*

Few things in life are as head-clearing, as soul-soothing, as some free Shakespeare at sunset in the summertime. New Yorkers have partaken of this urban "vespers therapy" since June 18, 1962, when The Public Theater set up permanent summer residency in Central Park, opening its Delacorte Theater with a production of The Merchant of Venice, directed by The Public's visionary Joseph Papp and starring George C. Scott.

Bernard Gersten, now executive producer of Lincoln Center Theater and then associate producer of the New York Shakespeare Festival, remembers it well — even poetically: "I have a vivid memory of a moment in the first act when George Scott was holding the scarf of his daughter who'd just run off with that Gentile, and he was saying something like, 'My daughter! My jewel!' He held the scarf up, and a breeze took it and wafted it around the stage. It was extraordinary — a really spiritual thing!"

| |

|

|

| George C. Scott in The Merchant of Venice, 1962. | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

A great civic free-for-all developed over making Shakespeare free for all, with Papp standing his ground against NYC "master builder" Robert Moses, who felt charges should be made for lawn-upkeep. "They came up with all sorts of stuff — bothering the squirrels . . . ," cracked Merle Debuskey, Papp's media-savvy publicist from the mid-'50s to 1990. He took the argument to the press, where it became a case of David-versus-Goliath. Along the way, critic Walter Kerr suggested in print a compromise: "Joe, charge a quarter. What's that?" Papp was pondering that possibility when his publicist, famously, put things in proper perspective: "Joe, I'll work for Free Shakespeare for nothing, but I won't work for two-bit Shakespeare."

| |

|

|

| Oskar Eustis | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

"It was Joe's idea of free access to Shakespeare for both audiences and actors — I think he had it forever, and he hoped it would go on forever," says his widow, Gail Merrifield Papp. "The Delacorte came into being with that idea, through a series of stages, starting in a church on the Lower East Side where he began doing free Shakespeare and then moving into the parks and on to the biggest park of them all, Central Park. After a few years, he realized that he wanted to have a permanent stage there — he was performing on a platform, and the audiences had grown so large they needed a different kind of accommodation than fold-up seats — so that was the idea that propelled it. I'm still in awe of the strength of his idea. One, it's free, which means you have democratic audiences, and then you have — from earliest time, way in advance of other kinds of theatres — democratic accessibility for actors so that Shakespeare reflected the American population and its energy. That really hadn't been too much the case before. He linked this to high artistic standards so there was a kind of energy to that, along with the pioneering relationship to the city.

"Three generations of actors and audiences have now been engaged in it, and I'm delighted how vital and alive the idea still remains. The argument for it, even after 50 years, retains its youthful vigor and urgency on the part of everybody concerned — audiences and actors and directors. You can't talk that into existence. It's just there. Oskar Eustis feels it. His presence enhances it and fortifies it."

Eustis' first brush with the Delacorte was actually a brush-off. "I auditioned for Joe for a role in his 1976 Henry V, and he didn't cast me. It was actually the last time I auditioned. I walked out of that audition and said, 'I'm never auditioning again.'"

And he didn't either, finding instead a useful niche behind the footlights that has ripened, over 36 years, to Papp-like proportions. Now, he is The Public artistic director, cracking the whip over the Delacorte's 50th anniversary season, which turns out to be one-part Shakespeare (As You Like It) and one-part Sondheim (Into the Woods).

| |

|

|

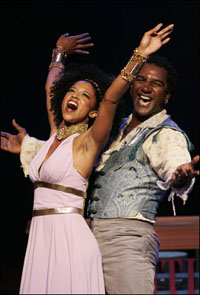

| Renee Elise Goldsberry and Norm Lewis in Two Gentlemen of Verona. | ||

| photo by Michal Daniel |

Most of his Delacorte memories have to do with the weather. "One night I tried to stop Mother Courage because it was raining so hard, but the actors wouldn't let me do it. Kevin and Meryl and the others just refused to stop performing. Meryl got out and mopped the stage. The audience cheered for her. The sight of her, by herself, pulling that wagon in a circle in the rain, close to midnight, in Central Park, won't go away. At the end, there was an ovation like you never heard. Of course, the audience was not only cheering the show but cheering everybody for not going home."

Then, there were the teasing flashes of lightning that tensed up the Hair opening and erupted into a deluge in the homestretch when "Let the sunshine in" was uttered.

He chose to celebrate his 50th birthday with Hair at the Delacorte. "At the end of it, when I was dancing on stage as I usually did, the cast suddenly picked me up and led the entire audience in singing 'Happy birthday.' It was probably the happiest moment of my life.

"But then, every evening of Hair was magical to me," says Eustis — and that includes the night the Clintons came. "It was shortly after Obama had beaten Hillary for the nomination. When she and Bill and Chelsea walked into the theatre, she got a standing ovation from the audience. You could really feel New York was welcoming her. I sat with them for the show, and I can promise you our Secretary of State knows every word of every song of Hair, including 'Gliddy glub gloopy nibby nabby noopy / La la la, lo lo / Sabba sibbi sabba nooby aba naba / Lee lee lo lo.'"

| |

|

|

| Al Pacino in The Merchant of Venice. | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

"Al Pacino had not done the park before he did Merchant," Eustis notes. "We went out together to the Delacorte one cold, rainy spring day, and he was, like, 'Oh, I'm not going to be able to go on if it's like this.' As it turned out, Al was not only a trouper, he loved doing it. Over and over, there's something about the elemental nature of the park that is a challenge — but an attractive challenge. Even more, the actors love what the audiences like. It's such a beautifully appreciative audience, precisely because they haven't paid $400 for a ticket. They're there for free, they've waited in line, and they're there to love it!

"I have never had an actor actually complain to me about conditions in the park when they're doing the show. When they're imagining it, they sometimes get scared about it. Then they do it and discover the joy of contending with those elements. This is as true of Meryl Streep as it is of Anne Hathaway."

Eustis would just as soon skip the stories about bugs flying into the mouths of actors in mid-soliloquy and concentrate on the raccoon ruckus. "There has been many a raccoon that has decided to mate at inappropriate moments. Everyone who works at the Delacorte becomes familiar with the sound of raccoons being amorous. It's not a pleasant sound. It does not sound like anybody is giving consent to anything."

What Mrs. Papp loves most about Delacorte audiences is how they respond: "in a way that's not been affected by high ticket prices, which encourages a kind of aloofness. I think it's curious to say this, but the relationship of actors and audiences there are more like that of Shakespeare's day where there's a kind of immediacy and reciprocal understanding. You can hardly find that anywhere else in the theatre. "In a way, I feel that the Delacorte gave birth to The Public Theater because Joe thought contemporary playwrights could learn a lot from Shakespeare. He liked to ask people, 'OK, what's the first line of Hamlet?' Usually, people didn't know. Well, it's 'Who's there?' That's a good way to start a play, and Shakespeare knew how to do it, so he thought playwrights could learn for being closer to Shakespeare. He used to cite the Royal Shakespeare Company after he visited them in the early '60s and saw classics alongside new works — how they really complemented each other and gave each other new kinds of energy. He had that very strongly in mind when he decided to build a permanent theatre."

View production photos from 50 years of Shakespeare in the Park at the Delacorte: