*

The pulse-quickening dialogue in an Aaron Sorkin drama hurtles at you like a blazing Roger Federer forehand. Whether it's his breakthrough stage-to-screen work A Few Good Men, his landmark television series "The West Wing," his Oscar-winning film "The Social Network," or his divisive new HBO drama "The Newsroom," Sorkin delivers whip-smart verbal volleying and rousing arias on journalism, politics, pop culture and human relations that is at once crackling, caustic, stylish and thought-provoking.

And who better than Jeff Daniels — as the brilliant, arrogant and irascible cable news anchor Will McAvoy — to deliver that quicksilver banter? After all, Daniels has made acerbic erudition and droll verbosity a hallmark of his recent roles. There was the sardonic blind sidekick Lewis in "The Lookout," the mercurial self-help author and bitter recluse Arlen Faber in "The Answer Man," and the pompous, cell-phone-wielding corporate lawyer with dreadful parenting skills in God of Carnage on Broadway. The high water mark was Daniels' tour-de-force turn in Noah Baumbach's family divorce drama "The Squid and the Whale," in which he imbued the epically narcissistic blowhard Bernard Berkman with a ramshackle pathos.

In the opening episode of "The Newsroom" on June 24, Daniels' cable news host Will McAvoy — mocked as a blandly inoffensive Jay Leno news figure obsessed with his likeability and protective of his own political views — shocks his constituents at a journalism school panel with a "Network"-style meltdown, reminiscent of Howard Beale's infamous "I'm mad as hell" rant in that picture. Responding to a question by a naïve young college student who asks why America is the greatest country in the world, Will launches into a fact-and-figure-filled harangue about why that's absolutely not true anymore, but insisting that America can once again return to its faded glory days. His diatribe is captured by cell-phone cameras in the auditorium, and the video quickly goes viral.

After Will returns from a weeks-long exile, he learns that his boss Charlie (Sam Waterston) has hired a hotshot new executive producer for "News Night," MacKenzie McHale (Emily Mortimer), who just happens to be Will's ex-girlfriend. MacKenzie, with Charlie's backing, implores Will to seize the moment and revamps "News Night" into a program whose primary concern is giving viewers information that they can use in the voting booth — which means putting facts at the center of the show, ignoring ratings, and avoiding sensationalistic stories like the Casey Anthony trial or human interest fluff. "There's nothing that's more important in a democracy than a well-informed electorate," MacKenzie tells Will.

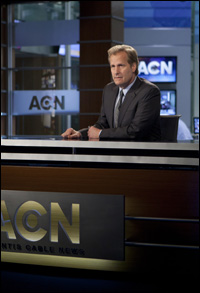

|

||

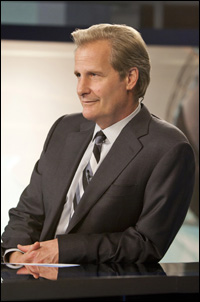

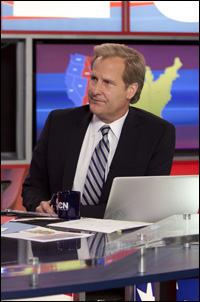

| Daniels on "The Newsroom." |

||

| photo by Melissa Moseley |

The critical reaction to "The Newsroom" has been polarizing. It's been decried as sanctimonious and self-righteous — that the characters are talking at each other and at the audience. In the second episode, Thomas Sadoski's Don says to Alison Pill's Maggie that what MacKenzie and Will are trying to do with "News Night," won't work. "Nobody's going to watch a classroom," he says. "They'll either be bored or infuriated." Which pretty much sums up some of the negative early critiques of the show. Sorkin has also come under fire for his problematic writing of female characters. One Slate critic admonished the show for being "a sexist mess, where the women are neurotic, tech-incompetent emotional morons who snap into professionalism just in time to make the men they bolster look good."

