*

The first king to speak in "The King's Speech" is George V (Michael Gambon), advising his tongue-tangled No. 2 Son, Bertie (Colin Firth), to make friends with the BBC microphone looming menacingly before them.

"This devilish device will change everything if you don't," prophesizes the old boy sternly — and accurately. "In the past, all a king had to do was look respectable in uniform and not fall off his horse. Now we must invade people's homes and speak, ingratiate ourselves with them. This family is reduced to those lowest, basest of all creatures. We've become . . . actors!"

At the time, the prospect of Bertie (for Albert) stuttering and struggling through a speech in public was comfortably beyond the realm of possibility since his older brother David, the dashing and articulate one, had dibs on the throne and did make that royal ascent Jan. 20, 1936, as Edward VIII — only to abdicate "for the woman I love" Dec. 10, 1936, throwing his kingship to Bertie (regally redubbed George VI).

The film that beautifully articulates the internal storm raging inside the new king is currently contending for more Academy Awards (12) than any other 2010 release; the nominations include Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, Best Director and three nods for its key performances. At the time, George VI's quiet agony was hardly noticed, lost in the shuffle, upstaged by the sort of sacrificial love-above-all story that the world loves (particularly "colonists," since the lady who snared the king was a twice-divorced American named Wallis Simpson). The two would spend the next 35 years as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, jet-setting hither and yon as society celebrities on one big glamour bender.

This fairy-tale romance is the stuff of which miniseries and made-for-TV movies are made and remade — with Faye Dunaway and Richard Chamberlain (1972's "The Woman I Love"), Cynthia Harris and Edward Fox (1978's "Edward & Mrs. Simpson"), Jane Seymour and Anthony Andrews (1988's "The Woman He Loved"), Joely Richardson and Steven Campbell Moore (2005's "Wallis & Edward") and Gillian Anderson and Tom Hollander (2010's "Any Human Heart").

Soon, their story will finally reach the big screen as "W.E." (code for Wallis Edward), starring Andrea Riseborough and James D'Arcy. The director — proving there's apparently some honor among Material Girls — is Madonna.

But what of the forgotten man in all this flurry of rose petals — the poor bloke left holding the bag called Britain? Bertie could only haltingly form sentences, yet he had to rally his country to war and make himself heard over the histrionic rants of Hitler.

"I think it's interesting to follow what history might pronounce as the minor characters offstage and see where they go," says Firth, whose sensitive portrayal of the anguished monarch keeps coming in first in 2010's Best Actor competitions.

|

||

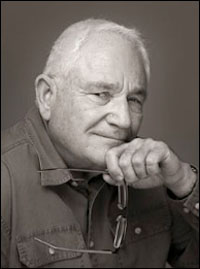

| Director Tom Hooper |

||

| photo by Laurie Sparham/ The Weinstein Company |

Consequently, while the decidedly unking-sized Bertie takes up the family coat of arms and soldiers on, Guy Pearce's Edward VIII sinks to a supporting slot, skipping off to his selfish happy-ending with this woman he loves. And sheis held to four or five lines of dialogue — one of them placing a drink order with her then-king fiancé! — but, despite that limitation, Eve Best succeeds in impressing.

"David was, I guess, the loose cannon," offers Firth. "He was charming. He was Prince Charming to a lot of people. He was very popular in this country. Bertie was in the shadows and was considered the dull one, the one without any charisma. He was misjudged because he was so debilitated by his stammer. What I think is so painful about him — and a lot of characters I've taken on who find communication difficult — is that they are people with a kind of lucidity inside. It wouldn't be a tragic case if he really was dull-witted, but, if you read his letters or his quotes or hear anything he has to say, this man had an elegance of thought and wit and language. There's no question about it. He was fiercely intelligent. He did not speak banalities. He had a sense of paradox. There's a really fine and subtle mind at work there, and for that not to be able to come out is immensely painful. His mind was on fire."

At exactly the same time George VI was desperately trying to find his voice via an unorthodox and eccentric speech therapist named Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush), in another part of London was born David Seidler, the Anglo-American who came up with the original (now Oscar-nominated) screenplay for "The King's Speech." "I even have a coronation mug made for Bertie's coronation," he says with conspicuous pride. "Also: two big flags that were printed in England and sent to the colonies to be waved at the coronation of Edward VIII — the coronation that never took place.

"I didn't find this story as much as it found me," Seidler admits. "I was a profound stutterer as a child, so Bertie was always a childhood hero of mine. During the later stages of the war when I listened to his broadcast speeches, my parents told me his stutter had vastly improved. 'If he can do that at this stage of his life, there's hope for you,' they said, so he became a symbol of hope for me. When I finally got rid of my stutter at 16, I knew I wanted to do something about Bertie. I had no idea what."

|

||

| Geoffrey Rush |

||

| photo by The Weinstein Company |

"Lionel Logue is just an occasional blip on the radar screen. The royal family does not like to talk about the royal stutter. It's swept under the carpet. But I could smell a story here so I asked a London friend to do a little detective work — which mainly consisted of looking in the telephone directory — and he located a surviving son of Logue's, Valentine. In the movie, he's the young boy who's always reading books. By the time I made contact with him, he was an elderly gentleman — an eminent surgeon retired from Harley Street and very gracious. He said, 'Yes, would you like to come to London to talk with me?' He had all the notebooks his father kept while treating the king — I thought this is the mother lode! — but there was a caveat on this letter: 'I'll lend them to you, Mr. Seidler, but you must get permission from the Queen Mother.'

"This is where my American friends realized I am really half-English and carry two passports. The British part of me said, 'You've got to do this.' So I wrote to the Queen Mum, and in due course I got a note from her, saying, 'Dear Mr. Seidler, Thank you for your letter. Please, not in my lifetime. The memory of these events are still too painful.' An American would have said, 'Dammit, Queen Mum. Who cares? I'm going to do it anyway.' But, as a Brit, when the Queen Mum says 'Wait,' you wait."

|

||

| David Seidler |

Oddly, in trying to get the property on to the boards, it was the film version that took flight first. Joan Lane, the British producer who was interested in the play, had an assistant who lived a couple of blocks from Rush in Melbourne and, during her Christmas vacation, slipped a plot synopsis in his mail chute. Seidler, having been flatly turned down by Rush's Australian agent, was mortified by this tacky tactic, but six months later that same agent sheepishly notified him that Rush was keenly interested in this little film outline unofficially slipped to him over the transom.

What interested him was the role. "Geoffrey was always the person I wanted to play Lionel Logue. From the moment I started thinking about this seriously, it was always Geoffrey Rush. At that stage, I hadn't turned the play back into a screenplay, so, since the stage play was in far better shape than the script, that's what I sent to him. He said, 'I don't want to do the play, but, if it becomes a film, count me in.' Also — and this was crucial — he said, 'You may use my name.' Which was very generous. No money changed hands, no paperwork. His name really helped get momentum going. Finally, when I did get the screenplay written — which took two and a half weeks — he read it and said, 'I'm in. I'm attached now.' Again, no money changed hands."

|

||

| Harvey Weinstein |

||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Seidler had Firth doubts, too. "I was concerned because Colin's face is the wrong shape. I don't think he looks much like George at all — but I realized nobody under 60 has the vaguest memory of what he looked like. Only stamp collectors know." In researching George VI, the actor came up against the same blank walls that Seidler did. "So much is a mystery," Firth concedes. "The flow of information out of Buckingham Palace is nonexistent. If I play a role, I want to familiarize myself with that person's world, and their profession is a big part of that. If I play an airline pilot or a doctor, I'd probably want to hang out with a doctor or a pilot for a while to see what they did and ask them questions. You don't get to hang out with kings, and they don't help consult on movies. So your resources, by necessity, are secondary."

It helped not a whit that he'd played two stammerers in the past — a World War I vet in the 1987 film, "A Month in the Country," and at the Donmar Warehouse in 1999 in Richard Greenberg's play, Three Days of Rain. "It was different every time," insists Firth. "None of that helped. It was a different guy, with different dialogue, different issues, different ways of dealing with things so we had to start again. We had to find a way to make this sound authentic and have it be painful. The audience had to experience the pain and the discomfort and the frustration, not only his but the people who are rooting for him. That had not to be compromised."

What was helpful was drawing on the screenwriter's own personal history. "Colin did a lot of research, and he did a lot of questioning of me on what it was like to stutter, how it feels to be a stutterer," Seidler recalls. "We had a lot of long conversations about it. He asked some very good and probing questions about it."

Considering the conspicuous success Firth has had with George VI, you might think he'd be first in line for the stage version, but "no, they didn't actually approach me. David Seidler winked at me a couple of times. Best let someone else get a crack at it."

The play, left by the wayside when the screenplay caught film, is now in the court of lead producer Michael Alden, who's comfortably twiddling his thumbs, reviewing his options while the movie runs its course, winning awards and audience awareness for Bertie and Lionel. Alden says he has been besieged by co-producing offers from Broadway, West End and Australia. Exactly where it will first surface will depend on cast availability, but London looks the most likely — especially since it will directed by Adrian Noble, the RSC's artistic director who brought to Broadway A Midsummer Night's Dream and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

|

||

| Helena Bonham Carter and Colin Firth |

||

| photo by The Weinstein Company |

"There is a lot of things that are in the stage play that are not in the film and a lot of things that are in the film that are not in the stage play. Yes, it is recognizably the same piece, but there's a lot of different material. Such as: In the play, Lionel Logue, Winston Churchill and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Lang, act almost as a comic Greek chorus, which works extremely well on stage — but, in a film, it would be very theatrical so that all got expunged, and some of the best lines went with it."

Also, the cast of characters has been pared down to eight — Bertie and Lionel and their wives, Elizabeth and Myrtle (played in the movie by Helena Bonham Carter and Jennifer Ehle), Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin (Anthony Andrews), Winston Churchill (a Laughton-looking Timothy Spall) and David/Edward VIII, with Wallis Simpson as a walk-on. "There are no children in it because we didn't want child actors and the expense of nannies and everything, so the princesses [Margaret and the now-reigning Elizabeth] are not in the play at all.

"The other difference is the opening. The curtain goes up, and you see a large enamel bathtub with gilded legs. Out of the water appears a head. Bertie comes out of the water, an embryo as it were, and footmen rush in and wrap him in towels, and he's dressed. There he is, with plumes and braids and all. He looks at himself in the mirror, and he says, 'I look like a Christmas tree.' That's the first line in the play."

Seidler believes the movie will be a good advance-man for the play. "I had a conversation with Richard Price, who actually put up some of the seed money for this and for Mamma Mia!. He said, when the 'Mamma Mia' movie came out, he thought it'd really kill the box office for the play, but, no — it tripled it."

At 73, Seidler — interviewed weeks before his nomination was announced — figured, if nominated, he would be the oldest screenwriter ever in Oscar contention, but no again: "I think I'd now be the second oldest. The oldest is my idol, George Bernard Shaw, who, in 1939, at 83, was nominated and won for 'Pygmalion.'" When notified of the win, GBS proclaimed, "This award's an insult!"

Seidler laughs at this and promises, should he win, "I certainly won't say that!"

View the trailer: