*

We all know what Oskar Eustis, artistic director of The Public Theater, refers to as Shakespeare's so-called "golden dozen": that roster of plays (Hamlet, Twelfth Night, King Lear, A Midsummer Night's Dream and so on) that get done time and again, leaving the less celebrated works of the canon to languish relatively unexplored.

Until recently, that is. Cymbeline is a late-career Romance that seems to have come back into fashion, as has the knotted, bitter, endlessly fascinating Troilus and Cressida, one of a trio of acknowledged "problem plays." This summer, The Public Theater's Shakespeare in the Park is giving itself over entirely to two other such plays that ostensibly end happily, but who's to say? Running in repertory through July 30, Measure for Measure and All's Well That Ends Well share the Delacorte stage; an ensemble of actors that includes John Cullum, Tonya Pinkins, Reg Rogers, Annie Parisse, and Michael Hayden; and a view of humankind that at once troubles and intrigues. And since we live in confused times, why not relish plays that unapologetically lend confusion pride of place? "All yet seems well," we're told at the climax of a play whose title itself is subject to revision by the end of the fifth act.

Eustis points up a desire "to tackle the thornier plays in the repertoire and to tackle them in the Park" — plays, he says, that offer up "real challenges of unity and tone." Sure, All's Well concludes with the orphaned Helena, ward of the elegant Countess of Rousillion, finally coming together with Bertram, who is both the Countess's son and the object of the lowly Helena's abiding lust. But does their commingling prompt the cause for celebration that we take away from, say, Rosalind and Orlando or Beatrice and Benedict? Possibly not, in the same way that one casts severe doubts over the amorous appropriation in Measure for Measure by the Viennese Duke of the young novitiate nun, Isabella. Even that play's erotically awakened Angelo is an anti-hero from whose advances we recoil in a mixture of fear and disgust; some figure of authority he, though modern-day equivalents are, alas, all too easy to find.

| |

|

|

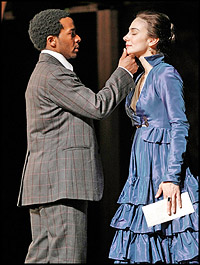

| Andre Holland and Annie Parisse in All's Well That Ends Well | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

Daniel Sullivan triumphed in the Park last summer — and scored a Tony nomination — directing a Shakespeare "comedy," The Merchant of Venice, that registers very darkly, to put it mildly, in the modern day. All the more reason for his return a year later, this time with a play in which class proves the potentially insuperable issue just as religion is in the money-minded Italy on view in Merchant. "Trying to solve the problem of a play like this is why you go into it," explains Sullivan, whose task includes tracing the trajectory of the aristocratic Bertram and the physician's daughter, Helena, so that their eventual union makes some kind of sense.

| |

|

|

| Tonya Pinkins and Carson Elrod in Measure for Measure | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

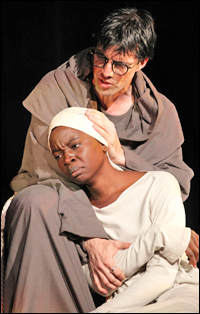

Justice itself is put on trial in Measure for Measure, one of the few Shakespeares whose title figures resonantly in the play itself (All's Well is another, its titular aphorism amended, as mentioned, in time for the final bows). Barry Edelstein, director of the Public's Shakespeare Initiative and dramaturg for both productions, talks persuasively of Measure bridging the legalistic milieu of Merchant with the sense of stage managing the event that we associate with late plays like The Tempest: not just a "problem play," in other words, but a pivotal one.

Measure, notes Edelstein, "brings in Christian doctrine and spirituality to provide a framework in which we can understand the qualities of mercy, whereas All's Well is a completely secular play." But like its Delacorte counterpart, Measure remains discomfiting in its move toward a final alliance that can seem mighty cryptic, not least when confronted with the travails suffered by the righteous Isabella at the hands of the craven Angelo. The rampant libido of the Duke's appointed deputy itself contributes to a play that, like All's Well, separates out love from sex. Such comic heroines as Twelfth Night's Viola, one feels, would be appalled.

| |

|

|

| Lorenzo Pisoni and Danai Gurira in Measure for Measure | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

*

Matt Wolf is a London theatre critic for The International Herald Tribune and a founding member of the website

www.theartsdesk.com.