*

The tendency is to ask the question right off: "Do you think people as ethnically and culturally far-flung as these four could ever get together for a meal?"

Ayad Akhtar, who set places for a pretty extreme quartet in his play, Disgraced, likes to let his nitpickers load up the unlikeliness of it all before he lowers the boom. "Well, they did," he says with the calculated cool of someone who has that question covered. "The play was based on an actual dinner party at my home in Harlem in 2006. The party didn't end quite as badly in real life as it does in the play."

It obviously didn't end particularly well, either. He and his "now-ex-wife" had two friends over — one European, one Jewish — and somebody said, "Islam: Discuss."

"I don't think any of them knew I was Muslim," Akhtar recalls, "because that night I felt like something very important shifted between me and my now-ex-wife, just in terms of perception and the ways that articulating certain aspects of Muslim identity can make people scared."

"It was a subtle thing that happened that night, but I remember thinking, 'This is an interesting premise for a play, where conversation at a dinner party ends up irrevocably changing everyone's relationship, professionally and personally.'"

| |

|

|

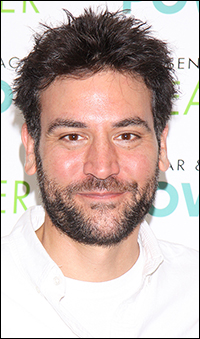

| Josh Radnor | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Amir's white, liberal wife, Emily (Gretchen Mol), is more the Islam expert, an artist specializing in Islamic imagery. Their party guests are Jory (Karen Pittman), Amir's African-American colleague, and her husband Isaac (Josh Radnor), a Jewish art curator. The party starts out a civilized soirée and, with the influx of ideas and opinions, turns into an explosive guess-who's-coming-out dinner.

"The current of that evening ran through me for a couple of years, I think, as the conceit for a much larger dramatic exploration of this — using that conceit as a surgical scalpel on post-9/11 cultural and identity politics," contends the 43-year-old New York–born Milwaukee-bred son of Pakistani parents. "It didn't really bubble up until 2009, and I started writing it, finishing my first draft in 2010. It took that long to germinate as an idea in me. Sometimes it takes a long time for it to swim around before it comes back up."

The sound of intelligent people conversing, arguing and articulating their angst is a theatrical rarity that works a mesmerizing hold on the audience. "For many of us, the texture of lived life is filled with ideas. It's not just about what we can't say or what we don't say. It's about what we think and what we try to say to other people.

"I want to engage an audience intellectually, emotionally and narratively, open up a field of possible meanings and reflections on the world that we're living in — but that does not dictate in any way how people feel about it. I want them to be delivered over to their own sense of the world we're living. One of the important things about this play is that it releases a kind of trouble into the audience that they can't let go of — and, because they can't let that go, they keep asking questions about it."

This same understanding (and sometime misunderstanding) of what it means to be Muslim in America is a narrative that is carried out in Akhtar's other work. His 2012 novel, "American Dervish," centers on a Pakistani-American boy growing up in Milwaukee. His play, The Who and the What, which wrapped up a run last month at Lincoln Center Theater's Claire Tow Theater (also where Disgraced debuted), follows a Pakistani immigrant struggling to pass on his devout Islamic faith to his two assimilated grown daughters. Akhtar's upcoming play, The Invisible Hand, about an American hostage in Pakistan, will make its debut this December at New York Theatre Workshop.

And while all of Akhtar's written work does a good job of stirring up discussion about the lives of Muslim-Americans today, Akhtar says he doesn't set out to give definitive answers to multifaceted questions. "I don't think the complex geopolitics and identity politics and ethnic politics that are at play in the world today can be solved in a play," says Akhtar. "I don't think you can comment in any comprehensive way on them in a play, but you can depict people grappling with those questions.

"The Great American Story is rupture and renewal — rupture from the Old World, renewal in the New World of the self. Even so many generations in, Americans are still doing that. They are rupturing from their primary families, moving to other coasts, forming surrogate families and surrogate communities. That process of renewal of the self through rupture is the American story, in many ways."

For Akhtar's Disgraced protagonist, the dangers of denying his racial and religious inheritance are writ large. "Amir is not allowed to do that. He's not allowed to because — in a post-9/11 landscape — his being Muslim, even if it's only by origin, marks him. In a way the play is also a meditation of the failure of the American dream for this particular individual. He's got it all, and, yet, somehow it's predicated on a lie that he will not be allowed to continue to live. If he could've, he would've."