*

Actors' Equity Association is that most improbable of institutions: an artists' union. It represents and looks out for the welfare of more than 48,000 actors and stage managers in the United States. In 100 years, it has not imploded, been exploded, or been declared illegal. It should be in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

As a journalist, I have covered the American stage for 30 years. During that time, I have tended to take Equity for granted as one of the immutable realities of the theatre. Yet, as I researched this book, it quickly dawned on me that Equity's very existence was basically unimaginable. We tend to associate unions with blue-collar jobs — work that is often hard and unglamorous to begin with and would be so much worse if a union didn't look out for its practitioners. A labor organization representing an inevitably elective profession like acting? Absurd, really. Surreal. Artists have never managed it. Nor novelists, nor poets. That a labor union governed by performers, and speaking for performers, has survived for a century is nothing less than a miracle.

Certainly the people who controlled the theatre back in 1913 didn't think Equity would last a year. Actors were too self-interested ever to act in concert; too proud ever to call what they did a craft; too refined and impractical ever to worry themselves with the base matters of business; and too insecure ever to turn down work, no matter how financially punishing and personally humiliating the conditions. So went the conventional wisdom. And for much of the 19th century, the evidence did not seem to contradict it. Every attempt to organize actors had failed.

But by the 1910s, working conditions had become unendurable. Actors were not paid for rehearsal. They were made to buy their own costumes. They were abandoned when shows failed on the road. Contracts were regularly broken by unscrupulous producers. There was no security. Action had to be taken. And in 1919, it was. The fledgling union found its feet and its teeth six years after it was formed. To purchase "Performance of the Century," visit the Playbill Store.

|

||

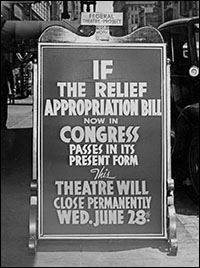

| Sign from 1939 appealing for public support. |

||

| Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lennox, and Tilden Foundations |

Beyond that, Equity has forever sought to advance, promote, and foster the art of live theatre a country that often seems defiantly predisposed to reject the role of art in daily life.

Of course, Equity accomplishes many more mundane, but no less important, things on a daily basis — such as ensuring that professional workplace standards are upheld and theatre professionals are fairly compensated, adequately insured, provided a secure retirement, and protected from discrimination. It manages this through the National Council, Equity's policy-making and governing body, the members of which live within Equity's three geographic regions (Western, Central, and Eastern). The Council defines the authority and duties of three Regional Boards and many committees, and oversees their actions. As such, the union essentially remains a democratic enterprise, the members' collective voice leading the future direction of Equity.

|

||

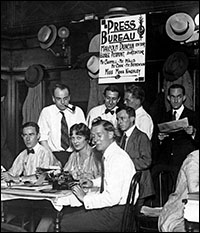

| Press bureau for the 1919 AEA strike. |

||

| Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lennox, and Tilden Foundations |

Stage mangers would seem to be the odd ones out in that list. But they have always been part of Equity. The reason for this is simple. In the old days, there was a little bit of actor in every stage manager, and a little bit of stage manager in every actor. Before stage work became a complex business, and theatre professionals were compelled to specialize, the positions were more fluid. An actor might take a stage managing gig between roles, and a stage manager might be called on to step into a performer's shoes. If theatre is a collaborative art, as they say, many of its collaborators can claim a connection to Equity. Directors and choreographers, too, can consider the union their original home. Prior to the formation of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society in 1959, directors' contracts with producers were negotiated by Equity. Given the long history of the actor-manager, who wore many hats, including director, this arrangement hardly seems strange.

To purchase "Performance of the Century," visit the Playbill Store.

|

||

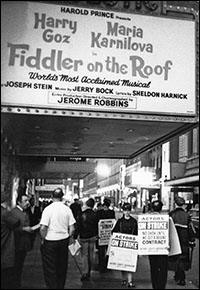

| Picketers in front of the Majestic Theatre during the 1968 AEA strike. |

||

| Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lennox, and Tilden Foundations |

It's an unbalanced world we live in today. The unions that represent the teachers that school our children and the workers that help run the government are being attacked and weakened by politicians bent on demonizing labor in general. Yet the theatre, the most impractical and dreamy-eyed of all areas of endeavor, remains strong. Walk into a theatre on Broadway and everyone you see — the actors, ushers, stagehands, musicians, directors, choreographers, playwrights and, yes, actors — belongs to a union or guild. Few of us look up at the man or woman in the spotlight, selling that number or delivering that soliloquy, and think, "union member." Why do they need a union? They're doing what they love. They're enjoying themselves.

Well, maybe they need a union so they can continue doing what they love, what we love.

"We're celebrating the history while we're diving into our future," said Mary McColl, executive director of Equity of the centennial. "It's exciting trying to figure out where the union stands in 2012. How you can take this thing that's been around forever, this tradition-laden thing, and take it into the modern age? How do we go from this hundred-year-old entity to a progressive forward thinking member of the industry to ensure that there are jobs for actors on the live stage 10, 20 and 30 years from now?"

Without Equity, there would still be actors and stage managers. There's no dissuading those who seek the footlights or those who position them. But there would probably be fewer of them, fewer good ones, and certainly fewer happy ones. Which would likely result in many fewer exultant theatergoers, and an impoverished culture. Actors, like their brothers and sisters in labor, are teachers of a sort. They teach us about life through characterization, lending flesh and blood to the playwright's words and ideas. There's an old show business saw that goes, "Those who can't act, teach." Well, those who can, teach too. That someone supports them isn't a bad thing. For a century, Equity has been that someone. The union protects artists while they practice their craft, their art, their profession. *

From "Performance of the Century: 100 Years of Actors' Equity Association and the Rise of Professional American Theater" by Robert Simonson. © 2012 by Actors' Equity Association, published by Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, an imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation. Reprinted with permission.

To purchase "Performance of the Century," visit the Playbill Store.