus |

In media reports about Spider-Man, Taymor has been described as a perfectionist out of touch with concerns of budgets or the opinions of others. The person I know is a true collaborator who enjoys and wants the contributions of others and incorporates their contributions into her ultimate vision. She is also caring, hard-working and mindful of budgets. Furthermore, what's wrong with being a perfectionist or committed to a vision?

It is now reported that Spider-Man is undergoing rewrites and changes without Taymor. Julie Taymor is responsible for articulating her vision, and for me — and for what seemed like most of the audience who cheered when I saw Spider-Man — her vision was thrilling. It reminds me of a story about the artist Georgia O'Keeffe. In the 1930s, she was commissioned by Dole Pineapple Company to go to Hawaii and make two original paintings for Dole's advertising campaigns. As reported by Time, O'Keefe agreed, on condition that she could paint whatever she wanted. When she returned, O'Keeffe presented two canvasses: a vivid red canvas of crab's claw ginger and a lush green papaya tree. Papaya juice was Dole's rival. A tactful art director had a budding pineapple plant put aboard a plane and delivered to the O'Keeffe studio in Manhattan. "It's beautiful. I never knew that," exclaimed artist O'Keeffe. "It's made up of long green blades and the pineapple grows in the center of them." She promptly painted it. Dole got its pineapple but it wasn't literal and they used it in a magazine advertisement — not on the cans. Personally, I would buy cans of pineapple juice with a reproduction of an O'Keefe painting on its label. But, I'm not a corporation whose job it is to sell canned fruit.

Theatre for a New Audience is breaking ground this April on its first home, a 299-seat theatre in the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Cultural District. Construction will take two years. I invited Julie to direct the first production, but I have also asked that she work with us on whatever she likes as soon as she wants.

View highlights from Spider-Man Turn Off the Dark: