*

How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying [Decca Broadway B0015645]

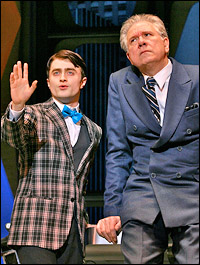

I warmly praised the Daniel Radcliffe revival of How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying when it opened in March, calling the enterprise "bright and irrepressible" and opining that the star "handily demonstrates how to succeed in musical comedy."

Does this mean that I find it comparable to the original production, which I saw when I was nine and remains one of three musicals which more or less formed my theatrical tastes? No, not at all; this new How to Succeed is not as startlingly good as the show that opened on 46th Street in 1961. But I don't think that's a fair or proper test for a revival to be submitted to, unless you're reviving a show that was first produced less than ten years back. I choose to consider revivals from the vantage point of a present-day theatregoer, sitting there tomorrow night or next month.

The curtain goes up and there is the Frank Loesser-Abe Burrows How to Succeed. Does the current production, directed and choreographed by Rob Ashford, present the material in such a way that it works? that the authors' intentions come through to today's audience? that the majority of theatregoers filing into the Hirschfeld, with little or no prior knowledge of the show, will respond by saying — in a word — "Yes!"?

I myself said "yes!" to this How to Succeed. The deftly witty musical that the boys contrived back in 1961, which received seven Tonys and a Pulitzer Prize, comes through. Abe's satirical jokebook plays like a marvel, garnering continuous and deserved laughter from the audience. Frank's score, every moment of it, is a delight. Loesser, who loved nothing more than writing big, booming songs, took the job with misgivings; he instantly realized that the needs of the show would restrict him to carefully-crafted comic novelty songs. No room for any Loesser ballads that might show up on the Hit Parade and the charts — back at a time when show tunes did, indeed, still show up on the charts.

|

||

| Daniel Radcliffe and John Larroquette |

||

| photo by Ari Mintz |

This was, not coincidentally, my precise reaction to the 2009 revival of Guys and Dolls, from the same director as the 1995 How to Succeed. And also not coincidentally, I had something of the same reaction to the 2010 revival of Promises, Promises, from the director/choreographer and producers of this present How to Succeed — which was, at least, far better than the 1995 How to Succeed or the 2009 revival of Guys and Dolls.

The present How to Succeed, though, heartily succeeds on stage. As good as the original, with an exceptional cast, wonderfully bright Fosse choreography of a sort we haven't seen since the master's style turned dark with Pippin (and the film version of Cabaret), and whimsical scenery seemingly drawn with cartoonist's ink? No. But does the revival present the authors' work in a way that should make your average theatregoer, who is not necessarily a musical theatre historian, respond enthusiastically? Yes, in my opinion.

Which puts me at something of a loss in discussing the original cast recording of this new How to Succeed. The revival works in the theatre as described, and there is no sense in asking someone to compare what you can see on stage today with a production that closed in March 1965. (You can get a sense of the original production from the 1967 motion picture, but only a sense.) The cast album is different, though; you can very easily compare today's recording with that of yesteryear.

Now let us readily agree that a stage musical is a living thing; just because a group of people — including the authors — decided to do it one way back then, doesn't necessarily mean that's how it needs to be done now. South Pacific, we saw at Lincoln Center in 2008, benefited from sticking closely to the original; the 1998 Cabaret, however, benefited significantly from changes in material, structure and viewpoint made by Sam Mendes and Rob Marshall.

|

||

| Rose Hemingway |

||

| photo by Ari Mintz |

This was the course taken for the 2009 Roundabout revival of Bye, Bye, Birdie — a prime example of a revival that somehow subverted every good idea that the creators had when they wrote the thing. Jonathan Tunick's reduced orchestration of Birdie, paradoxically, retained the colors and magic of the original; the one praiseworthy element of that revival, as it turned out.

The alternative is to start from scratch, allowing the present-day creative staff to have the show arranged and orchestrated to their own taste (in the same way that Loesser, Burrows, and Fosse were able to get precisely what they wanted). Should the choreographer intend to throw out the old dance arrangements and fashion new ones, you'll naturally need a significant amount of new orchestrations — even if you otherwise closely follow the originals.

And so, presumably, the decision was made to have Doug Besterman reorchestrate the show, giving it a brand new sound. The producers, in their liner notes, go so far as to spend five full paragraphs discussing the musical approach to the new Succeed. To sum it up, they decided "to think in terms of a muscular jazz ensemble rather than a symphonic sound"; found inspiration in the work of 1950s arranger Marty Paich and his Dek-tette recordings; purposely gave World Wide Wickets the musical flavor of Spacely Sprockets in Hanna-Barbera land, where George Jetson used to work (and no, I'm not making this up); and added the sound of Esquivel and his "Space Age Bachelor Pad Music," along with Henry Mancini and Martin Denny's faux Polynesian "Exotica."

Me, I prefer the sound of Robert Ginzler and Elliot Lawrence, who worked to Frank's specifications and came up with a dazzling set of orchestrations that perfectly complemented not only the score but the entire production. It was Ginzler who put that typewriter in the pit for "A Secretary Is Not a Toy," plus the off-pitch kazoos to fill in for electric shavers in "I Believe in You" — two whimsical touches which Loesser seemed to love, and which are gone.

Yes, I find the revival to be perfectly enjoyable, even with these new orchestrations; most audience members are oblivious to this sort of thing, and why carp if the show succeeds? But that's in the theatre. Sit that same audience member down with the two cast albums — which is fair game — and the difference is startlingly apparent. You need only compare the overtures; Ginzler's takes off like a rocket, Besterman's doesn't.

