*

What is the biggest challenge of staging a cult hit like Les Miz? Especially with it currently being revived on Broadway? Does it matter?

Liesl Tommy: The biggest challenge is managing the pressure of expectation. Directing Les Miz is a bit like directing a film of a comic book or graphic novel with a rabid fan base. Every casting choice and costume choice comes with a clash in the hearts and minds of the fans…”It’s not supposed to be like that…” – knowing this was on people’s minds and pushing forward with our vision regardless was quite a challenge. The brilliant costume designer Jacob Climer and I had a wonderful process grappling with “expectation” then discarding it and trusting our sense of storytelling.

It being on Broadway didn’t impact me because, in a way, it gave me license to do something very different. If people want to see the beloved traditional version, they can get it on Broadway or the tour. My job was to explore my personal connection to it and to re-imagine it.

What is your personal connection to the story?

LT: Well, this was one of the books I read at a very young age and it was an astounding experience. My favorite European writers as a child were Forster, Hugo, Dickens, Austen and Hardy. So, I have very vivid memories of the book, of the images I had in my mind as I read it.

I am also a child of a revolution, being from South Africa during the Apartheid era, which was marked by many decades of brutally suppressed student uprisings, so I am deeply connected to the themes of revolution in this story. I find them profoundly moving and familiar. I also have lived and worked in environments of abject poverty. I feel one of the reasons people are so responsive to this particular production is because it is saturated with my personal connections to the story. I think they feel it’s coming from an authentic place.

Whose story is Les Misérables telling?

LT: The musical is telling the story of Jean Valjean’s journey to redemption and the story of a student uprising. But it’s also a story about spirituality and the different ways to live a life of faith. And it’s a story about what it means to live in a brutal and indifferent society and still have compassion for your fellow human, to take a stand, at great risk to yourself, to try to eradicate other people’s suffering. And about loving another person with everything in you. So many humanistic themes, it’s a privilege to stage.

| |

|

|

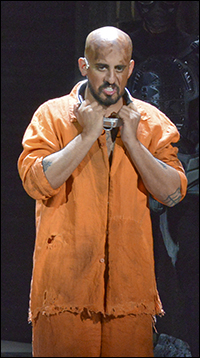

| Nehal Joshi as Valjean | ||

| Photo by Karen Almond |

LT: Well, I think there’s a lot of those three words in this show and when the production shots come out, that’ll be clear! Firstly, the cast is extremely diverse: lots of casting against type.

Secondly, I always interrogate my work and my script by first asking myself what makes a thing 21st century art. That is my mandate. Always.

For example, when I thought about each scene, I obsessed about what the images were that would make the storytelling the most immediate and visceral for the audience. Therefore, “Look Down” or the prison sequence doesn’t look like what people expect. The very first image of the show is a prisoner in an orange jumpsuit getting violently beaten by prison guards in riot gear. John Coyne’s brilliant set looks kind of like a maximum security prison then and it’s brutal. It’s an intense way to start the show, but you feel the audience snap to attention and the energy in the room gets electric, like “Oh sh*t! this show is not playing around!"

Another example is “One Day More.” When I first started pre-production, I had one image that I showed all the designers and all the staff at DTC, and that was a Youtube video of a political demonstration in a township in South Africa. The demonstrators are all singing and dancing the Toyi-toyi, which is what was typically done in SA [South Africa] during such demonstrations. I didn’t know how I would use this in the show, but I knew I wanted to communicate this urgency and energy. Christopher Windom and I ended up using our interpretation of it in “One Day More,” which has become a moment when people start screaming and applauding before the lights are even out. It’s pretty thrilling to watch the audience watch this show.

What was it like in the room together? Collaborative, "traditional"? How much say did the actors have in the final product?

LT: Well, it was pretty wonderful in the room. I think the actors were constantly surprised because I approached the process like I was doing a new play. We spent the first week on table work with very little time singing. That was a head trip for the real musical theatre people I am sure, but they were super game. I just wanted to make sure every single person down to the littlest kid in the cast understood the story we were telling. Every nuance of every arc, every relationship, every political insight, every element of the story was inspected and discussed. This, for me, is the basis of directing: the discipline of rigorous text analysis, the kind of dramaturgy that brings forth the freedom of clarity, which leads to deeply passionate performances, and it’s my religion. I like to think of myself as a very collaborative director who gives artists a lot of space to create, but I also have a vision and I know exactly what I want. The trick is to get everyone on board to your vision and then they start creating in that vein. The actor playing Jean Valjean was a gift to me. Nehal Joshi is a transcendent actor: endlessly inventive and one of the most soulful performers I’ve ever encountered, and he got what the game plan was and lead the charge. He was the model lead. But, as we all know, the bulk of my job is casting it right, and with the help of Joel Farrell at DTC and Patrick Goodwin at Telsey + Company, we got an insanely talented group of performers.

| |

|

|

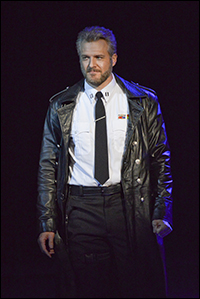

| Edward Watts as Javert | ||

| Photo by Karen Almond |

LT: Well, never. Not the show or the film.

