*

This feature could have been titled "David Mamet's Five Most Memorable Characters," and the same names would probably have turned up, so dominated by the male of the species is the Mamet canon. From the time the playwright burst upon the American stage with American Buffalo — the first Mamet play most theatregoers saw, and still one of his most produced — the Chicago-born author's fictional stomping ground has been a man's, man's, man's, man's world. American Buffalo sized up the desperate and doomed gambit of a trio of small-time crooks, all possessing a Y chromosome. There wasn't a skirt in sight. A Life in the Theatre, in 1977, looked at the trials and tribulation of two actors — two male actors. Edmond (1982) tracked a middle-aged married man as he bolts his staid life and embarks on a hellish descent into vice and criminality. Speed-the-Plow counts a woman — a secretary with no last name — among its figures, but the play is really about the challenged friendship between two Hollywood alpha males.

There are exceptions, of course. The Cryptogram featured a mother as its central character. The arch comedy Boston Marriage was about the possibly romantic relationship between two females at the turn of the 20th century. And Mamet's latest work for the stage, The Anarchist, due on Broadway in November, also has an all-female cast; Debra Winger plays a warden, and Patti LuPone an inmate.

Still, the prototypical Mamet play is more like Glengarry Glen Ross, which is also being produced on Broadway at the moment, in a production starring Al Pacino and Bobby Canavale. Women may as well not exist in the testosterone-heavy real estate office in which the 1984 drama largely takes place. There are seven characters, all hombres. In the play's cutthroat business environment, they can be evenly divided into predators and prey (with some predators becoming prey as the action proceeds). They brag, they boast, they bluster, and they curse. Oh, do they curse! Profanities are the nouns, verbs, adjectives and exclamations of their personal lexicon, and they can find a hundred meanings and variations in an F-bomb. Yet, for all their braggadocio, most of Mamet's men are panicked inside, aware the world and circumstances are closing in on them, and that their hard-won, hard-sold, hyper-male shell is the only thing that keeps them from cracking, their underbelly exposed to the heartless world.

| |

|

|

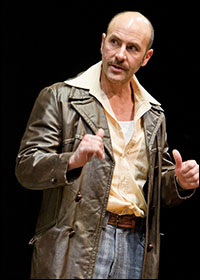

| Jordan Lage in Mamet's American Buffalo at Baltimore CenterStage. | ||

| photo by Richard Anderson |

| |

|

|

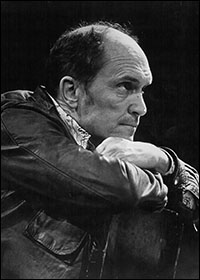

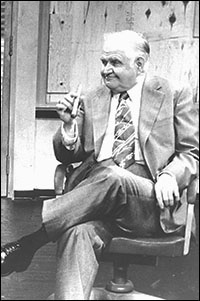

| Robert Duvall in the 1977 Broadway production of American Buffalo. | ||

| Photo by Roger Greenwalt |

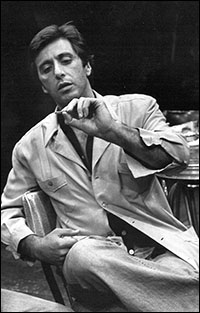

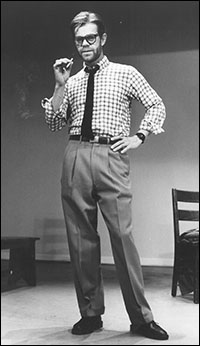

Mamet males usually spend the play trying to make something happen, something that's going to make their fortune and prove their worth on the street. Often, it's something illegal. Such is the case with long-suffering small-timer Walter Cole, known by his and colleagues as "Teach." In American Buffalo, he and his pal Don, who owns a junk store, hatch a scheme to rip off a local coin collector. The half-baked plan quickly goes awry, of course, and the play culminates with a volcanic exhibition of Teach's pent-up frustrations.

