*

The anticipatory buzz that precedes a major Broadway opening wore a silencer on March 15 — the Ides of March — and a distinctly reverential tone hovered over first-nighters who filed into the Barrymore Theatre to praise Caesar, not to bury him.

Caesar, in this case, is the King Lear of American drama, Willy Loman, created by Arthur Miller in his masterpiece, Death of a Salesman, in 1949 — a road-worn traveling salesman at the end of the line, having run on empty longer than the law allows and now inequitably dry of the optimistic helium that has kept him going. He slogs heavily home, lugging two leaden sample cases as the curtain rises.

It rises on Jo Mielziner's original skeleton set of Loman's almost-paid-for Brooklyn abode, and the forlorn woodwind wail which Alex North composed for the first production underscores the fact that, emotionally, this is the dark side of the moon.

We are, like Willy, home — savoring a sense of what serious theatre must have been like 63 years ago, here painted back into place with delicate, masterful strokes by director Mike Nichols, who witnessed Elia Kazan's famed production and clearly can approximate those old emotions that connected stage and audience. In a day when classic theatre is being dismantled and "re-imagined," it's a lovin' feelin'. Willy Loman has never been away from us for long, it seems, making his Main Stem rounds with commendable regularity in the shaky forms of Lee J. Cobb (1949), George C. Scott (1975), Dustin Hoffman (1984) and, most recently, a Tony-winning Brian Dennehy (1999). Now, another Hoffman is heard from.

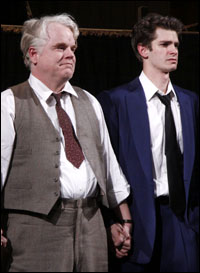

There was no star-entrance applause (thank God!) for Philip Seymour Hoffman — the audience, as noted, arrived "with it," ready for The Real Deal — as Willy weaves his way home again, "a little boat looking for a harbor." His blond locks silver-up under Brian MacDevitt's murky lighting, and he moves with a steady-as-she-goes, ungainly gait of a Charles Durning or a Victor Moore.

[flipbook]

In his two previous, Tony-nominated outings on Broadway, Hoffman was a troubled son/brother — juggling two of them at once in back-and-forth rep in True West and playing Dennehy's alcoholic first-born in Long Day's Journey Into Night — so there was some initial concern that, at 44, he might be too young to play such an old ruin, but a few right, arthritic moves soon stilled that doubt.

Cobb was 38 when he originated the role of Willy Loman, but then he was a born character actor. A decade earlier, he played (with more zinc oxide than conviction) father to a seven-year-younger William Holden in the film of Clifford Odets' "Golden Boy."

Miller conceived of Willy as a small man but eventually realized the actor he wanted for the part — Roman Bohnen — lacked the size of the character even though he fit the body. Like Cobb, Bohnen was a Group Theatre regular (Waiting for Lefty, Awake and Sing!, Golden Boy) — and, on screen, a subtle, often overlooked actor. His best bit was Candy, the ranch-hand whose dog had to be put down in "Of Mice and Men." He also fathered Jennifer Jones in "The Song of Bernadette" and Dana Andrews in "The Best Years of Our Lives." Loman would have made him a star. Losing the part and making the HUAAC blacklist stressed him into a fatal heart attack exactly two weeks after Death of a Salesman opened.

Buy this Limited Collector's Edition |

And, under Nichols' meticulous and compassionate direction, the sounds of the father are inherited by the sons. Hoffman's individual and unmistakable style of arguing — full-out, frontal rage — is echoed by his boys, by Andrew Garfield's Biff and Finn Wittrock's Happy. No mystery where they picked that up.

With all that twisting and shouting on the homefront, the metallic tinkle of Linda Emond's Linda Loman somehow manages to be heard. The most visibly painful aspect of her performance is her unwavering protection of her lost-cause husband.

There is some nice luxury casting in the supporting roles: Tony winner John Glover comes and goes as Ben, the brother who got away and made a mythic killing in the wilderness of Willy's mind, and Obie winner Bill Camp is the friend next door Willy never really liked who musters the play's most poetic epitaph. In a solid Broadway debut, Fran Kranz is the latter's son, a hopeless nerd who made something of himself and put Willy's roiling litter to shame. Remy Auberjonois is the uncaring son of Willy's beloved boss, only too happy to put him out to pasture. Throughout the supporting ranks, there are little, life-giving touches from Nichols: The chippy that Willy chases in Boston (Molly Price) is convincingly on the chunky side; the bartender Willy suicidally overtips (Glenn Fleshler) kindly returns the money to his pocket, et al . . .

The cast of 17 — an anomaly in these hard economic times which the play addresses so directly — stood tall for the curtain call and stayed in place for a second one, egged on by the bravos and ovations of their starry, show-savvy audience. Doing their darnedest to skip the press line and paparazzi in front of the Barrymore: Mrs. Don Gummer (La Streep, who owes some of 17 Oscar nominations and one of her Emmys to Nichols), Stephen Sondheim and Emma Stone of "The Help," Garfield's main-squeeze and the distressed damsel in his forthcoming "Amazing Spider-Man" movie which will be web-slinging into theatres soon.

| |

|

|

| Philip Seymour Hoffman and Andrew Garfield | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Jeffrey Wright (who owes his Tony to Wolfe and his Emmy to Nichols for the same performance in Angels in America) was also in attendance, as were Chris Messina, entertainment attorneys Jason Baruch and Mark Sendroff, New York City Ballet's Jacques d'Amboise, Entertainment Weekly editor Jess Cagle, Tony nominee Bobby Cannavale (now of "Nurse Jackie" and "Broadwalk Empire"), Charlie Cox of the latter, Bill Hader of "Saturday Night Live," Marlo Thomas (who starred for Nichols on Broadway in Social Security), Tony nominee Stephen McKinley Henderson, set designer Tony Walton (bracing himself for tears at seeing Jo Mielziner's set again), playwright Rob Ackerman (whose Call Me Waldo just ended a sold-out run Off-Broadway and who has already starting writing his next, Mookie, the Cat From Harlem), playwright Paul Rudnick (who's branching out into young adult novels and adapting "Summit" for the screen). Rosie Perez (who got to keep the sensational white coat she wore in Close Up Space), four-time Tony winner Zoe Caldwell (whose late husband, Robert Whitehead, co-produced Dustin Hoffman's Death of the Salesman), producer Jon B. Platt (who received CTI's Robert Whitehead Award earlier in the week and is on board for this revival) and Anna-Deavere Smith.

Broadway-bound themselves are Boyd Gaines, who's playing Stewart Alsop, brother of The Columnist, Joseph (John Lithgow), right next door to the Barrymore at the Biltmore; and Carol Kane, who'll play Charles Kimbrough's wife in the Broadway revival of Mary Chase's Pulitzer Prize-winning Harvey, arriving June 14 at Studio 54. Kane was in Nichols' "Carnal Knowledge" — and "we've gone to a lot of plays and done a lot of dinners since."

Couples included "The Good Wife" and her good husband (Julianna Margulies and Keith Lieberthal), Diane von Furstenberg with Barry Diller, columnist Liz Smith with fellow Texan, publisher Joe Armstrong, a tres pregnant Maggie Gyllenhaal and Peter Sarsgaard, the Tony-nominated duo of The Goodbye Girl (Bernadette Peters and Martin Short). Arriving separately, thus keeping his face martini-dry: that splashing "Smash" pair — Oscar winner Anjelica Huston and Pulitzer Prize winner Michael Cristofer.

Very much playing the good wife: Diane Sawyer, becalming a nervously smiling Nichols in an alcove leading to the box seats just before the show began.