*

David Lindsay-Abaire has returned to Broadway with the style of play that won him a Tony Award nomination and a Pulitzer Prize for Drama for Rabbit Hole — a drama tinged with brusque humor and filled with yearning people who are proud, sad and heartbroken. Good People, now at Manhattan Theatre Club's Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, is set in the area where the writer was raised, in working-class South Boston (known as "Southie"), a neighborhood where the downturn in the economy has stretched an already overextended population. Back in the day, Lindsay-Abaire's ticket out was an academic day pass — a scholarship to a private high school in the affluent Boston suburbs. He was one of the Southie kids most likely to succeed, and he did.

His Good People, directed by Rabbit Hole director Daniel Sullivan, stars Frances McDormand as Margaret Walsh, a paycheck-to-paycheck single mom in Southie who reaches out to an old lover, Mike, played by Tate Donovan, who became a doctor and moved to the other side of the tracks. The tension has been touching audiences, who have been giving the world-premiere production standing ovations since its first week. Lindsay-Abaire talked to us by phone from his home in Brooklyn.

Had you always wanted to write about your old neighborhood?

David Lindsay-Abaire: I'd been wanting to write about it for a long time, but it took me a long time to do it, obviously. There were a couple other attempts to write about something in the neighborhood, but I put them away quickly. They didn't feel right to me, and so I think that I had to mature, both as a person and as a writer, to the place where I felt relatively capable of writing about the old neighborhood. … I don't know if I knew this when I was struggling a few years ago, but now, upon reflection, I guess I wanted to write very responsibly about these people, because I care about them deeply. I wanted to write truthfully and respectfully about them, and maybe it's taken this long for me to do that.

Your early work has absurdist colors. An absurdist play about these people would have not tasted proper…?

DLA: I guess. Maybe it's possible to write that play, but for whatever reason, I didn't feel like I could write the absurdist version of it. I don't want these people to seem ridiculous, because they're so not ridiculous to me. Not that I think of my absurdist characters as being ridiculous, although they do sometimes behave ridiculously. It's more, I think, about perception, and I wouldn't want people to perceive them as being ridiculous.

| |

|

|

| Frances McDormand and Tate Donovan | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

DLA: That I did know, for this play, in particular. I kept hearing, as many of us American playwrights hear, about British playwrights writing about class. "Oh, the Brits always write about class! Where are the American plays about class? Why don't American playwrights write about class?" And maybe they do and those plays just don't get produced. I don't know, but I got tired of hearing about it, and I thought, "Class has always been a huge part of my life." Obviously, I grew up in a working-class neighborhood and I went to a private school when I was 11, and so, I was aware of class all the time, every day, and so it was something that I certainly felt I knew about, so I thought: "I don't know. Maybe I could write about class." The other thing is, I didn't want to write didactically about class. I feel like a lot of British plays about class…are didactic. I sort of feel like, "Oh, there's the playwright up on his soap box, giving me a lecture." And so, I didn't want to write that kind of play, either, obviously. At some point in the process, I thought, "Whatever your ideas of class might be, put that aside. Just write about these people, and the class ideas will come up." And so, I did that… So yes, I was writing about class, but I also abandoned the idea about writing a "class play" and just hoped it would happen. [Laughs.]

You were writing about people —

DLA: That's all.

And when you say you were aware of the class divide as a kid, you were aware because you went to a private school and the private-school kids let you know that you were a working-class kid?

DLA: No. I mean, it was more of my own making. It was just, they were incredibly different than I was. Their lives were different than mine. I mean, I was aware of class in the old neighborhood just because nobody really had anything in Southie, money-wise, and so I was aware of it then — but everybody was sort of in the same boat. But then when I went to Milton Academy, people dressed differently. People would go away on spring vacation and come back with tans, while I had spent two weeks watching television in Southie. Those sorts of things always were present: what they had and how they dressed and how I was different. The other kids at Milton didn't make me feel that way, but I was completely aware of it. It's not like I was the poor kid that got picked on. In fact, I was well-liked at Milton, and I was the funny kid, and so I was actually embraced. But still, I couldn't not think about how different they were.

Were you at Milton from junior-high through high school?

DLA: Yes, starting in seventh grade.

| |

|

|

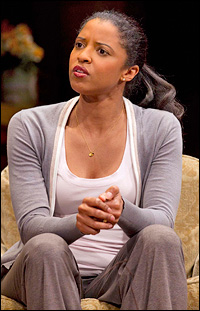

| Renee Elise Goldsberry | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

DLA: Well, certainly, yes. No question. If you're going to write about class, what better time than now, it seems?

There's a reference to a local factory in the play — an electronics factory? Gillette?

DLA: Gillette World Headquarters are in South Boston.

Gillette razors?

DLA: Gillette razors, yep. Shaving cream. Every Gillette product is made there. It's a huge factory on the Fort Point channel.

And a great employer of people from Southie?

