*

"He was bigger than life," three-time Emmy winner Bryan Cranston says. "Sometimes he was friendly, sometimes he was vicious. He would cajole, he would threaten, he would pressure, he would hug. He swung so wide on the spectrum of human emotions in order to accomplish what he felt needed to be done. It doesn't take much time for an actor to look at that and go wow, how wonderful and frightening to step in those shoes."

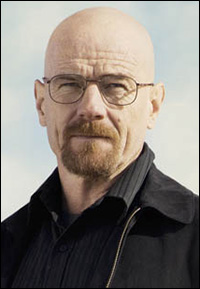

Cranston, 57, the much lauded star of television's highly praised series "Breaking Bad," is talking about Lyndon Baines Johnson, the 36th president of the United States, whom he will portray in September in All the Way, at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The playwright is Robert Schenkkan, 60, whose The Kentucky Cycle won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992. Schenkkan's play deals with Johnson's first year as president, from the moment he was sworn in on the airport tarmac in Dallas on November 22, 1963, after the assassination of John F. Kennedy until his election to his own full term in November 1964.

"It was a tumultuous whirlwind of a year," Cranston says. It's a new production of the work, which was first performed, without Cranston, in summer 2012 at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. The title comes from Johnson's campaign slogan, "All the Way With LBJ."

Schenkkan says that All the Way focuses on "the whole idea of the morality of power. We want our leaders to achieve, yet to what length are we willing to see them go to achieve those goals which we regard as worthy or even necessary?" Johnson, he says, "is the quintessential political figure to wrestle with that" – and it's "not an easy question."

LBJ, he says, "had an outsized effect on American public policy and American society and culture, both in some very, very good ways and some very, very terrible ways." His "legislative record on the domestic side is astounding – Medicare, Medicaid, Aid to Dependent Children, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, aid to education, his poverty programs, the 1964 and 1965 Civil Rights Acts: landmark pieces of legislation. The list goes on and on." But, he says, there's also the "catastrophe" and "tragedy" of Vietnam – "the lying over Vietnam started almost immediately."

|

||

| Cranston on "Breaking Bad." |

||

| AMC |

And he says he is glad to be back in a theatre dressing room. "I'm thrilled," he says. "The process of acting in film and television consists of bits and pieces. I relate it to an inverted funnel, where you're doing little pieces here, little bits there, and no rehearsal period, really. You're just kind of quickly putting it on its feet and trying to figure things out. And you shoot little bits and pieces and you put them in the small hole of the funnel, and it all comes together and comes out big later on, after sound effects and color correction and music. All these things get mixed in there. It becomes an event.

"For an actor, it's OK, there are always some gratifying things, but the process is not as gratifying as you'd like. It is what it is. You adapt to it."

But "what I love about theatre is that the funnel is right side up. It's wide and open and huge. And you're trying things – there are a lot of different avenues for you to go down, to experiment with. I keep telling myself whenever I do theatre, after a stretch of television, that it's OK not to know. I don't have to know right away. I can sit with the ambiguity of issues, and that's good. Let me contemplate, let me try things. And then you assemble all these thoughts and pieces and it shakes down into the funnel, and it comes out after you've done your work.

"I have a month of rehearsal in Boston. And that's just a part of it. I'm absorbing as much resource material as I can, listening to tapes and going back to the text." The cast of All the Way includes Brandon J. Dirden (The Piano Lesson Off-Broadway) as Martin Luther King Jr., Michael McKean (The Homecoming, Superior Donuts) as J. Edgar Hoover, and Reed Birney ("House of Cards") as Hubert Humphrey, Johnson's vice presidential candidate. Bill Rauch, the artistic director of Oregon Shakespeare, directs. The play has won the 2013 Steinberg/ATCA Best New Play Award for work done away from New York City in 2012. It is also a co-winner of the first Edward M. Kennedy Prize for Drama Inspired by American History.

All the Way, Cranston says, "gives the audience a glimpse into the sensibilities of its era," a decade that was among the most explosive in the history of America, one that included the assassinations of JFK, King and Robert F. Kennedy, the success of the civil rights movement, race riots across America and the Vietnam War.

"You can point to other times when there were big turning points, but there were also huge turning points in this era. It was 100 years after the Civil War, and civil rights in America were still mostly given lip service. Look at what Johnson was able to accomplish in a matter of months after taking office – pushing through and signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964," which made illegal many forms of discrimination against minorities and women. "It was extraordinary.

Johnson, who wielded enormous power as a senator from Texas and as the Senate majority leader, had always wanted to be president, Cranston says. But Johnson lost the Democratic nomination in 1960 to Kennedy and, after hesitating, agreed to run as the vice presidential candidate. It appeared to be a grievous mistake – there was no love lost between the men, and Johnson was isolated, essentially shoved into a corner with nothing to do and no power whatsoever.

|

||

| Lyndon B. Johnson |

And then suddenly, one horrible day, "he was thrust into the spotlight. But as much as he craved that position, he never thought it would come this way. And now it's here. And as the weeks went on, and he was getting more comfortable, he was also getting more uncomfortable. He was also starting to fret that 'I'm just the accidental president. I don't know if the American public truly loves me. They loved Kennedy. I was just along for the ride.'

"He was developing an absolute pressure cooker that 'I need to win the 1964 election on my own. I have to do that or I'll forever think that I will be in the history books as an accidental president, the man who became president only because of an assassination.'"

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 came at an ideal moment, Cranston says. "He was able to pull that off for a few reasons. A large part is that he knew all the players from Congress. He knew their strengths and weaknesses, what they wanted, and he gave them what they wanted so he could get what he needed. He knew how to play that game. He was a master politician."

Johnson also "realized that he was in a fortunate position politically – there was a honeymoon period, a mourning period, because the country was deeply saddened and shocked by what had happened. He knew that, and he used the words of John F. Kennedy, who wanted to get this done, and he said that these were Kennedy's policies, let's fulfill his hope." It "was sort of a perfect storm." Schenkkan, whose sequel, The Great Society, covering Johnson's second term, is scheduled for next year at the Oregon Festival and the Seattle Repertory Theatre, says that when Johnson took office, most of the country was "uncertain about what a Johnson president would mean. He had a very carefully calibrated political process of being all things to all people – conservative to the conservatives, liberal to the liberals, racist to the racists. What did Lyndon Johnson really want? – that was the question. And in what dramatic and exciting way he answers that, is the substance of the play."

It was, Schenkkan says, "a hinge point in American history – it's where everything changes. It is I believe where modern political America was created."

For Cranston, the final season of "Breaking Bad" begins Aug. 11, and he says he has mixed emotions about the series' end. "Actors, after a show and a production, you embrace, you cry, you rejoice, you promise to stay in touch, which we do and don't do. And then you move on. It's part of our DNA. I suppose you look back historically at the lives of actors, who were vagabonds, going from town to town with a hat on the ground. You perform, and hopefully a couple of shillings are thrown in there, and you get run out by the sheriff, and you go to the next town."

Cranston's next town may be New York, and Broadway – there have been reports that All the Way may wind up on the Great White Way.

"We're taking it one step at a time," he says. "Sure, I'd love an opportunity to do that. If we're well received and I do my job, there may be a life after A.R.T. Right now, we're really focusing on presenting our show there, and whatever happens after that, happens."

He is, he says, happy just where he is right now. "To be able to allow myself to be myopic at this point and just focus on this project is a luxury. Because usually you're putting out all kinds of feelers – what else is on after this job is done? What's developing? I've just stopped all that. I don't want to hear it, to be involved in any of that right now. After working hard for 13-14 years on television, I want to be able to step back, slow it down and control the next chapter of my life."