*

"The Hammersteins: A Musical Theatre Family" by Oscar Andrew Hammerstein [Black Dog and Leventhal]

"The Hammersteins: A Musical Theatre Family" is two books in one, the first about Times Square pioneer Oscar Hammerstein I and the second about musical theatre pioneer Oscar Hammerstein II. The first book is engrossing, recreating the many worlds within which Oscar I and his two sons operated. Here we have a fine portrait of Oscar II's grandfather, who arrived in Manhattan as a penniless teenager in the midst of the Civil War and started his career rolling cigars. The second part, though, is a pale and perfunctory snapshot of Oscar II, coming from his grandson Oscar III.

There is a provocative quote from Oscar II, relating how he sat for four minutes by Oscar I's bed as he lay dying in 1919 — "the longest time I ever spent with him." Oscar II had lived 24 years in fear and resentment of his internationally famous namesake, unable to even talk to the man. Here, in "The Hammersteins," we have Oscar II's grandson and namesake telling us the story of his grandfather. What has he to say?

Nothing. Did Oscar III spend five minutes with Oscar II on his deathbed? Did he grow up in fear and resentment of his grandfather? Was he even born when Oscar II died in 1960? Doesn't say. The author doesn't even tell us that he is the son of James, Oscar II's younger son. (This information can be gleaned from the dedication "to my dad, Jamey.") Nor does he identify himself as Oscar Hammerstein III, although he has been described elsewhere in that manner.

|

||

| Oscar Hammerstein II |

|

||

| Oscar Hammerstein I |

||

| photo courtesy Library of Congress |

Typos are one thing; everybody makes typos, myself most certainly included. But the Oscar II section is filled with the kind of mistakes that don't seem to be careless typos; just incorrect statements that even a casually knowledgeable fan of Hammerstein's might pick up. And the danger is, some unsuspecting young student of theatre might come along, read this book, and take these statements as fact. This sloppiness extends to the photo captions, the first of which — "Times Square at night" — is all too clearly a shot of Hammerstein's Theatre (now the Ed Sullivan), a good half-mile from Times Square.

All of which makes "The Hammersteins" perplexing. The first half is, to borrow from Oscar II, something wonderful. Oscar I's life has previously been discussed at length in several places, but Oscar III for the first time pulls all the strings together and makes sense of this fascinating man. When he went bankrupt the first time, his competitors banded together and raised $25,000 for him. How many businessmen in a cutthroat profession would do such a thing as that? Truth to tell, the Oscar I chapters make "The Hammersteins" a worthwhile read. But oh, what a portrait of Oscar II by his grandson could — and perhaps should — have been.

|

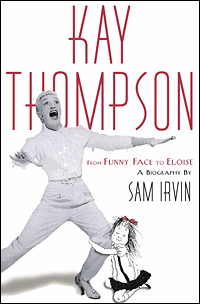

For those of us born on the later side of 1950, the name Kay Thompson mysteriously turns up from time to time (as in the tribute goddaughter Liza Minnelli recently brought to the Palace). Less young readers might remember her when she was in still active, but we don't. Sam Irvin, who last fall gave us "Think Pink!" [Sepia 1135], a three-CD compilation of her recordings and performances, has written the first full biography of Ms. Thompson (1909-1998). Actually, this seems to be the first accurate anything about her; Thompson reinvented herself many times over, with little interest in biographical accuracy. What we discover is that Thompson — Kitty Fink, a pawnbroker's daughter from St. Louis — had no less than five full-blown careers. She started out as a distinctive and at times highly successful radio singer and arranger, working in Los Angeles, New York and elsewhere. In this guise she made it to Broadway, or nearly so, in 1939; she was fired in Boston from a major role in what would turn out to be her only Broadway musical, Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg's Ed Wynn vehicle Hooray for What?. She maneuvered herself into an arranging and coaching job at M-G-M in 1943, becoming an all-important cog in that studio's Arthur Freed unit — the one that turned out all those golden musicals.

That type of gold dried up in 1947, so Thompson did not renew her contract and put together a grand nightclub act. Kay Thompson and the Williams Brothers was apparently an act unlike anyone had seen before, or perhaps since, literally drawing West Coast audiences to the newly-established Las Vegas. Thompson virtually set her own price in top clubs in America, Paris, London and elsewhere. Soon enough, the novelty of that career began to wear off — hastened by competition from top-name celebrities who followed Thompson's example. Career four was brief; Thompson went back to Hollywood as an actress, co-starring with no less than Fred Astaire and Audrey Hepburn in the 1957 motion picture "Funny Face." Thompson is simply wonderful in that film; her "Think Pink" number is iconic and if you haven't ever seen it, drop what you're doing and find it on YouTube. You could even make a case that she managed to steal the movie from the illustrious Fred and Audrey, which was quite a feat. But Thompson never did follow up her success with another film. Her fifth career, as an authoress, started simultaneously with a bang and a clang: "Eloise" was the fifth highest-selling fiction book of 1956 — and this was a kid's book! Eloise and Thompson moved into the Plaza, from which they ran an Eloise empire with sequels, merchandising and more. But that didn't last long, either. Then came a long decline, with Thompson cloistered away the rest of her years as permanent houseguest to Ms. Minnelli.

With Mr. Irvin as our guide, we see that Thompson really did attain several levels of fame. We also see that the lady was something of a monster; Irvin doesn't quite label her as egotistical, grandiose and graspingly greedy, but that's what comes across. Which is why each career starts, builds and mystifyingly ceases. That and various addictions, including many years as a patient of Max Jacobson (AKA Dr. Feelgood). Over the years we have heard about him, too, in various books. Irvin is the only author I've come across, though, who tracks down Jacobson's daughter for an interview. That's the kind of book "Kay Thompson: From "Funny Face" to Eloise" is. Comprehensive, yes; it seems like Mr. Irvin discusses every song Thompson ever sang, starting when she was six. But could we truly understand this ridiculously complicated whirlwind without all these details?

*

AND ON THE MUSIC SHELF

|

This is fine for rehearsal pianists, but wouldn't you rather play Sondheim's version — with his arrangements and actual harmonies — than some editor's reduction of the orchestrator's translation of the original? The Sunday in the Park and Into the Woods vocal scores were prepared using Sondheim's own piano manuscripts, and Sweeney Todd has already been updated in this manner. Now they are joined by the corrected and Sondheim-approved Little Night Music. And lest you wonder, a note on the title page instructs us that "insofar as discrepancies in the lyrics, this vocal score is to be considered correct." It is gratifying to learn that the folks at Hal Leonard take their stewardship of Sondheim's work so very conscientiously, and have a program in place that promises more of the same.

Hal Leonard has also released an Addams Family songbook. Two Addams Family songbooks, actually: the traditional "vocal selections" and what they call "piano/vocal selections" (with the melody in the piano part). Thirteen songs by Andrew Lippa, plus Vic Mizzy's "The Addams Family Theme" complete with finger snaps. Also available is a new edition of the vocal selections book for Promises, Promises. Twelve songs by Bacharach & David, including the two songs — "I Say a Little Prayer," "A House Is Not a Home" — that were added for Kristin Chenoweth to sing in the current revival.

(Steven Suskin is author of the recently released updated and expanded Fourth Edition of "Show Tunes" as well as "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," "Second Act Trouble," and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He also writes Playbill.com's popular DVD Shelf and On the Record columns. He can be reached at [email protected].)

*

Passionate about theatre books? See what the Playbill Store has on its shelves.