*

Philip Seymour Hoffman is such a primal, prolific acting force on stage and screen — dotted with numerous award nominations in both mediums and capped by his "Capote" Oscar — that people frequently forget he's a fellow who dons other hats.

During the time he and John Ortiz shared the artistic reins of the LAByrinth Theatre Company (2000-2008), he directed the world premieres of five plays by Stephen Adly Guirgis (The Little Flower of East Orange, The Last Days of Judas Iscariot, Our Lady of 121st Street, Jesus Hopped the 'A' Train and In Arabia, We'd All Be Kings) and, with them, defined the troupe as a volatile, dynamic ensemble where every member came up to the mark. Long story short, he directs like he acts — full-throttle. No actor was left behind.

Consequently, it's not surprising that when he opted for a new chapeau — that of film director — he did it in the company of proven friends. "Jack Goes Boating," which sails into release in selected theatres Sept. 17 after a Toronto Film Festival launch, is something he lightly (and not inaccurately) characterizes as "an in-house project."

There he and Ortiz are, in roles they originated at The Public in 2007 — Jack and Clyde, Manhattan limo drivers locked into a dead-end life. Back, too, is LAByrinth regular Daphne Rubin-Vega in the role of Clyde's estranged wife, Lucy. New to the mix is Amy Ryan as Connie, Jack's hoped-for hook-up who is coaxed into a blind-date situation by Lucy, her co-worker at a Brooklyn funeral parlor. Both wannabe romantics are bashful "players" at this love game. Connie's idea of a suitable swain is someone who takes her rowing or rustles up a good meal. These she plucks randomly out of the air in the dead of winter, giving Jack months to hone his chick-getting skills: He takes swimming lessons from Clyde and culinary lessons from "The Cannoli," a well-endowed pastry chef who's a festering old-flame of Lucy's.

|

||

| Beth Cole, Philip Seymour Hoffman and John Ortiz in the 2007 stage production |

||

| photo by Monique Carboni |

"When I started writing this, I thought I was going to write the most vicious, mean-spirited play," confesses the playwright, who made his entrance into the play on its dark side — the crumbling marriage of Clyde and Lucy. It seems her long-ago affair with "The Cannoli" is still threatening to scuttle their marital boat, and this little "fix-up" they have arranged for their respective best-friends, Jack and Connie, is really a life preserver of sorts — their way of testing the waters to see if love is still out there.

"That part of the story was in me very strong — much closer to me as an experience — but then Jack and Connie kept popping up and not letting me go there. They were like an antidote to all of that. I think the four characters played well together. We have one couple whose relationship is deteriorating, sorta projecting whatever they can onto the couple coming together. There was the anxiety of someone whose relationship was unraveling, played against the anxiety of meeting someone new you might care about. This I saw after I had written it. I just followed the characters.

"I had an image of 'yeah, he will go boating at the end,' but, other than that, I just let the characters lead me through the play without any outline. When you do the film script, of course, you have an outline. The wonderful thing about both a play and a film is that the text is really a pretext for what evolves. It's in the translating to film that things can grow. I learned that, in film, the shooting drafts I came up with were the beginning of a couple of other drafts. Those other drafts were the collaborations, first, between the photographer and Phil and then between Phil and the editor. Each one is another draft. When I was writing my draft, Phil and I would meet and discuss things, and I could sense what he was looking for visually and cinematically — his vision, so to speak. He would include me in creating stuff that supported the director's vision — cinematic journeys that he and the photographer wanted to make with the story — and what I could do in the draft to give the scaffolding to that."

|

||

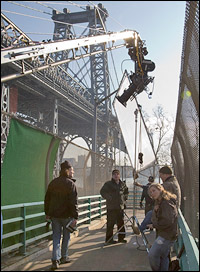

| Hoffman (center) on set with the production crew |

||

| photo by K.C. Bailey |

"Mott was somebody I had met years ago in college," Hoffman relays. "We weren't really good friends back then, but I always knew he was a D.P., and eventually we re-met on the set of 'The Savages,' and I got to work with him there as an actor, which was a much different relationship, obviously. I really liked what he did on that film, and, when my film was brought to him, he said he was very interested, so we talked and I just kinda knew right away that he was the guy. And he was the guy. I have to say it was a great working experience. He's a wonderful collaborator."

Between the two of them (three counting Glaudini — and four counting a particularly industrious location finder), "Jack Goes Boating" offers a very realistic, un-touristy view of a winter-slammed, dramatically desolate New York at a variety of locations and temperatures.

"Some scenes were set," says Glaudini, "but I suggested locations to the production manager, and he found choices for Phil and Mott to look at. We were in Long Island, Queens, Harlem and, mostly, midtown Manhattan. It was a difficult shoot. We were shooting at four in the morning in sub-zero temperatures."