Though the roles of Don and the dim-witted youth Bobby have their attractions, the play belongs to Teach, and actors have long been drawn to the character's mix of pathos and emotional histrionics. Robert Duvall, Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman and William H. Macy have all portrayed him. And, according to Macy, there's a kinship between such actors. "Dave is the guy who found the music in American speech, unlike any playwright before him," said Macy, who filled the role in an Atlantic production. "When you find two guys who have done American Buffalo, they start doing the lines together. Just like, 'Did you do Sound of Music?' and they'll start singing the songs."

"That's one of those roles that everybody wants to play," said Neil Pepe, artistic director of the Atlantic, who directed Macy in the drama. "It's a cathartic role. It begins with an incredibly well-written rant. It's based on a story of Mamet and Macy living in Chicago. They had no money. Mamet walks in and opens the refrigerator and takes some food out and Macy says, 'Help yourself.' Mamet was so pissed off at Macy for hassling him for taking some food that he wrote that monologue. It not only has that, but it has this thing about small-time businessmen and guys who think they're more than they are, and then betrayal. It's so much about fathers and sons and loyalty and that brotherly feeling between those guys."

| |

|

|

| Al Pacino as Teach in the 1983 Broadway revival. | ||

| photo by Stephanie Sala |

Lage continued, "Teach is a very wounded guy, mostly by his own hand. But having played the character twice — during my undergrad days at NYU and 28 years later last fall at Baltimore's Center Stage — it would follow that I have great empathy for him, faults and all, as does his friend in the play, Don. Explosive, conniving, sociopathic, vulnerable, out of his league around those smarter than him and extremely sensitive about it, Teach struggles to carve out what he perceives to be his entitled piece of the American Dream. In the course of the play, he's foiled once again, not fully realizing the failure is mostly of his own making."

Comic, tragic, smart, sociopathic, vaudevillian, vulnerable, empathetic. Who wouldn't want to play that guy?

| |

|

|

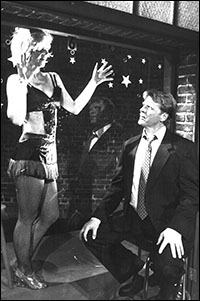

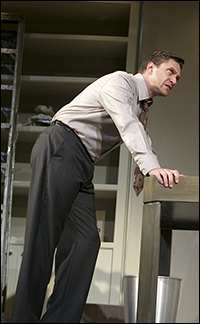

| David Rasche (with Mary Anne Urbano) in the Atlantic Theater Company's Edmond. | ||

| Photo by Elizabeth Messina |

The title role in Edmond is probably the least-known of the roles on this list. In many ways, Edmond is an anomaly. Many of Mamet's plays take a dim view of existence, but this 1982 work is relentlessly dark, and unusually expressionistic, taking the anti-hero through the seedier byways of urban life, all the way to prison. Unlike most of the other works by the writer, which are typically divided into two or three big scenes, the action is told in 23 short episodes. Moreover, here we have one male protagonist — not two, not three — on which all attention is focused. The play is rarely staged, but when it is — a production at the Atlantic in 1996; a 2003 London staging starring Kenneth Branagh — it is usually praised. Among Mamet veterans, it is reserved a special admiration.

"Why is it one of the great roles?" asked Neil Pepe. "Because it's a man who chooses to remove himself from his life and go on this odyssey and rediscover himself. In terms of an arc, and a guy who's on a quest to own who he is, it's a remarkable journey. In some ways, it's Mamet's darkest play. It's aged well. It's about this guy opening himself up, and getting in a lot of trouble, and finding his way back."

"Edmond is unlike any other character in Mamet's work, or for that matter American drama," offered Mosher. "His journey through rage and mysticism to redemption is the stuff of 19th century Russian novels. The final scene of the play, when Edmond is in the cell with another prisoner talking about the supreme animals from outer space and quoting Hamlet, is the most moving thing he's ever written."

