*

Things to Ruin [Ghostlight 8-4445]

Composer-lyricist Joe Iconis' Things to Ruin starts out with a song that goes "I was born this morning, gonna die tonight" and continues with a song that goes "Mamma, cut me deeper, cuz if I see I'm bleeding then I'll know that I'm alive." I don't think the singer is actually talking to his mother, standing above him with a Sweeney-razor. It's not that kind of a show. I think.

Now, these two tracks might not sound like the type of musical you want to listen to; I certainly had misgivings about continuing with the two-disc cast album of Things to Ruin. But maybe, just maybe — I thought — Mr. Iconis has something to say, something up his seemingly blood-soaked sleeve. So I persevered, and was almost immediately rewarded. The third track, "Nerd Love," is written in the same language as the first two but turns out to be an interesting and attractive — if unconventional — duet.

The fourth, "The War Song," is yet again unconventional but arresting; the singer is a post-Columbine teen with no future, thus choosing to go to war. "Don't care when or where, nah I'm not choosy, don't have any patriotic passion or national rage; just wanna take a cool picture of me with an uzi, and post it on my Facebook profile page." It's a new world, as Tevye used to say; this character, and all the characters in Things to Ruin, live in this new world, and Mr. Iconis speaks the lingo. And that's the point, it seems; this score might not be in the 20th century American musical theatre tradition, but we ain't livin' in the 20th century anymore.

That, in itself, is not the reason to pay attention to Things to Ruin. Once Iconis has sufficiently shocked and awed us, he turns out some theatre songs that are good by any standard. "Asleep On My Arm," for example, in which Iconis draws a character — an immature college-type — and shows him starting to grow within a three-minute slice of time, simply because this girl likes to sleep on his arm and (he muses wonderingly) maybe deserves to sleep on his arm. For now. It turns out that Iconis has a talent for creating character in song; these characters are very much today, and they and their author seem to be a generation or more younger than the Adam Guettel-Jason Robert Brown-David Yazbek group. Iconis has talent, a refreshing voice, and an ability to make us listen. "The Guide to Success" is blatantly cynical in a shark-eat-shark way ("eventually every relationship ends, so throw out your baby and murder your friends"). "Headshot" is A Chorus Line updated; "Things will be a better with a better headshot," sings the out-of-work actress. The second disc, which I suppose represents Act 2, offers a searing song about a high-school kid waiting to be picked for a "Dodge Ball" game, petrified that he will be chosen last; and another about a pre-teen whose best (and only) friend moves away to Albuquerque. With these two songs plus the aforementioned "Asleep On My Arm," I totally forget about dying tonight and "mamma cut me deeper"; anyone who can write these three songs earns my eager attention. The cast includes seven young singers, none of whom I believe I have previously made the acquaintance of. But I shall look out for some of them. (One, who does so well with that "Asleep on My Arm," is Nick Blaemire, composer/lyricist of the infamous Glory Days .) Iconis himself pounds the score out at the keyboard, and distinctively delivers the shark-eat-shark song.

Things to Ruin falls somewhere between a revue and a song cycle, I suppose; it is different, yeah, but that is one of its several charms. It was first performed at the now-departed Zipper Theater, opening for a month on Halloween 2008; it was remounted for two weeks in the spring of 2009 at Second Stage. I didn't catch Things to Ruin in the theatre, but I'm glad to have caught up with it on CD.

|

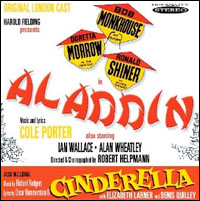

Those written-for-television musicals of the 1950s and 1960s, written by some of Broadway's top songwriters, were written for television and specifically not intended for the stage. These guys — Rodgers & Hammerstein and Porter, for example — knew what they were doing; while lesser talents might write a television musical with hopes of a transfer, items like Rodgers & Hammerstein's 1957 Cinderella and Porter's 1958 Aladdin were not devised for the stage. If they were, they would have been written in a different manner. This has not stopped producers, with dollar signs in their eyes and a lack of theatrical craftsmanship, from plunging ahead. The pitfalls can be experienced by the two stage adaptations included on the disc in question. London showman Harold Fielding saw Cinderella — by the world's most successful show-writers — as perfect fare for a big 1958 Christmas show at the London Coliseum starring Tommy Steele. Steele played Buttons, a character grafted onto the proceedings; but transforming a well-crafted 75 minutes into a full-length affair meant adding and padding.

The following Christmas, Fielding struck again with a bloated Aladdin. Cinderella, at least, was built on a charming score and workable trappings; Aladdin, written when Porter was ailing and ready to throw down his rhyming pencil, was pretty lousy on television to begin with. Fielding's team — director/choreographer Robert Helpmann, librettist Peter Coke and "additional material" provider Denis Goodwin — did what sounds like a poor job. It is all pretty sorry; and some of these lyrics serve to make Porter look bad, like the ones about Chou En-Lai, Ike-Nikita-&-Mac (presumably Prime Minister Harold Macmillan), Orange Pekoe tea, and an emperor who says "Me no telly." None of these are included in Robert Kimball's definitive "The Complete Lyrics of Cole Porter," so let us assume that this is what Mr. Goodwin contributed.