Littered throughout the film is a myriad of quick scenes shot all over town, assembled by editor Brian Kates in a way that disguises the property's stage roots. "Well, thank you very much, but I'm sure not everyone will agree with you," a cautionary Glaudini begs to differ. "Once one hears that it was a play before they go in — I'm talking in terms of people who write and blog about film — once that is learned, then people look for that. But I'm a huge fan of that kind of film. I love a whole series of films that were stage plays first and then turned into films, starting with Renoir and Wyler and going on up through Lumet, Nichols and Fassbinder."

|

| Counterclockwise from right: Hoffman discusses a scene with DP Mott Hupfel, Amy Ryan and Daphne Rubin-Vega |

| photo by K.C. Bailey |

|

||

| Hoffman and Amy Ryan star in the film "Jack Goes Boating" |

||

| photo by K.C. Bailey |

His naturalistic dialogue and unadorned world-view puts him on a comparable plain with Paddy Chayefsky, the "poet of the pavements" from television's Golden Age. Indeed, one early review pegged "Jack Goes Boating" as a "Marty" for the new millennium, a comparison that sits well with Hoffman. "It is similar," he says, "but I didn't even think about that while we were shooting the movie. When I came across that review, I thought, 'Oh, yeah, that's fair. That's a fair correlation.'"

Where the movie is most reminiscent of its predecessor — a Best Picture Oscar-winner of 45 years ago — is in the awkward, painfully tentative coming-together of Jack and Connie. Hoffman and Ryan make this a very moving, very human spectacle.

"I worked with Amy before, the first time probably when I was 30," he recalls. "We were in different halves of a two one-act-plays evening. That's where we met. Then she was in 'Capote,' playing the sheriff's wife — she's pretty wonderful in that — and we've known each other, just in the circles of New York. She is really perfect in this."

As for his own performance, Hoffman brings it down a notch. "I think I did all right," he says. "It's not the best scenario, directing yourself — it really isn't — not a thing I recommend. We were trying to find another actor to play that part. I definitely didn't plan it that way — that's the truth — but we were up against the wall because you have to shoot that film in the winter. It can't be shot any other time because of the circumstances of the film. "Jack Goes Boating" is all about the fact that spring is coming. You can't shoot that in the spring or the summer. You have to shoot it in the cold winter months. That's the whole point of the movie." Woody Harrelson and Mark Ruffalo were forced out of the running by previous film commitments, so Hoffman stepped up to the plate. "Basically, we would have to put off the film for a year, or I had to do it. Putting off the film for a year is like saying, 'You're never going to do the movie,' so I said, 'Well, I'm just going to have to do it because everything else is in place. So I did, and I learned all about what that's like."

|

||

| John Ortiz and Daphne Rubin-Vega in "Jack Goes Boating" |

||

| photo by K.C. Bailey |

Given the weightiness of this double duty, he made himself comfortable as an actor by hiring two of his three stage co-stars. Beth Cole, the original Connie, did make the film cut, playing a teacher in a night school Ortiz attends. All the other roles that materialized when the play was opened up for the screen were filled by LAByrinth's rank-and-file who'd already been directed by Hoffman on stage: Richard Petrocelli, Salvatore Inzerillo ("The Cannoli"), Sidney Williams, Trevor Long, even playwright Stephen Adly Guirgis. Todd McCarthy, the actor recently turned director ("The Station Agent," "The Visitor"), flicks off a surreptitiously sleazy funeral-home boss.

"We really challenge each other and work hard on trying to evolve," Hoffman says of the company he has kept. "Everyone at LAByrinth is trying to be the best actor he can be. In the plays Stephen writes, people have a great opportunity to do that because his writing's very alive. Plays are cast because parts are written for certain actors — that's how Stephen works. He definitely writes with certain actors in mind."

So, is film-directing more difficult than stage-directing? "They both have their own difficulties," he finds. "After all's said and done, the thing about being a director of film is that it's a longer process. You're making decisions and choices and creative kinds of exploration for a longer period of time. But, in theatre, you're doing that in almost just as intense a way. It's just a shorter period of time. It's not just directing the actors. You have to work with the designers. There's a huge technical proficiency to being a theatre director. The picture you paint on a stage is something that you have to paint, just as the same thing you're going to put in the frame of a camera."

What he's proudest of in this maiden "Boating" voyage "is all the creative relationships you get to have as a film director, starting with the playwright-slash-screenwriter, working with Bob on the adaptation, then with Moff as a D.P. and going into shooting the film with them and all the actors. Then, when you finish shooting, you have a relationship with the editor. All along the way, each one of those relationships furthers the process of the film. It's a very satisfying experience."

View the trailer for "Jack Goes Boating":

(Harry Haun is Playbill magazine's staff writer. His work, including the popular Playbill On Opening Night columns, frequently appears on Playbill.com.)