Lage called the story "A dark spiral. Thank god it's just a play. It's an amazing ride to the dark side for Edmond. But 'every fear hides a wish,' and in the end, after he's vented his homophobic and racist panic, he seems to have found true happiness, as disturbing as it is. Just an incredible journey that the actor takes during the course of this play… As an NYU intern in 1982, I house-managed the original New York production at the Provincetown Playhouse and got to see Colin Stinton in the title role dozens of times. For me, Colin perfectly embodied the staid, buttoned-up model of white collar middle-class repression. Restless, mid-life crisis pulling at him, he walks out on his wife and so begins his descent into New York's underbelly… The actor playing Edmond must curry empathy while being emasculated at the beginning of the play, convincingly tap into adrenaline-fueled blind rage in the midsection of the play, and evince a tenderness and beatitude by play's end. A great challenge, immensely rewarding for an actor who can pull it off."

| |

|

|

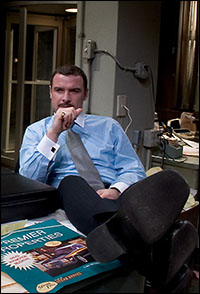

| Liev Schreiber as Ricky Roma in the 2005 Broadway revival. | ||

| Photo by Scott Landis |

There are seven good roles for men in Glengarry Glen Ross, and two great roles. The other great part, Shelley "The Machine" Levine, an old drummer about to go under for the last time, could easily have been on this list. (Indeed, a few interviewed for this article suggested it should be.) But this vibrating potboiler of deceit and desperation really belongs to Ricky Roma — an opinion Roma would surely agree with. The office hotshot, the firm's best seller, Roma is a showhorse who never passes up an opportunity to boast of his numbers or his prowess with a pitch. He's got the best patter, the sharpest suit, the nicest car. He's the sleekest shark in the tank. It's no coincidence that when the show is done on Broadway, it's the actor playing Roma who takes home the Tony — Joe Mantenga in 1985; Liev Schreiber in 2005.

"It's pure unadulterated joy playing Ricky," said Schreiber. "The guy's inner tempo is incredible. To me he's the intellectual equivalent of a trapeze artist. He's just so quick on his feet. And so unabashedly narcissistic. That's really from the play. Because we're not supposed to be that way in real life. But Ricky doesn't give a shit."

"Roma is, of course, classic Mamet," said Lage, who understudied Schreiber in the 2005 Broadway revival, and went on several times. "Smooth-talking, profane, driven, determined, magnetic, the merciless alpha male shark of the real estate office, he does not suffer fools gladly. He allies himself with those he thinks will benefit him and humiliates those he has no use for. And the audience loves him for it. Seriously, Roma could be a cult figure to some."

"Performing the role," Lage continued, "I found that the audience just eats Roma's scenes up. The key in performance is picking up the pace and speaking up — literally, talking loud and keeping the putdowns coming fast and furious. He ruthlessly walks all over these guys. I remember seeing Joe Mantegna several times in the role. He had the audience eating out of his hand. Joe had achieved a kind of rock-star status with those audiences in that original production." Lage added, "I believe that if the actor playing Roma isn't generating that kind of giddy mirth in the audience in Act Two, he is doing something seriously wrong." During rehearsal for Glengarry, Mosher said he asked Mamet if he thought Ricky was the kind of guy who would think the glass is half-full or half-empty. "He said he's the kind of guy who'd give you the history of water, starting with the cavemen."

| |

|

|

| Raúl Esparza as Charlie Fox in the 2008 Broadway revival of Speed-the-Plow. | ||

| Photo by Brigitte Lacombe |

Charlie Fox would recognize Ricky Roma as one of his own breed — dresses well, talks fast, accepts nothing less than success and always on the make. But Charlie might think Ricky was in a chump profession. Real estate? How much green, in the end, can you make from that? And where's the glamour? Now, movies — there's a field!

Speed-the-Plow is Mamet's Hollywood play. Same snakes, different city. In the three-hander, independent producer Charlie Fox pitches his pal, newly appointed studio head Bobby Gould, with a package deal surrounding a reigning film star named Doug Brown. The project is green-lighted — until Bobby's idealistic secretary weasels her way into Gould's affections and convinces him to make a serious movie about the effects of radiation. The disbelieving Fox explodes, becoming perhaps the only man in Hollywood history, actual or fictional, to seal a deal by clocking a studio honcho in the face.