Other prominent voices have come to the show's defense, including The New Yorker's David Denby and legendary former CBS news anchor Dan Rather, who wrote (on Gawker!) that "The Newsroom," "gets close to the bone of what happens, what really happens, behind the scenes in newsrooms and the boardrooms that govern them."

Despite divisive reviews, the ratings have been a bright spot, and HBO has already renewed the series for a second season.

Calling from his home in Chelsea, Michigan, where he's spending the summer, Daniels discussed Sorkin's musical way with words, the contentious reaction to the show, his sideline career as a playwright and theatre impresario (he founded the popular Michigan Equity theatre Purple Rose Theatre Company), and how James Gandolfini helped him navigate his first television series gig after more than 50 films.

What about Will's transformation really appealed to you? Why did you want to play this guy?

Jeff Daniels: Once that opening speech was written, you could just see that telling the truth has consequences. There's nothing in that speech that isn't true. And you may not like it, it may disturb people who watch it, it may seem to some unpatriotic. But nothing that Will says when he goes off is not true. It's all true. And you could tell that that was going to trigger not only a complete change in the guy, but also consequences. This was not going to be an easy ride. It seemed to be such an original speech that hit people right between the eyes. I know it felt that way when I performed it. And you can tell by some of the reaction we've gotten since it aired. They either love it or hate it. Aaron writes compelling characters in that he throws up these obstacles and he ups the stakes, like any good writer does, and he sends the characters crashing into things. Aaron also writes big ideas — and Will is a big idea. It's not an accident [Aaron] hose the Don Quixote and Man of La Mancha references to "The Impossible Dream." In a way they are trying to do the impossible dream — by doing a newscast that is very difficult to do now.

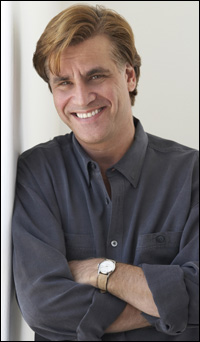

|

||

| Aaron Sorkin |

||

| Photo by John Russo |

JD: We did a screening in New York the week before the show premiered, and all of the New York media and cable news people were there — people from "60 Minutes" and producers from CNN and MSNBC. I talked to a couple of 'em, and one of them said, "I hope that the show deals with those of us who are trying to hang on to the ideals of journalism and just doesn't attack the whole industry in a general sense — that we're all a bunch of idiots who are covering the Kardashians." I think the show does try to hang on to those ideals of journalism. It was interesting to see and to hear these guys say, "We fight that fight every day." They're constantly going up against the ratings. If they should continue to cover a certain scandalous story, their ratings will rise. Or if they move away from that story, their ratings will drop. It's this push-pull thing they have with advertisers and corporate. So that's what Will and MacKenzie go up against. They try to do "Nothing but the truth, here we come." And it costs them ratings, and Will's job becomes in jeopardy.

One of the show's critiques is that the media is obsessed with fairness and balance. As MacKenzie and Will articulate, some news media have a bias toward fairness, but that there isn't always two sides to every argument — and sometimes you have to call out a ridiculous argument as exactly that. Do you think that's a valid criticism?

JD: I see Aaron's point on that. MacKenzie says, you know, sometimes there is only one side to a story, and sometimes there are five. And then Will makes that reference to leaning so hard the other way as to appear fair and balanced. I don't know, I don't think about that as much. I'm more focused on the cable news guys — how the left stays on the left, and the right stays on the right. That's what I see. As Will said last week: Let's cut through the spin. Let's cut through the marketing. Let's cut through the branding. Let's cut through the talking points. Let's give these people not only the facts, but as we say often in the series, "the two best competing arguments," and then let the viewer decide. Too often we're just given talking points from a guest or an interview or segment of a political party. We have a line later on in the season where I just throw up my hands and go, "Why can't we call a lie a lie when we know it's a lie?" We start to [do that], and that gets us in trouble.