DLA: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. This isn't in the play, but a friend of mine that I grew up with went to see the play last week, and she said, "Oh, you worked in Southie's Coal Mine." And I said, "What?" She was like, "Gillette! Southie's Coal Mine! That's what we called it." I was like, "Oh, my God, I totally forgot that." So they call it the Coal Mine. I wish I had remembered that; I would have put it into the play.

I had read that your mom worked in an electronics factory.

DLA: Oh, yeah, that was a different factory. Gillette. These workers are literally on the razor's edge.

DLA: That's it.

I wasn't sure if there was a connection to your mom.

DLA: No, my mom worked in a different factory. This isn't about my mom! You're crazy! It's Gillette! She worked in an electronics factory. [Laughs.]

I love how the idea of luck is so beautifully integrated into the lives of your characters. That they may be a missed-bus away from a greater opportunity, somehow. Are you aware of that in your own life — the randomness of things?

DLA: Yes. Yes, yes, yes, that's the thing that I'm most aware of in my life, in a way that the guy in the play [Mike, who rose out of Southie] is less aware of. In fact, he sort of shuts it out. I just think about so many things in my own life. The main thing is: I got a scholarship from The Boys Club when I was 11 to go to this private school, but this scholarship only came up once every six years, because it was a six-year scholarship. And so, I had to be the right age in the right year that it came up, and so just that randomness… And also, there were, at that time, three club houses in the city, one in Southie, one in Charlestown, one in Roxbury, and each clubhouse submitted two kids. So, I was one of six kids that were submitted for the scholarship, and I happened to be the one to win it. So, that whole thing. I mean, that's the biggest bit of luck. I think, "Gosh, if I wasn't 11 years old in 1980 or whatever it was, then I wouldn't have gone to Milton. What then?"

Gillette?

DLA: I don't know. Probably I'd be managing The Dollar Store.

Without the Boys Club, who would you be?

DLA: Who knows? I don't know. I hope not dead. I hope not in prison. But I look at a bunch of the people that I grew up with, and a lot of them have really terrific jobs and really wonderful families — and a lot of them are, in fact, dead and had drug overdoses and are in jail and all the awful things. And a lot of it is, they just went the wrong way or they didn't have the opportunity — or whatever that little hiccup is, they got the hiccup and I didn't.

| |

|

|

| Estelle Parsons | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

DLA: [Laughs.] Making fun of them, you mean? Well, Mike has gotten very good at passing, so he's used to the cheeses, but he still makes fun of them in that way. I've acclimated, but I'll never not be of the neighborhood. He's funny about the neighborhood; he's very different than I am. He romanticizes his past, but also wants to shut it out. I totally embrace the neighborhood and feel like it has made me who I am and totally defines me as a person, as a father, as a writer. It defines me in every way, and so, I own it, and that character, for whatever reason, romanticizes it but doesn't really own it. But he is of two worlds, and that is certainly true of me and has been true of me since I was 11. When I went out to that private school, I was a day student. And so, every day I would get on that train, and I would go to the suburbs and I would hang out with these rich people. I'm sure there were other scholarship kids, though we were less aware of it at the time, but [I hung out with] what felt like cultured and rich people, and then I would go back home and go to Southie. After a couple of years of that, I got a really terrific education, but I was less of the neighborhood — and yet, never really a part of that prep school. I had sort of a foot in both worlds, but never really belonging to either, and I think it put me in a unique position to be a writer, because of course, [I was] the outsider, right? Always the outsider. So, I think Mike and I have that in common.

There's a humanity to your characters, and a complexity. Mike and Margaret are complicated.

DLA: [Mike] has totally tried to recreate himself. He's moved up in class. There is something about marrying a black woman that feels like, "I am not that person that I used to be."

The bumps in his marriage seem directly related to him feeling pulled in several directions, would you say?

DLA: I would. There is an implication, I think, that he's probably had an affair or two —

With women who are not at his wife's level.

DL: Exactly. You are smart, yes. I would think so. If he is having flings with other women, I suspect they are probably not the highly educated, wealthy women that he may encounter in his life. Whether that has to do with the neighborhood…

The title really interests me; it prompts us to ask how people behave and what a good person is. Down deep, all of these people are incredibly good people.

DLA: Oh, thanks. I hope so.

Were there other titles?

DLA: In fact, there was one other title.

Can you share it or no?

DLA: Sure. It was briefly called Uncomfortable. … It doesn't slip fleetingly off the tongue. There is an exchange in the doctor's office when she says, "Mikey — you're rich!" And he says, "I'm not rich." And she's like, "Well, what are you, wealthy?" He says, "I'm comfortable." She says, "Oh, I guess that makes me uncomfortable, then." And so, there's the idea of comfort and being comforted and who's comfortable and who isn't comfortable and putting people in uncomfortable situations. It felt like, "Oh, that seems like a right title." I don't know, I didn't like the sound of it. It was a little too on-the-nose to me.

(Kenneth Jones is managing editor of Playbill.com. Write him at [email protected], or follow him on Twitter @PlaybillKenneth.)