*

Director Oskar Eustis is widely known for shepherding new works on both coasts (his invisible fingerprints are on such plays as Tony Kushner's Angels in America and Paula Vogel's The Long Christmas Ride Home). His latest directorial effort, a co-production between Yale Rep, Berkeley Rep and The Public Theater, is Rinne Groff's Compulsion, borrowing from a chapter in the career of Meyer Levin, the novelist and nonfiction writer who sought to get Anne Frank's diary published — and had a verbal agreement with Otto Frank (Anne's sole-survivor father) to be the adapter of a stage version of Anne's famous words. Starting in the 1950s, Levin was obsessed about making sure that the now-famous diary of a young girl reached as wide an audience as possible. And that the Jewishness of Anne's world be retained.

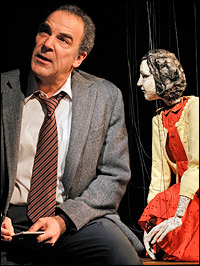

The diary became a bestseller in America partly because of Levin's advocacy. The authorship of Broadway's The Diary of Anne Frank, however, slipped from his hands, and the fictionalized Compulsion explores Levin's (or rather, Sid Silver's) singular passion over the injustice of it all — the snuffing out of the "authentic" Anne and the loss of his artistic hand in the project, to say nothing of the loss of potential income and fame (the play would win the Pulitzer Prize and the Tony and get a film version). Mandy Patinkin plays Sid with characteristic ferocity. His Sid Silver is at once a marching Ego and a moral hero, as the torchbearer of Anne's legacy. Patinkin, Eustis and Groff aren't interested in mere naturalism; their world is ripe with theatricality, offering song, puppetry, live voiceover, projections, actors doubling and tripling roles, and more. We spoke to Eustis, the Public's artistic director, in the days leading up to the Feb. 16 Public opening.

I love a good portrait of a monomaniac.

Oskar Eustis: [Laughs.] I wish I didn't feel so closely identified with him, but I understand the feeling.

Sid Silver really is single-minded, isn't he?

OE: Yeah. I mean, what I find extraordinary about him is, it's impossible to separate the degree to which he is, in a completely positive and heroic way, pursuing [a goal], and in what way he is, in a completely self-destructive, narcissistic way, lashing out because of a wound. And it's the fact that it's literally impossible to untangle those two impulses from each other that make him such a, I think, disturbing figure. And the "wound" is not, at least as I read it, about the fact that he's not getting a piece of the money or he's not getting a piece of the fame, but rather the wound of the diary's Jewishness being snuffed out by the publishing or producing world.

OE: That's exactly right. There's a sense in which his identification with his own Jewish identity is so deep that what he ultimately feels is that everything that's being done to de-Judaize Anne Frank is a direct personal assault on his own sense of self, and that ultimately the only way for him to retain his sense of who he is is to resist it with all of his strength, all of the time, which on the one hand, is completely understandable and even noble, and on the other hand, leads him into some terribly destructive and self-destructive things.

He alienates friends, colleagues, his wife….

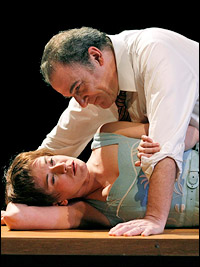

OE: Yeah, and not just alienates them, but damages them. We don't see the kids onstage, and that was a very deliberate choice, but you do see Mrs. Silver, and you just go, "At the end of the day, this woman has taken damage from this." It's, again, just a tremendously complex portrait, I think.

| |

|

|

| Mandy Patinkin in Compulsion. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

OE: That's absolutely right. Stockmann has been in my mind a lot; I think he's a very good analogy to Sid Silver. It's the same combination of egomania and idealism. Lear…? God wouldn't like it if I compared any playwright to Shakespeare… [Laughs.]

I do love the balance that you and Mandy created for Sid Silver: an obsessed man, a man of ideas, but also a lover — and a charmer.

OE: Yeah, though I have to say, the most important work I did on that was the day I cast Mandy Patinkin, because he's an amazing human being and one of the things that I feel comes through in his performance, as it comes through in life, is that the man doesn't have a mean bone in his body. Ultimately, everything he does, no matter how extreme, is coming out of love. And it's made him a fantastic colleague to work with through this last year. I've just loved [working with him], because at a certain point, when you've got a colleague like that, you'll throw yourself in front of a bus for them. You know that everything is coming from the purest of places, no matter how intense or extreme the process may get.

Was there a real sense of experimentation in the room with Mandy? I noticed at one point, in a transition, there's a snippet of a Yiddish song that he sings. I wondered if that was in the script.

OE: No, we made that up! [Laughs.] We actually made that one up in tech, when we were just playing a sound cue, and Mandy said, "Wow, I can take a note off of that sound cue." I said, "Well, maybe you should try singing something," and then he started singing. I said, "Oh, what is that?" And boom, boom, boom. In the rehearsal process, there's been a sort of joyous sense of invention, but the other thing that I like about Mandy is he's a dangerous performer, because genuinely, he takes risks every night onstage. There is nothing canned about him. There is nothing by rote about what Mandy does. He is alive onstage, and we have built in some real freedom in this performance, which means that every night I'm seeing new things. [Laughs.] Which I love, which I just love.