Before moving on, let's have a word for Daniel Radcliffe. The fellow is absolutely fine. No, he's not Bobby Morse; but Bobby Morse isn't likely to play the role today. (I would make another trip to the Hirschfeld immediately if Morse were to step into J.B. Biggley's shoes. Or even if he came in to play the supporting twin roles of Twimble and Womper.) Keep in mind that Morse had a great advantage, going in; Burrows, who had worked with him previously, crafted Bobby's scenes to specifically fit his talents — which is why those asides, sheepish grins, et al came so naturally.

Radcliffe didn't walk into the rehearsal room with the meticulously developed stage presence of Morse, but hey — he's only 21. When Morse was 21, he was struggling to get work on soap operas; Radcliffe, already, has starred in the West End and on Broadway in Equus, and also made some movies. Radcliffe maybe does not measure up to Morse in the role. The question is, though: does his performance bring the full value of the role and the show to present-day theatregoers? I say that Mr. Radcliffe pulls it off exceedingly well. Let us hope that now that he has given musical comedy a chance, he will feel at home on Broadway and return to us periodically.

|

There is less to be said about the original cast album of Catch Me If You Can. The new musical from the songwriters, director, choreographer and producer of the delightful Hairspray, doesn't begin to match up to their earlier effort. Much of the problem can be traced to the 1960s variety show format through which the tale — the autobiography of conman Frank Abagnale, Jr., made popular by the 2002 Leonardo DiCaprio-Tom Hanks film from Steven Spielberg — is told. The talented songwriters Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman seem to be nostalgic for those 60s variety shows, which is well and good for them. But if you stake your show on a genre that doesn't charm your audiences, you are deflating air from your tires and enthusiasm from your customers. Catch has attracted some strong fans, but seemingly not in sufficient numbers. And mind you, Catch nevertheless offers significant entertainment value.

But those variety numbers fall flat. And as you start to listen to the cast album, you are hit by one after another: "Live in Living Color," "The Pinstripes Are All They See," "Jet Set," "Doctor's Orders." There are, naturally, some delights to be found. The strongest — at least if you've seen the show — is "Don't Break the Rules," in which Norbert Leo Butz gives one of the most memorable eccentric dancing exhibitions since Michael Jeter in Grand Hotel. Which serves to accentuate one of the main problems of the show.

|

||

| Aaron Tveit |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

Dirty Rotten Scoundrels — directed and choreographed, not coincidentally, by the director and choreographer of Catch Me If You Can — was written in such a way that the actor playing the role of Freddy needed to overwhelm us with talent and charm. That need is even greater in Catch, but unfulfilled. (This problem might be not in the acting but the writing; Mr. Tveit was reportedly more successful in this respect during the Seattle tryout, before rewrites were instituted.)

"Don't Break the Rules" is the best number in the first act, and it is very much unlike most of the rest of the show. "(Our) Family Tree," which comes late in the second, is another rambunctiously enjoyable number, full of magnolias and fresh julep. (This song, in itself, demonstrates that composer Shaiman is perfect for musical comedy.) Kerry Butler, who was so memorably enjoyable as Penny Pingleton in Hairspray, comes on at almost the last minute with her solo, "Fly, Fly Away." Highly effective, but — like the Butz solo — it seems to fall outside the rest of the score. Catch Me If You Can is graced with one of the biggest, and one of the finest, Broadway orchestras of the past season. The producers seem to have consciously decided to give us a big band sound from a big band — a decision which pays off, big. The music of Catch — with orchestrations by Shaiman and Larry Blank, and music direction by John McDaniel — sounds mightily impressive at the Neil Simon, and on the cast album. But that sound, and the ministrations of Mr. Butz, aren't nearly enough to make this likable show soar like the jet in its logo.

*

|

The recent batch is headed by The Girl in Pink Tights. This 1954 musical about the genesis of the Broadway musical form in 1866 with The Black Crook, was — oddly enough — something of a follow-up to Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Don Walker, who did the snazzy orchestrations for the Lorelei Lee show, was asked by Sigmund Romberg's widow to put together a musical using Siggy's musical leftovers. (Walker got his start as the arranger of Romberg's radio show; when the composer/conductor went on tour in 1935, he didn't want to lose Walker or pay him — so he got his publisher to put Don on contract orchestrating Broadway shows, alongside Russell Bennett and Hans Spialek.)

Walker, with a bunch of musical manuscripts in hand, called on Blondes lyricist Leo Robin, co-librettist Joseph Fields, and choreographer Agnes de Mille. Pink Tights is an operetta, yes, and I'm not much of an operetta fan; but the score is surprisingly likable and altogether charming. The word "charm" certainly describes star Zizi Jeanmaire, the girl who held her own against Danny Kaye in the 1952 Frank Loesser/Moss Hart film "Hans Christian Andersen." Happily chewing the scenery is Brenda Lewis, as a mid-19th-century Liz McCann. She gets to lead a quartet in one of the best no-business-like-show-business anthems: "You've got to be a little crazy," it goes, "to want to produce a play." Here is Leo Robin, of "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend" and "Little Girl from Little Rock": "There's a charm in the smell of greasepaint/that is stronger than all magic spells/you're not Edwin Booth and you won't face the truth/that it isn't the greasepaint that smells."

|

|

|

(Steven Suskin is author of the recently released updated and expanded Fourth Edition of "Show Tunes" as well as "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," "Second Act Trouble" and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He also pens Playbill.com's Book Shelf and DVD Shelf columns. He can be reached at [email protected].)

Visit PlaybillStore.com to view theatre-related recordings for sale.