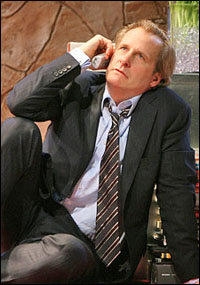

|

||

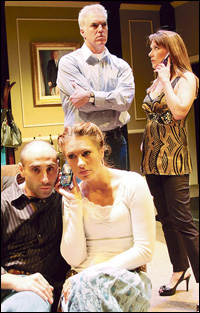

| Daniels in God of Carnage. |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

JD: Yeah. I guess so. I hadn't thought about that. I was thinking more about the fact that, you know, I am one of those angry Americans who's been dissatisfied with both sides of the aisle — and government, to be honest. I mean, there are people doing good things and trying to do good things. But I get angrier and angrier at the corruption, the look-the-other-way attitude, and the political environment in Washington. There are a lot of people out there who care and want the people in Washington to do better. So that's this character. It's all in that opening speech. It just spoke to me. There was no research necessary.

There's lots of great theatre talent working on the show — John Gallagher, Jr., Alison Pill, Thomas Sadoski and Sam Waterston. Do you think actors with lots of theatre experience have a particular facility for speaking Sorkin's dialogue?

JD: They did a smart thing. They hired a lot of theatre people. We're used to a lot of words. We're used to being off-book and just knowing it. And that came in handy because it really is like doing a new play every two weeks. It really helped with the memorization. Sometimes you'll do movies and TV shows, and people will just be looking at the script that morning. You can't do that with Aaron. Very quickly, that became the drill: Know the script, and know what you're going to do with it when you get there in the morning. With Aaron, you memorize every word. There's nothing that's ad-libbed on the show. And, to theatre people, we don't even blink at that, because that's what the theatre is. You memorize what the playwright writes, and that's it. Whereas, in Hollywood, sometimes the actors think that they're the writers and try to come in and change everything, which is one of the courses they teach in Star School.

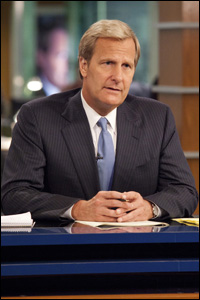

|

||

| Daniels on "The Newsroom." |

||

| Photo by John P. Johnson |

JD: The whole trick with Aaron is to get ahead of him. You can't be playing catch-up. The dialogue is so intricate and musical, just like a play. Once you start working on a play, there's a music to it. The great writers all write with a rhythm — all the way back to Shakespeare. Mamet certainly does. Lanford [Wilson] did. And Aaron is the same way. That's why you memorize every single word, because there's a rhythm to it. Then with Sorkin, because you're going at what seems like a hundred miles an hour, you don't have time to kind of pause and stutter your way through a line as you try to remember it. You've got to know it so well that you can get on top of it and dance on top of it — so that you can give different inflections, different speeds, add different spins on it. You do it a whole bunch of ways, so that they have some options in the editing room. But you can't give them options if you don't know it. Let me say this: I brought my golf clubs to California, and they never left the apartment. You spend the weekend sleeping and memorizing. A long answer, but it gets to what theatre people all know, which is getting the dialogue cemented in your head, so it feels like the 100th performance of a play. That's a whole different settling in — when you know it, you own it, you don't worry about it.

|

||

| Alison Pill on "The Newsroom." |

||

| photo by Melissa Moseley |

JD: Yeah. I don't think an episode goes by without a reference to some Broadway musical or musical theatre. We're kind of always going, "Oh, here's another one!" We cover quite a few of them in the course of the first season: Brigadoon, Camelot, Oklahoma!, Man of La Mancha, Annie Get Your Gun.

At first, Will comes across as a pompous, irascible jerk. But we start to see the cracks in the facade and glimpses of a more vulnerable and self-loathing side to him. How will the character change over the course of the season?

