In the history of show business, no one has bitten the hand that feeds it harder that the dramatists moonlighting in Tinseltown. Feeling their talents and dignity have been affronted by a colony of shallow, megalomaniacal egomaniacs, they reach for their trustiest weapon—the pen. The tradition goes back as far as the 1920s, when George S. Kaufman—who would see many of his stage successes made into film—mercilessly sent up the film world in Merton of the Movies. He offered up a second helping of abuse in 1930 with Once in a Lifetime. His satiric sword has since been taken up by the likes of Clifford Odets, David Mamet, David Rabe and many, many more.

Here are Playbill.com's picks for the five best Hollywood hatchet jobs.

|

||

| George S. Kaufman |

"No sooner were there movies then there were plays spoofing the movies," argued film and theatre critic Robert Cashill, who writes for Popdose.com and Theaternewsonline.com. Merton, he was, "left footprints, by establishing a basic template for the genre, with an idealist adrift in fast-talking, morally screw-loose, scam-ridden Hollywood—I think every subsequent play ever written about La La Land follows it to some degree or another, including The Big Knife, with its conscience-stricken star, and Speed-the-Plow, whose secretary has, or seems to have, upstanding motives. Here movie-mad Merton Gill, lowly clerk in a Midwest general store, puts his dream of stardom into action and heads for the bright lights, where his earnest overacting draws unintended laughs in the dramatic parts a correspondence course in acting prepared him for. The joke’s on Merton as the filmmakers and hustlers around him groom the serious-minded rube into a comedy star, as sophisticated East Coasters skewer West Coast values, and not for the last time." "The Kaufmann and Connelly script is a sweet, funny and painful look into an silent film actor’s hopes of becoming the greatest dramatic actor in all of Hollywood," said John Rando, who has directed the play, and calls it "one of the greatest Hollywood plays of all time." Rando added, "Merton Of The Movies is a hard look at the truth that even though comedy is the bread and butter of Hollywood, most of the time drama will take the cake."

|

||

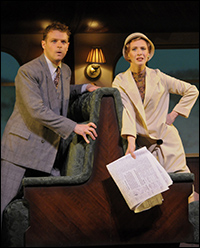

| Lawrence Veil and Julia Coffey in a recent production at ACT in San Francisco. |

||

| Photo by Kevin Berne |

"I've always loved the script," said Neil Pepe, artistic director of Atlantic Theatre Company, which has produced the comedy. "It just captured, at that time period, what it meant to be interested in show business as it pertained to film, and how that played out in Hollywood as opposed to New York. Kaufman and Hart's ability to cut to the humorous truth and the tragic truth of what that business is was just outstanding. Even in contemporary times, writers still talk about what it means to try to ply their trade in movies, how there's a lot of money in Hollywood, and how they get lost in the economic shuffle. In that aspect, like in many others in the play, that play is timeless." "I think Once in a Lifetime is a classic because it manages to be a terrific satire that has a great big heart," said Mark Rucker, who directed the play recently at ACT in San Francisco. "May Daniels is one of the great female characters of the theater in the early 20th century. Acerbic and whip-smart, she uses irony to survive in a man's world where she is surrounded by idiots. But beneath her wit-laden armor beats a heart of gold. After out of town try-outs this play almost died when Kaufman walked away from it. Hart realized that it needed to be a love story as well as a send-up and convinced Kaufman to revised it. Thank goodness, he was right!"

|

||

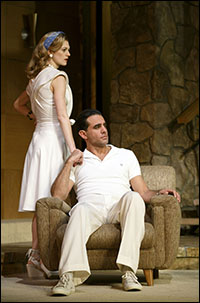

| Marin Ireland and Bobby Cannavale in the current Broadway revival of The Big Knife. |

||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

"Odets wasn't really trying to write a exposé of or satire on the Hollywood star-studio system," commented Time Out New York theatre critic David Cote. "He saw the big money, inflated egos and mysterious aura of movies as a chance to write a play with the feel of a Jacobean tragedy. He wanted blood, bile and spit—and jagged, febrile language… Some of the critics have knocked the play a bit too hard. Sure, it could use a rewrite and lose some heavy-handedness, but I take Odets the way I take O'Neill or Ibsen: Some of it can be overwrought and even laughably pretentious, but it packs a wallop by the end." "Maybe it was the proximity to the show's setting," said theatre journalist Rob Wienert-Kendt of a Burbank production of the play he remembered well. "Maybe it was the casting of non-stars who looked and behaved uncannily like interchangeable vintage contract players (but in a good way), or maybe it was the disarming prospect of an Odets play I hadn't seen before, one that found in studio politics a compelling analogy for larger themes of temptation, success, compromise, and made of it a reasonably taut thriller, as well."

|

||

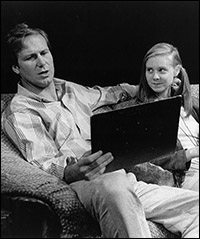

| William Hurt and Cynthia Nixon in Hurlyburly. |

||

| Photo by Martha Swope |

"The characters in this play take a lot of drugs, but what they're really addicted to is the movie business," said playwright Jonathan Tolins, author of the current play Buyer and Cellar, "the money, the excitement, and the promise that they can make something worthwhile in a system that makes it almost impossible. Their behavior may be reprehensible at times, but you always feel the yearning underneath."

|

||

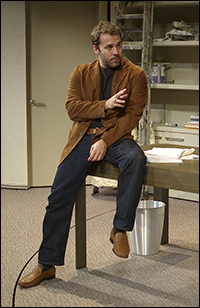

| Jeremy Piven in the 2008 Broadway revival of Speed-the-Plow. |

||

| Photo by Brigitte Lacombe |

"I spent a few years after college temping at the studios and I've always appreciated the way this play turns on the influence of a temporary secretary," said Tolins. "When you work in Hollywood, you spend less time making movies than you do talking about making movies. Everything is determined by the outcome of those conversations—what movies get made, whose careers rise and fall. The pressure is maddening, and since there are no right answers, every county is heard from—even the temp—and that's something Mamet gets so deliciously, ferociously right."

"Speed-the-Plow is the one play" on this list, said Pepe, "that, in terms of the actual business of making movies with the system—the power plays and moral predicaments of getting a film made—that I felt really digs deeply into that questions of moral conscience vs. commercial conscience."

Honorable Mentions: Robert Cashill: "The flim-flammery is alive and well and funny as ever in Jon Robin Baitz’s Mizlansky/Zilinsky, or Schmucks, where bottom-feeding producers pursue one last scam with Oklahoma dentists as ex-wives, hangers-on, and the IRS provide complications." Rob Weinert-Kendt: "I'm intrigued by how Stones in His Pockets and Cripple of Inishmaan tell such contrasting and oddly complementary stories about a film production changing the lives of poor Irish folk." As for me, I've always had a liking for John Patrick Shaley's 1993 comedy Four Dogs and a Bone.