*

An explosion of spectacle dazzled Broadway this season. Special effects seemed to proliferate everywhere, ranging from simple old standbys (smoke billowing across the stage in La Bête and Wonderland, actors in the air in Priscilla Queen of the Desert, Brief Encounter, and How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying) to puppetry (The Pee-wee Herman Show, Brief Encounter, War Horse) to stagecraft that combined set and lighting (Priscilla, Elf). The effects weren't necessarily unfamiliar — after all, Mary Poppins has flying actors; The Lion King has puppetry; and Billy Elliot has both. But directors and designers infused their productions with unusual levels of stage magic during this season.

Desert Queen

One of the most notable eye-openers — it is, after all, the title of the show — was the 40-foot bus designed by David Thomson for Priscilla Queen of the Desert to carry its trio of stars to the Australian outback. From Australia to London to New York the design evolved, tailored to stage size, the logistics of scene changes, and Thomson's own instinct.

"I figured it should start out looking 'real' and be able to reveal its interior and change color in front of the audience," says the designer. "At various meetings with our production manager and tech people, we looked at how the bus might change color once it had graffiti sprayed on one side at its first scheduled stop." On stage, the vehicle turns completely around and undergoes a paint job to erase the graffiti. "I wanted Priscilla — as the leading lady — to be able to have costume changes and get to have fun in the outback herself," says Thomson, "like the bubble bath she has during 'Girls Just Wanna Have Fun.'" He considered panels that could be added or taken away, but hit on the solution while on a bus in Sydney — "just watching the lights flick by," he says. "It suddenly dawned on me that we just had to do the color change with lights — not from outside sources but from within."

Buy the 2011 Tony Awards Playbill |

The lighting effects occupied a good deal of his attention — and still do, though the production has opened. "With all of the set electrics, I wanted to use as much as I could from different eras — simple ropelite and Christmas bud lights right through to the most sophisticated LEDs available, that we could afford," he says. "I still want to add three colored fluoro tubes to the Coober Pedy Drive-In piece and some odds and ends, red bulbs, to the Hotel Woop Woop sign — we couldn't fit them in in New York, as the stage is so shallow."

The bus's most startling feature was, of course, the giant Swarovski-crystal-bedecked shoe. "The shoe moment was a very iconic sequence in the film," says Thomson, "and we somehow had to make it happen. Garry McQuinn, our producer, wanted the shoe to fly out into and over the audience, but we did compromise and just had it pop out a few rows." But with Nick Adams as Felicia, lip-synching an Italian aria on the shoe, the moment became a highlight of the show as well.

|

||

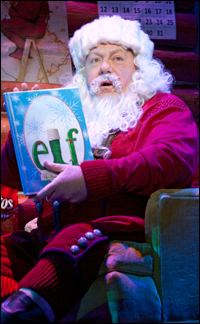

| George Wendt in Elf |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

A similarly iconic set piece — Santa's seven-foot long, 600-pound sleigh — was created by designer David Rockwell for only 20 seconds of flying time in Elf, the Christmastime musical. The result was a product of collaboration among director, designer and writers. "In early conversations with [director] Casey Nicholaw," Rockwell says, "we talked about projections, miniatures, and the joy of actually seeing George Wendt [as Santa Claus] flying in the sleigh."

But what about Dasher and Dancer, et al.? "So much of the show was predicated on the belief in Santa that we proposed a sleigh that didn't have reindeer — more of a sculpted sleigh," says the designer. "The writers liked idea of sleigh stripped of its reindeer by PETA activities, so it was powered only by the spirit of Christmas." The result had workable headlights, silver hood ornaments, and an illuminated red nose for the sculpted head of a reindeer at the front.

The magic of flight was created mechanically, of course, but with an extra dose of ingenuity. "The back of the sleigh was attached to a counterweighted hydraulic telescoping arm," explains Rockwell. "It acts like a lever that lifts the sleigh up 14 feet in the air at the same time that it's moving six feet toward the audience. So that, in effect, had the sleigh taking off while it was moving toward the audience with Santa in it. We also put the sleigh at a 90-degree angle off to the side from center stage, so it was moving up and out, and moving at a diagonal.