How did Compulsion first come to you? Did Rinne talk about it and did you know it from the beginning?

OE: The first time was on a very long car ride that Rinne and I had from Providence to New York, maybe seven years ago, when we were working on the first show of hers I did, Ruby Sunrise. And it was, in essence: "What else are you interested in working on?," and she started talking about Meyer Levin, and she had read about him over the years and was very interested in the subject, and we began a conversation. And I think the first things that actually went on paper, when she wrote something, were probably three years later. And I feel the great joy and privilege of having been in on this since before the beginning, and talking about it all along.

Were puppets and marionettes part of the experience from the beginning?

OE: Yes. I like to think that I may have indirectly influenced this just because the first show of mine that Rinne saw was a very heavy puppet show called The Long Christmas Ride Home.

A play that I love, yeah.

OE: Me, too. I did the premiere of that up at Trinity [Repertory Company] with [puppeteer] Basil Twist, and Rinne came up and saw it, and I sort of became puppet-intoxicated at that time. It wasn't immediate, but about two years into this discussion process, Rinne said, "I think Anne Frank should be played by a puppet," and I think what it did was liberate her to write Anne Frank, because we'd had a lot of conversations about: "Well, maybe it shouldn't be Anne Frank. Maybe it should just be a girl like Anne Frank." The problem is, nobody's like Anne Frank. She's an absolutely unique figure, and she felt very constrained in a piece that's about issues of representation and representing and who gets to speak for Anne Frank. I knew she just couldn't imagine casting an actress who would stand onstage and pretend to be Anne Frank. So when she thought of the puppet, it felt, to her, like an appropriate distancing device that then freed her to actually write in Anne Frank's voice. Then it led to a lot of other things, but it was a great idea.

| |

|

|

| Mandy Patinkin and Hannah Cabell in Compulsion. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

OE: Nope, that's completely correct. We actually found an article in TDR, an old TDR — The Drama Review. Alisa Solomon wrote a piece about Meyer Levin's marionette theatre. There are a bunch of pictures of Meyer Levin with his marionettes, including his production of The Hairy Ape, so all of that is totally real.

I'm curious to know what you learned — I don't like to say, "on the road," because this is a three-way not-for-profit co-production. But what did you learn in the previous productions?

OE: Well, you know, every step of the way, we kept refining. In Yale, we didn't even have video as part of it, and then video has, of course, since become a very significant part of the show. Between Berkeley and the Public, we changed our version of the Hackett [Diary of Anne Frank] play from one performed by puppets to one filmed in a toy theatre that our puppeteer created. And what I was thinking is that there's not any enormous change of direction that happened in the out-of-town productions, but what really happened was sort of a massive refinement of the means by which we tell the story. And ultimately, the thing, I think, that's most important is, I feel like we found the ending. We didn't really find that until very near the end in Berkeley: How we could balance the admiration for Sid Silver with the judgment of Sid Silver, which I really think, at the end of the day, is the trick in the play, which is, "How are you to judge this man?" To figure out how we can get the right balance between condemning and understanding was very difficult, and I feel quite good about where we are now.

You're aware of Meyer Levin's background. How much did you have to say, "I need to put the reality or the truth of Meyer Levin aside and just follow the script?" Were you digging, digging, digging into history?

OE: Sure, I was — while I was the dramaturg. [Laughs.] In other words, while we were working on the script, I went through the history like nobody's business, and I've read, probably, eight or nine of Meyer's books at this point. I've gotten to know his son. We did a lot of work, but I think the success of the play, for me, is measured by the fact that once Rinne had the play written, we don't have to refer to history at all, because the fictional world that she's created, which has incorporated the history, has got its own integrity strongly enough so that the only thing we're really asking is, "How do we follow through on the true consequences of this story…?" So, it's actually been a perfect relationship for me of history to fiction. The history is the soil from which it sprang, but it has its own integrity.

| |

|

|

| Mandy Patinkin in Compulsion. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

OE: Well, it's hard for me to say if it's an Oskar Eustis aesthetic. It's certainly what I like. It's what I like to do. I am a guy who really believes in narrative. I really believe that storytelling and empathy are at the key of what the theatre provides, which makes me kind of old-fashioned. But at the same time, I am enough a man of our times to recognize that naturalism doesn't work for us most of the time. We can't pretend we're not in a theatre. We can't somehow go backwards to a time, maybe, before the Modernist Revolution, when we understood that the means of telling the story are part of the story itself. I'm constantly thinking: "How do we tell this story that makes the story powerful, without asking the audience to pretend or ignore the fact that they're in the theatre?," because that, I think, actually undermines the power of what we do. I know your passion is for new works. In a job where you have to shake so many hands and you have juggle administrative stuff, is the greatest joy of the job still new work? What's the joy you find?

OE: Honestly, it's always going to be my greatest joy. There is nothing I would rather do than be talking to a playwright about pages that are still warm in my hand because they've just come off the printer. I just got off the phone with [Tony] Kushner. … There's a new scene for [The Intelligent Homosexual's Guide to Capitalism and Socialism with a Key to the Scriptures] that is brilliant! Years into this, he's cracked something, and to be able to talk to him about that and go — there's nothing I enjoy more than that.

(Kenneth Jones is managing editor of Playbill.com. Write him at [email protected]. Follow him on twitter @PlaybillKenneth.)