Interpolated Porter songs include "There Must Be Someone for Me," from Mexican Hayride; an extremely poor version of "Ridin' High," from Red, Hot and Blue; and two from Cole's 1950 failure Out of This World, "Cherry Pies Ought to Be You" and "I Am Loved." (In the last case we are rewarded by hearing it sung by Doretta Morrow, a major asset of the original Broadway productions of The King and I and Kismet.) The production also starred Bob Monkhouse as Aladdin and Ronald Shiner as the Widow Twanky. Wherever did Aladdin run into Twanky, I wonder?

The tracks from Cinderella are not from Fielding's Coliseum production; this is, rather, a studio cast album of the initial stage version of the television musical. If the notion of a studio cast album of Fielding's stage version of Cinderella, as recorded by an obscure, low-budget label (Saga Records, anyone?), sounds questionable to you, I was ready to bypass these tracks altogether.

But what do you know? It sounds pretty good. Cinderella is sung by Elizabeth Larner, who a few years later would create the Julie Andrews role in the London premiere of Camelot. The surprise, here, is Denis Quilley as the Prince. I had a vague recollection of enjoying Quilley when I saw him, as a child, playing opposite Elizabeth Seal in Irma la Douce (in which he replaced Keith Michell); and he is hands down the best Judge Turpin I've yet seen. But here, singing the Prince, he makes these songs sound better than I have ever heard them. "These songs," in this case, include two interpolations from Me and Juliet, "No Other Love" and "Marriage Type Love." If the notion of Cinderella's Prince dreaming of the homey comforts of "Marriage Type Love" sounds strange to you, you're right. But Quilley sure sings it. This Cinderella features a humorous rendition of "The Stepsisters' Lament," sung not by two character comediennes but by one actor named Dudley Rolph. (I suppose that Fielding, in keeping with the Christmas panto tradition, must have placed men in the roles.) Orchestrations for these low-budget affairs are usually very much suspect, so let me add that while these — from orchestrator Gilbert Vinter, leading the London Variety Theatre Orchestra — are not up to Russell Bennett's lofty standards, they are very much all right.

|

||

| Hugh Martin |

||

| photo by Bill Wechter Photography |

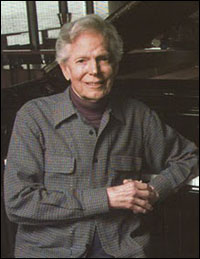

Years ago I received an effusive, handwritten letter thanking me for a column I wrote praising one of Martin's scores. I responded with a letter, he wrote back, and we continued writing and talking until last month. This was not uncommon, mind you; I've run into perhaps a dozen lovers of fine theatre music who had the very same relationship. Hugh knew just how good his finest songs were, but he always seemed surprised to learn that members of the younger generation felt the same. (If you were born in 1914, just about everyone you came across after 1975 was a member of the younger generation.)

Hugh would be the first to say that he doesn't in any way belong on the shelf with the likes of Rodgers, Gershwin, Kern, Porter, Arlen and Sondheim. That said, the best of Martin's songs do qualify; his most beautiful songs are not heavenly but unearthly, with luscious harmonies that nobody else could ever stumble upon. (There is no reason to trot out Mr. Sondheim's list of "Songs I Wish I'd Written, At Least in Part," but it should be noted that said list includes three songs each from Berlin, Bock, and Porter; two from Kern and Rodgers; one from Gershwin; and four by Hugh Martin. There are five by the great Harold Arlen, but Hugh — and I, for that matter — certainly agree with Sondheim on that.)

|

And that's the magic of Hugh. His scores have their ups and downs, yes; I don't think he aspired to write the greatest music in the world, because he knew he couldn't compete with his idols (Rodgers, Arlen, et al). What he did want to do was provide his listeners with fun; fun that would leave them grinning with joy as if they just jumped off a trolley with their heartstrings plucked, the universe reeling, and that clang-clang-clanging still in their ears. All of this can be sampled on your piano bench with the 2008 folio "The Songs of Hugh Martin" and is discussed in the 2010 autobiography "Hugh Martin: The Boy Next Door." What's more, there's a CD of Hugh's hidden treasures — tentatively entitled "Hugh Martin's Hidden Treasures" — expected this summer. (For a little more context, here's my 2006 column about the PS Classics disc "Hugh Sings Martin.") One can't mourn a 96-year-old who led a full and productive life, especially when he had the satisfaction of hearing his music flood the airwaves every December. (He was amused when I emailed him one day to tell him that my corner store, Bloomingdale's, had his 1944 Christmas song — here in the 21st century — booming out on the sidewalk from their Lexington Avenue windows.) So no mourning for Hugh Martin. We'll miss him, but we'll forever have those songs.

(Steven Suskin is author of the recently released updated and expanded Fourth Edition of "Show Tunes" as well as "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," "Second Act Trouble" and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He also pens Playbill.com's Book Shelf and DVD Shelf columns. He can be reached at [email protected].)

*

Visit PlaybillStore.com to view theatre-related recordings for sale.