I heartily salute Masterworks Broadway for their diligent and admirable program of digging long-lost musical theatre albums out of dusty archives and bringing them back where they belong. That said, I must confess that their two most recent offerings offer little for me. But that's not to suggest that you won't find them interesting, so read on.

"A Little Night Music"

Much has been said of the ill-guided 1978 motion picture version of Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler's "A Little Night Music." This was certainly an inauspicious time for esoteric movie musicals. Hal Prince, who directed and produced the 1973 musical, helmed the film. Wisely, he brought three of the five leads from the Broadway cast. He also allowed Jonathan Tunick to expand his luscious original orchestrations, which earned the Tony/Emmy/Grammy winner his Oscar. Prince also gave Tunick a bit of screen time, playing — what else? — a musical conductor.

Otherwise, though, "Night Music" was a mess, exemplified by the casting of Elizabeth Taylor in the leading role. A big movie star, yes; but not precisely right for the enchanting Desirée Armfeldt. She was placed opposite two leading men who — while virtually without film experience — knew their roles could only serve to make Taylor look more out of place, especially with Len Cariou (as Frederick) and Laurence Guittard (as Carl-Magnus) singing up a storm. Taylor didn't quite sing up a storm; the new liner notes, by Peter E. Jones, tell us that her rendition of "Send in the Clowns" was snipped together from numerous takes, "fixed" by a second singer, and further helped by a final dubbing section by another whom, we are told, "remains secret to this day." Hermione Gingold's Mme. Armfeldt from Broadway was also present, although her big solo ("Liaisons") was not used in the film. Other significant deletions included "Remember," "In Praise of Women" and "The Miller's Son."

The one extra-positive element in the film is the Charlotte of Diana Rigg. Best known at the time for her stint as Emma Peel in TV's "The Avengers" and her role in the 1969 James Bond film "On Her Majesty's Secret Service," Rigg had earlier started her career with the Royal Shakespeare Company. She returned to the stage in the early '70s with Abelard and Heloise and Tom Stoppard's Jumpers. In "Night Music," she not only acts her role delectably but sings jolly well — so much so that when Sondheim's Follies finally made it to the West End in 1987, Rigg shone as the icy Phyllis Stone. Added tracks on the new "Night Music" include an expanded version of Rigg's "Every Day a Little Death," containing the carriage ride section not heard on the original LP.

The soundtrack album, which Masterworks has now brought us, is checkered. Any recording of Sondheim has natural interest, certainly, and the expanded orchestrations sound very nice (although those of us who know the score might wince every time an interior section of precious Sondheim is cut). The highlight is a new song written for the film, "The Glamorous Life." The song in the show of this title is a highly enjoyable group number, featuring Desirée as she packs up the luggage. The song in the film is a solo for the daughter Fredericka, in which she talks about her mother's glamorous (?) life. Both songs, let me say, are personal favorites; they brilliantly accomplish what they set out to accomplish, with enchanting music and delicious lyrics, and I couldn't possibly favor one over the other. The role in the film was played by Chloe Franks, but dubbed by Elaine Tomlinson. (Tomlinson also did some dubbing for Taylor and Lesley-Ann Down, who played the child-wife Anne.)

Where the recording sparkles — for me anyway — is whenever Cariou starts to sing. We know what he's going to sing and how he's going to sound, yes. But his performances of "Now" and "You Must Meet My Wife" are alive, fresh, and most welcome to us fans of the original Broadway cast album. The same can be said for "It Would Have Been Wonderful," his duet with Guittard. As for Cariou, the "Night Music" film marked the end of a stage of his career. Next up: Sondheim and Prince's Sweeney Todd.

| |

|

|

| Cover art |

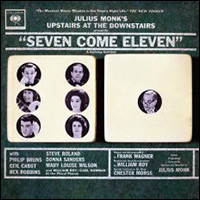

A fellow named Julius Monk dominated the Manhattan cabaret world from 1956-68, devising and producing a series of sophisticated late-night revues. Four Below led the parade, followed by Take Five, Demi-Dozen, Pieces of Eight, Dressed to the Nines and more. Most of these revues were recorded, albeit by small labels. His Fall 1961 offering, Seven Come Eleven, came from Columbia, and thus is the first of the Monk revues to come to CD.

According to the liner notes, Seven Come Eleven was received as the height of sophistication. Maybe so, but I am somewhat stunned by how decidedly unfunny I find it. Topical comedy dates quickly, yes, and perhaps that's part of the problem. But the other Monk revues I listened to, back in LP days, were far sharper than what we get here. What's more, much of the material in non-Monk topical revues — like the songs in the New Faces series and the comedy in "An Evening With Nichols & May" and "Beyond the Fringe" — holds up quite well today.

Seven Come Eleven includes a song about how unlivable modern New York is, with all those subway breakdowns; a song about new First Lady Jackie Kennedy; a song where the actors comport themselves like school kids, learning about big city scandals; a song about Henry Miller's scandalous novel "Tropic of Cancer," which had until 1961 been banned in the U.S.; a song about grand old hotels being torn down; a Pinafore take-off about a fellow who just loves to sew pinafores; a hymn about the newly-formed Peace Corps; a song about planes hijacked to Cuba; and a song about the John Birch Society.

The live audience at Monk's Upstairs at the Downstairs seems to be having a grand old time, but I don't find any of it funny — that is, except the line deliveries from Mary Louise Wilson. (Monk's revues included many young talents who went on to better things, but Wilson is the only discovery here.) The only out-of-the ordinary track is the one outright showtune in the revue, "I've Found Him." This was indeed a showtune, from All in Love, the Jack Urbont-Bruce Geller musicalization of The Rivals that opened Off-Broadway a month after Seven Come Eleven. (All in Love has a bright and enjoyable cast album on the Mercury label, which would please many listeners if only someone decided reissue it. And yes, lyricist Geller is the same guy who went to Hollywood and devised the hit TV series "Mission: Impossible." This is why the background music on "Mission: Impossible" sometimes intersperses themes from All in Love.) There are also two not-too-funny comedy sketches, one of them a take-off on Tennessee Williams.

(Steven Suskin is author of "Show Tunes" as well as “The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations,” “Second Act Trouble,” the "Broadway Yearbook" series and the “Opening Night on Broadway” books. He also writes the Aisle View blog at The Huffington Post. He can be reached at [email protected].)