You recently directed Appropriate at the Signature Theatre, a new play, for which you won an Obie award and the Lillian Hellman Award for directing. What are the differences in working with a new play and working with something that seems to be set in stone to a current audience – that has a precedent?

LT: I work on new plays and classics in the exact same way, as I mentioned above. Rigorous table work and text analysis always is the basis of my process. The biggest difference though is with classics I don’t feel the pressure that ushering in a premiere brings. You just want the absolute best for the writer and this creation they have labored over, and that is a kind of labor that is unlike any other labor. So the pressure I put on myself for the future of a new play is way more intense.

Do you prefer plays, new plays, musicals?

LT: I love it all, but the more theatrical the better for me. And theatrical can be about music and movement, or about pushing form in a straight play, or about really thrilling muscular language. I have been lucky to work with really thrilling new writers as well as classics like Hamlet at Cal Shakes, or classic modern plays and Les Miz recently as well.

What's it like working regionally versus working in NYC? Pros and cons?

LT: Well, that’s a naughty question!

Regionally pays better than Off-Broadway – unless we’re working commercially – as we all know, and better artist pay is something for which I am always advocating. I also get to work with bigger budgets, bigger houses and bigger stages at many of the LORT theatres. But one gets to premiere cool plays Off-Broadway, so both have their plusses.

| |

|

|

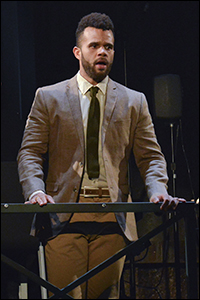

| Justin Keyes as Marius | ||

| Photo by Karen Almond |

LT: There are many places I have worked at repeatedly over the years, and that is due to the wonderful relationships I have with the artistic directors at those theatres. It’s so important to feel like your voice is heard and understood and the offers from those AD’s usually reflect that. I was recently lucky enough to win the Alan Schneider Award for Directing from TCG [Theatre Communications Group] and in my speech I spoke at length about this topic.

Kevin Moriarty is a very special AD because I met him when I was an acting student at Trinity Rep Conservatory, now the Brown/Trinity MFA Programs. He directed me in a play and I just respect his work so much. We stayed in touch, and when I developed my first big project, The Good Negro by Tracey Scott Wilson, he and Oskar Eustis at the Public co-produced the world premiere. They, along with Philip Himberg at the Sundance Institute, essentially helped launch my professional career.

In terms of Les Miz at DTC, Kevin saw my production of Party People at OSF, a multimedia musical about the Black Panthers, and he loved the energy of that piece. Thankfully, he made the connection between what I was doing with that piece to what I could do with Les Misérables and brought me on board. He also made it clear that I could give my imagination free reign to interpret it. So I did. This is the kind of artistic director you pray runs a building.

Any advice for new directors?

LT: People always ask me this question. It’s so hard. Building a directing career is very, very difficult. Because people fear taking risks on unknown directors, but know what your strengths are and what part of theatre you have a special insight into – for me it was political theatre – and pursue that relentlessly, obsessively and make relationships with people who care about those same things. And hone your craft! Get training! Don’t be a dilettante!

| |

|

|

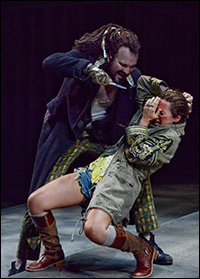

| Steven Michael Walters as Thenardier and Elizabeth Judd as Eponine | ||

| Photo by Karen Almond |

LT: I was an actor and I love acting and actors. Firstly, don’t be a nutter and don’t be a jerk. There are millions of talented people out there, so many that I don’t need to put up with selfish crazies. Try to be healthy so your talent can shine through. Try to be kind and generous so we want you in the room.

I went through a period where I shunned auditions and cast from just having chats with people. I would look into their eyes as they talked and watch their body language and listen to their stories and really try to see them. I loved that process. I did some wonderful casting that way.

With traditional casting the same applies. I respond to the actors who come in and through their audition really let me see them; who understand how to reveal their heart and soul through their audition sides, who make smart and bold choices but also understand the text. But for me, I want always to see complexity and humanity. The people who know how to reveal that are who I want in my room.

What’s up for you next?

LT: The 2014-15 season is all musicals. I’m super thrilled to be working with these brilliant collaborators! Les Misérables at DTC, obviously. Party People by Universes at Berkeley Rep and then eventually NYC. Kid Victory, music by John Kander, book and Lyrics by Greg Pierce, a co-pro with the Vineyard Theater and the Signature Theatre, and a world premiere, Melancholy Play written by Sarah Ruhl with music by Todd Almond at Trinity Repertory Company, and continued work at the Sundance Institute (Program Associate) and Berkeley Rep (associate director) developing pretty awesome new projects.