"Typically," he explains, "when an actor is flown like that and raised above the stage, it's done with cables, and it moves left and right. We wanted the action to feel more emotional, so moving toward the audience on this arm was the way we pursued it." The hydraulic arm was encased in a black velvet sleeve, and, as the sleigh moved downstage, the headlights — Natasha Katz was the lighting designer — beaming at the audience helped disguise the contrivance. In fact, "treading the boards" has rarely meant "feet off the ground" so frequently as this season. Actors took to the air — with controversial, ground-breaking (as it were) stunts in Spider-Man Turn Off the Dark, which delayed its opening. They flew upward on wires in Brief Encounter, as well as the long-running Billy Elliot, and they descended on them in How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying and Priscilla. In How to Succeed the descent was practical: the characters on wires are washing windows.

|

||

| Joanna Lumley in La Bête |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

"I thought I could improve it if I could emphasize the different 'chapters' of the piece," says Warchus. "I identified five major chapters or 'acts' in the journey of the play and set about giving each new chapter a strong start so that there would be an injection of energy and we would feel a clear temperature change in the story, like a new weather system blowing in.

"I imagined the arrival of the Princess, her unassailable power and force, as being like a tornado blowing into the room and causing chaos," he explains. "I drew a sketch on the back of an envelope of her entering in a horizontal blast of wind, which would almost cover the whole width of the stage, and asked for this blast of wind to be gold and sparkling (like her costume) like a glitter tornado." The actual effect was sourced to technical supervisor Gene O'Donovan, adds lighting designer Hugh Vanstone, and was created by using "a custom-made, large directional electric fan and glitter, with extremely bright golden side light."

Pee-Wee's Magic

Vanstone's lighting was a bravura moment. But puppeteer Basil Twist used lighting not to call attention to anything, but to hide the effects he created for The Pee-wee Herman Show, particularly when Pee-wee's dream of flying comes true. Long before Pee-wee's 1980s TV show, Paul Reubens had played the character for the Groundlings, a comedy club act in Los Angeles. Back then, it was a low-tech, charming moment. "There was a puppet face and a puppet body," says Twist. "He would just stand there, and the audience would get the idea." For the production at the Stephen Sondheim Theatre, Twist needed to upgrade the flying effect, but Reubens balked at being lifted by wires. "They actually tried that, and he hated it," says Twist. Instead, he suggested using a crane to move the star. "We found a small one that raised him about nine feet in the air," says Twist. "Then we completely covered that crane and everything we didn't want seen with black velvet." The lighting was crucial to pull it off, however.

Reubens wore a backpack that had the puppet body of the character extending behind it. Using a combination of ultraviolet light and special paint, Twist hid the operational elements from the naked eye. "That black-light effect renders everything else invisible," he says. "Otherwise, you would perceive that stuff on stage. His face needed to be isolated, and the light doesn't hit other things on stage."

To further the effect and illuminate Pee-wee's face, Twist employed a different style of lighting, on poles that extended in front of Reubens. "They were little pin spots that lit just his face," says Twist. "That way he could turn left or right, but those little pin spots would always stay on his face and wouldn't light up the crane." The result is that when Pee-wee first appears, one has the impression that the actor is merely standing on stage with the puppet body behind him. "But then," says Twist, "he goes up in the air. It was cool."

Twist's favorite effect was "a film idea that was transferred to stage," he says. Near the end of Pee-wee's show, a variety of big, monster-like eyes moves across a darkened stage. "They're little, battery-powered light boxes that have moving pupils and blinking eyeballs," says Twist. "Puppeteers in black were moving about in space with these little light boxes." Amid a season of complicated, risky, breathtaking effects, this one, says Twist, "was actually pretty easy."

*

Edward Karam is a freelance arts writer and critic based in New York City.

This article appears in the Playbill for the 2011 Tony Awards, June 12, at the Beacon Theatre on Manhattan's Upper West Side.