The play had a memorable debut, with Joe Mantenga as Gould, Ron Silver as Charlie and none other than Madonna as the secretary. It was revived on Broadway in 2008. That staging became infamous for cast member Jeremy Piven's sudden departure, leading to array of players replacing him as Gould, including Lage, Macy and Norbert Leo Butz.

Similar to Glengarry's balance between Levine and Roma, Speed's protagonist would seem to be Gould, but Fox is really the headline-grabbing part. He's the firecracker; the scrappy, funny one; the man whose suit is cut as sharp as his stiletto. Silver won a Tony for his performance, and Esparza, who played it in 2008, was nominated.

| |

|

|

| Ron Silver and Madonna in the original Broadway staging. | ||

| photo by Brigitte Lacombe |

"His bluntness and savagery are, like Roma's, pure audience crowd-pleasers," stated Lage, "and the actor playing him can have a ball. Mamet, of course, is a genius wordsmith, and he gave Fox some of the choicest lines in his entire canon." He added, "Fox and Gould's rat-a-tat dialogue together in Act One is about as close to a duet without singing as you can come."

"No question," said Pepe, who directed the 2008 Broadway production. "That's the part. He's not the anchor; Bobby Gould has all the power. But Charlie's life is on the line. He's got the great first speech. And then he goes ballistic when he feels like he's been betrayed. It's that same three-character structure [as in American Buffalo], but Mamet reinvented it for Hollywood."

Mosher, who directed the premiere of the play, also saw a connection to American Buffalo. "Clean Teach up, put him in a Versace suit, send him to Hollywood to make movies, and he's Charlie Fox in Speed-the-Plow."

| |

|

|

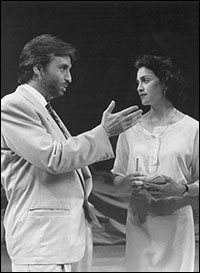

| William H. Macy as John in the original Off-Broadway production of Oleanna. | ||

| Photo by Brigitte Lacombe |

You wouldn't describe the dialogue between the two adversarial characters in Oleanna as singing. More like two gears angrily grinding against each other. This 1992 two-character play instantly became controversial hot ticket upon opening Off-Broadway, with Macy as John, a professor, and Rebecca Pigeon (Mamet's wife) as Carol, his student. Audiences spilled onto the streets, arguing the sides of each characters, and debating who was in the wrong.

In the play, Carol comes to John during office hours seeking help with the material assigned in his class. Certain ambiguous gestures and comments are misinterpreted and, by the second act, Carol has filed a formal complaint against John, accusing him of sexual harassment. Their relationship devolves from there, becoming more confused and combative, leading to an ending of surprising violence. Audience viewed the production as a blistering look at political correctness, but largely disagreed as to what Mamet's message was.

While Carol was roundly regarded by critics as one of Mamet's most fully realized female creations, John is the prize part here. Depending on your point of view, he's either villain or victim, but probably a mix of both, all the while remaining pathetically human, and a bit grandiose. A feast for an actor.

Macy said that one thing John shared with other Mamet characters is, "that fellow can talk… Actors love the dialogue because it literally feels good to say it. It's got rhythm and meter and poetry. the music in it literally feels good to say. And [Mamet's characters are] oddball characters. Sometimes marginalized characters, but the lead in the play! They're characters that usually don't have stories told about them." "You ever get accused of something you know you didn't do? And your antagonist is utterly convinced of your guilt, no matter your argument?" asked Lage. "That’s John in Oleanna. He also gets off on his role of college professor as didactic godhead. That's his undoing. Arrogant, hubristic, a bit clueless. Perfect qualities for a tragic hero."

| |

|

|

| Robert Prosky as Shelley Levine in the original Broadway production of Glengarry Glen Ross. | ||

| Photo by Brigitte Lacombe |

Let us know who your favorite Mamet men are by posting a message on the Playbill Facebook page or following us on Twitter @Playbill.

Al Pacino and the Cast of Glengarry Glen Ross Tackle David Mamet's Musical Language