JD: Well, they will see him try. The trick to playing an unlikable character is, you know, don't try to make him likable. But just maybe if you're lucky, the audience will understand what he's going through. Sometimes that takes time. I think over the course of the series, he still is who he is. He still feels betrayed and feels that way deeply, and MacKenzie is the cause. A lot of his friends are on the other side of that camera, and that's a lonely place to be when those are your friends. And MacKenzie is a woman who he is still madly in love with, and at the same time he hates her guts, because of what she did. He got hurt. And he tries to find a way to make it okay, to forgive her, to get over his own anger and issues, so that he can work with her and maybe even be with her again. That struggle is a lot of what this first season is about — for both of them. There's been so much damage done to the point that there is no going back. Yet here they are, thrown together in a work situation. That's what Sorkin does. He creates this impossible situation. Despite everything that's happened between them, they now have to work together every day.

|

||

| Daniels on "The Newsroom." |

||

| Photo by Melissa Moseley |

JD: Y'think?

Just a little. Some people like it, and others loathe it. The negative reviews have been sharply critical of what they see as a sanctimonious and self-righteous tone, that there's too much speechifying and pontificating. Or that Sorkin is injecting his own politics into it. What is your response to those critiques?

JD: Well, like a lot of actors, I stopped reading reviews years ago. I really have. Good or bad. My wife collects 'em, and if there's something incredibly great, then go ahead and read me that passage. But other than that, hit the delete button. Look, they're talking about the show. So that's a good thing. Love it, hate it, I could care less. They're talking about the show, and that's good. And you know, art is supposed to leave people talking about it. You're supposed to walk away from whatever art you've just witnessed, and it's supposed to stay with you. So I'll take that. If you loathe it, okay. But at least we're still engaging you, we're still pissing you off. I think part of the problem with Aaron's stuff is that — and he'll tell you this… He goes, "I like seeing things that I know were written." So he admits to writing a heightened, stylized kind of dialogue. Our job is to make it look like it's falling out of smart people's heads the moment they think of it. Now, you can either buy that or not. If you don't buy it, then don't watch. As far as the critics go, they're not writing for us. It took a long time to learn that. You certainly hope they like it. But they're writing for their readers. They're writing whether you should see it or not, whether you should spend your money on it. That's different than an acting critique. If Meryl Streep writes a review, then I'll pay attention. Not to be disparaging to critics. That's their job — to like things and not like things.

Do you think the show has come under more scrutiny and taken such a beating in the press because it's about the media and the news business itself?

JD: Well, there are a couple of expressions. One is: We are knocking at the temple door. And I don't know if this applies, but in movies, you know, you never shit in your own front yard. It seems to me that it's probably hitting a little close to home — for some, not all. What's been interesting, though, is the missives that have flying back and forth amongst the different critics and media people. [The New Yorker television critic] Emily Nussbaum goes on a nut about it. Then [New Yorker film critic] David Denby goes after Emily Nussbaum. And here comes Dan Rather. Then David Carr in the New York Times writes a piece bringing CNN into it. People are talking about it and discussing it. And anybody who's ever spent any time in this business knows that you cannot and will not please everyone. But we found a need and we hit a nerve all at the same time.

|

||

| Daniels on "The Newsroom." |

||

| Photo by Melissa Moseley |

JD: I did it for a lot of reasons, personally. But I really wanted to create a Circle Rep of the Midwest or what I remember of Circle Rep [the famed New York theatre company where Daniels first got his start in the 1970s]. We were certainly looking to theatres like Steppenwolf and people who had already started doing that kind of thing. I wanted to see if I could do it in southeastern Michigan, in the middle of corn fields. To gather a company of professionals from around here, meaning actors, directors, designers, and then to get playwrights writing. But finding writers and turning them into playwrights takes time. You've got to develop them and show them that you're going to produce their stuff while they get better. Then doing new plays. That's what Lanford [Wilson] and [director] Marshall [Mason] taught me at Circle Rep. That's all they did were new plays. So I was interested in all of that — blindly so. And we had a lot of peaks and valleys, swings and misses. But we gained a consistency in the second decade that we've been able to maintain. The production level became very high, and we built an audience. I mean, who knew whether anyone would come after the first year? What the art of theatre has done for this community, you can see it in the faces of the people. You can see it in the minds that have been changed — in the artists and also in the audience. That's been the most gratifying thing: To see that theatre can still make a difference. I think Marsha Norman said that good theatre can change lives, and the Purple Rose has proven that. You've written 14 plays for the Purple Rose so far. And you're going to be premiering a new comedy The Meaning of Almost Everything at the theatre in January. What's that all about?

