They were limited runs, you say? Correct. They all featured prominent stars? Right, again — Julianne Moore made her Broadway debut in David Hare's The Vertical Hour; Broadway perennial Nathan Lane anchored the revival of Simon Gray's Butley; and Hollywood queen Julia Roberts headlined Richard Greenberg's Three Days of Rain.

And the third thing? Just a small matter: they all made money.

Though each production was on the boards for only a few months, leaving producers only a narrow window of opportunity in which to earn back their investment, every one of these shows passed the finish line in the black.

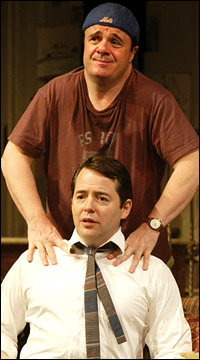

Other examples of profitable limited-run plays in recent seasons include Frost/Nixon with Frank Langella; The Odd Couple with Lane and Matthew Broderick; The Faith Healer with Ralph Fiennes; Glengarry Glen Ross with Alan Alda and Liev Schreiber; Julius Caesar with Denzel Washington; Raisin in the Sun with Sean Combs; and Long Day's Journey Into Night with Vanessa Redgrave and Brian Dennehy.

These days, there seems to be only two ways to make money on a straight play on Broadway. One is to ride across-the-board raves and a clutch of awards (including the Tony and the Pulitzer) to a long, healthy run, as Proof and Doubt did. The other is to secure the services of a name star and nail him or her down for a run of anywhere from 10 to 20 weeks. Open runs of plays that lack rave reviews or multiple trophies rarely show a profit. It's the Stars

On the surface, the reasoning can seem counterintuitive — open runs don't work as business models, but purposefully short runs do? But, according to many Broadway producers, in this day of public fascination with celebrities, it all comes down to the name about the title.

"It's the stars," replied Emanuel Azenberg, one of the producers of The Odd Couple, when asked what was the main thing driving the limited-run trend. "The stars sell out the show. But they don't want to play for a long time."

"Stars play a major factor in it," said Jeffrey Richards, who won a Tony Award for Best Play Revival for Glengarry Glen Ross, and will this season produce limited runs of Tracy Letts' August: Osage County and Harold Pinter's The Homecoming. "Years ago stars like Julie Harris would sign up for a year. That diminished over the years. Nowadays because the options are so varied in other worlds of entertainment — television and film — many agents won't let their stars take six months of their time for one engagement."

Stewart Lane, a producer of the coming Kevin Kline-Jennifer Garner revival of Cyrano de Bergerac, which will play a mere 10 weeks at the Richard Rodgers Theatre, cited David Hare's Skylight as one of the first examples of the current limited-run model. The 1996 production ran for only four months, primarily because star Michael Gambon was free for only that short period of time, and didn't want to perform any longer than that. The production recouped its investment in less than six weeks.

|

||

| Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick in The Odd Couple. |

||

| photo by Carol Rosegg |

"Because the stars are not playing forever, they can't ask for the moon," said Azenberg. Richards echoed that sentiment. "There is realization that by giving less time to a production [the stars] are more understanding of the need of the theatrical production to recoup its investment, and they frequently will be cooperative to enable a show to go into the black." To make it more worth an actor's while, they are often offered, in addition to a low-end salary, a percentage of the play's profits.

Stewart Lane declined to confirm an account in the New York Post that Kline had accepted a salary of only $2,000 a week, with no percentage of the show's profits, in order to secure the brief 10-week life of the production.

Another Incentive

Lane, however, argued that another factor often goes into a name performer's decision to sign on for a Broadway show: sheer desire to do the project. "Kevin really wanted to do this role," said the producer. "A solider who wants to fight for his country does it until he dies, passionately. A mercenary does it just because he's hired. Kevin wanted to do this."

Julia Roberts, a movie box office powerhouse for more than a decade, has little to gain by acting in a play. But her longing to do a Broadway show was well publicized through news articles and interviews. Similarly, it was widely perceived that Sean Combs intended to use Raisin as a way to prove his acting chops to the entertainment industry.

Some limited-run plays break from the prevailing mold in that they don't feature a major star. Such a case is Letts' August: Osage County, which played to great reviews when it debuted at Chicago's Steppenwolf Theatre Company earlier this year. Producer Richards, however, argued that the engagement actually has not one, but two stars.

"You're introducing Tracy Letts, who has certainly developed a reputation Off-Broadway with Bug and Killer Joe, to Broadway audiences. And the other star of this production is Steppenwolf Theatre Company. If we were importing this play from England, it would be the equivalent of importing the National Theatre. Steppenwolf is one of our most valuable contributors to the theatre scene nationally."

In the world of limited runs, schedules of the star and the production are entwined. When the first is available, the second goes into motion; when the first departs, the second shuts down. But, one might ask, need this be the case? If a play is proving a big hit with one star, might it not be sustained by casting another equally big star to take over? Well, no. Azenberg quickly explained why that proposition does not typically work. "Part of the excitement for the star is originating the work," said the producer. "Assuming the reviews are good and you want a replacement, the prospect of recreating an actor's work is not attractive to another actor." And so, when Roberts, Moore, Washington, Lane and Fiennes left their shows, their shows left with them.

Azenberg did not think that the mere fact that a play was a limited run — as in "Run, don't walk, buy your tickets now!" — added any heat to a project. Neither did Richards, who only allowed that the finite calendar was helpful in marketing to the extent that it gave the audience "a certain idea when a certain play will be available to them."

Lane, however, was a little more sanguine about the Barnumesque qualities inherent in the limited run. "Well, that's good theatre," he said of the strategy, laughing. "'Time is running out!'"