JD: It's about a guy who really doesn't want to participate in time. He'd just prefer to stay in this one moment — right here, right now. That moment — the one that just passed. He wants to be in that moment forever. So he's just going to do that. Then another guy shows up and says, "Well, that's not how life works. That's not how time works. You have to go to the next moment. You have to live on." And the guy says, "Nope. No, I don't. I refuse to participate." So it's this struggle of…well, people have written paragraphs about it, but the duality of man, hanging on to each and every moment and resisting death. It covers everything. That's why it's called The Meaning of Almost Everything. [Laughs.]

|

||

| Matthew David, Rhiannon Ragland, Alex Leydenfrost and Michelle Mountain in the Purple Rose Theatre production of Best Friends, a play by Daniels |

JD: Yeah. It just seemed to fit. As if someone could know everything. It's very funny. They go to great lengths to prove each side of that argument. It's a bit vaudevillian, a bit Abbott and Costello. There's an archness to the dialogue. Let's just say that the thesaurus was smoking.

Your three-decade-plus career encompasses more than 60 films and TV movies. But "The Newsroom" marks your first foray as a regular on a television series. What's that been like doing series television for the first time?

JD: Well, ever since I did "The Squid and the Whale," I've been chasing writing. I just want to find good writing and go do that — wherever it is, whatever it pays, that's what I want to do. So I was doing a lot of indies. "The Answer Man," John Hindman wrote a really strong script. "Paper Man" [2008]. "Squid." "The Lookout" [2007]. The writing is what kept me interested in the work, because I was losing interest. Then Carnage came along and Blackbird came along [staged at Manhattan Theatre Club in 2007, with Daniels opposite "Newsroom" co-star Alison Pill]. Those were all writing choices. They were tricky. They were hard. I wasn't sure I knew how to do them. I knew I might fail. But I wanted to try. A lot of TV writing, on both cable and the networks, is getting so much better. On the cable side of things, they're taking chances. There's a creative freedom there. The writer is encouraged. He's respected in television in a way that I don't always see in movies. Certainly in theatre you see it. But not in film as much — where people rewrite and ad-lib and note things to death. And as an actor who just wants to come in and act, television is a great place for me to be right now.

Now that you're committed to doing "The Newsroom" for a second season, will you have any time for theatre? When will we see you back on stage again?

JD: Oh, sure, I'd like to think so. No idea in what or when or anything like that. But I love New York. I loved the whole Carnage thing. That will probably be something that we never top, as far as the critical and box-office reaction to it.

The chemistry between the four of you was electric.

JD: That's one reason that we all got together and did it again in L.A. We genuinely liked each other. And talk about four different people! Out of it, we've all become great friends. Gandolfini has been such a help on this HBO series, I can't tell you. The fact that he's been through it all before with "The Sopranos." He and Sam Waterston, who have both done series TV before, have been real good sounding boards for me — in terms of places I could go. Jim [Gandolfini] was just very helpful to me in getting through it. Because you feel overwhelmed at carrying the load. He knew where I was when I was struggling. He'd go, "It will get better, don't worry. But first it's going to get worse." [Laughs.] There are tricks to doing it, and Jim was a great place to go to talk about that. Christopher Wallenberg is a Brooklyn-based arts and entertainment reporter and regular contributor to the Boston Globe, Playbill and American Theatre magazine. He can be reached at [email protected].