*

The so-called lost boys in "Wendy and the Lost Boys" by Julie Salamon [Penguin] are principally Andre Bishop, Christopher Durang, William Ivey Long and Gerald Gutierrez; young in spirit and ageless, perhaps, but not exactly "lost." The one who was lost, if you will — and who some analyst somewhere might even theorize was a "lost boy" — was Wendy Wasserstein herself. The Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, who died at the age in 2006 at the age of 55, was highly accomplished and by all reports quite a character. Salamon draws a picture of a bubbly, wise, anything-for-a-friend person who seems to have been overwhelmed and very much weighted down by severe and self-defeated unhappiness. And when I say "weighted down," I don't chose those words lightly.

Wasserstein was born in 1950 in Brooklyn, into a family of ambitious, upwardly mobile and successful Jews — I think that's probably the most accurate description I can come up with — who believed there was nothing they couldn't accomplish. As long, that is, as they barricaded unflattering truths behind doors locked so tight that said truths vanished. Vanished, yes, but with a tendency to rematerialize like Ibsenesque ghosts. Here is Wendy in a jacuzzi at an exclusive spa at 24, sharing the waters naked with Clark Gable's widow (who has nothing to do with anything), learning that her idolized big sister was fathered by an uncle. Here is Wendy at a book-signing in Rochester at 48, confronted by a 60-year-old in a wheelchair who demands to know why the Wassersteins kept him locked away in an institution since he developed encephalitis or meningitis or something — the actual cause is unclear — when he was five. Wendy, meet your other brother.

| |

|

|

| Wendy Wasserstein |

Lucy Jane Wasserstein — father unknown, possibly one of the boys (but Wendy refused to tell even them) — survived and has apparently thrived. Not so the mother, who in her article only hinted at the true complications of her pregnancy. She never physically recovered, and spent her final six years struggling with a variety of conditions before succumbing to lymphoma. All the while keeping the severity of her condition a secret to even her closest friends, the sort of matter that true Wassersteins never discussed. Even with each other. As Lucy Jane entered kindergarten at the Brearley School — a school to which young Wendy, decades earlier, had been too ungainly or too uncouth or too Jewish to gain admittance — Wasserstein went into a final decline. She died on Jan. 30, 2006, shocking friends, family and admirers alike.

| |

|

|

| Wendy, already showing signs of illness, bringing Lucy Jane home from the hospital. | ||

| Courtesy of the Wasserstein family |

An uncommon woman, to borrow the title from the play which first established Wasserstein as a playwright to reckon with. With uncommon talent, yes, and an overwhelming set of personal problems that seems to have kept her under a perpetual cloud. Salamon, in "Wendy and the Lost Boys," illustrates the career and life of Wendy Wasserstein in smashingly good, can't-put-the-book-down read-through-the night form.

| |

|

|

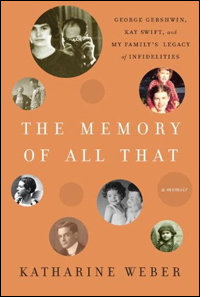

| Cover art for "The Memory of All That" |

But who wants to spend the first half of the book — literally, the full first half — reading not about Kay and George but about one Sidney Kaufman, who've we've never heard of and never had reason to. Kaufman was a serial underachiever, all bluster with little accomplishment, a minor cog in the world of motion pictures. (According to his daughter, he more or less developed the use of completion bonds for independent films, which is sort of an insurance policy for motion pictures.)

Kaufman was a spectacularly poor provider, insolvent, unreliable and worse. At one point, Weber reports, her father left their Forest Hills (NY) house and disappeared for 18 months. Kaufman was a good talker with outsized charm, and a serial adulterer; Weber tells us, in one fascinating stretch, that one of his mistresses had affairs with Carl Sandburg and Thomas Wolfe, another with Maxim Gorky and H.G. Wells. (Weber accumulated bits of the story over the years, with many perplexing shadows filled in courtesy of her father's FBI file, some 800 pages-worth.) So yes, Sidney Kaufman makes interesting reading. From the moment of his birth, in fact: Kaufman's mother left her job in a sweatshop to give birth, not long before the place — the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory — burst into flame in Manhattan's deadliest workplace tragedy of the 20th century.

But "The Memory of All That," title borrowed from an Ira Gershwin lyric, is supposed to be about grandma Kay, who only comes along in the second half. It turns out, though, that Ms. Weber knows what she is at; her memoir consists of numerous nonmatching strings, which she somehow manages to masterfully pull together. Kay had been married to James Warburg, scion of the ultra-wealthy banking family, for eight years when she met and fell in love with George. Two of Kay's children seem to have rejected their mother for destroying their family; the middle daughter, Andrea, appears to have just as irretrievably fallen under George's spell. (For a short period of his brief life, Gershwin avidly took up photography. One of his most striking compositions, a self-portrait from 1934, is centered on 12-year-old Andrea; George sits behind her — or maybe she is on his lap — taking the photo in a mirror, the Leica obscuring his face.)

| |

|

|

| Kay Swift | ||

Weber spends less time discussing her mother and more on her grandmother, who started the next stage of life after Gershwin by marrying a rodeo cowboy, writing a book about it, making a film about it (starring Irene Dunne as Kay), and divorcing said cowboy. And there's plenty more to be said about the fascinating Kay. Swift spent a good part of her 95 years as the unofficial artistic guardian of George's music; having sat beside him on the piano bench for half his adult life — and being an accomplished musician herself — Kay was the person to go to for songs, for information, and for demonstrations of how George intended his music to sound. Swift was also our prime expert on the score for Porgy and Bess, having been deeply involved in its creation. Would that she was around just now.

(On a personal note, let me add that I consulted Kay several times on matters Gershwin. The last time I saw her was especially memorable. The 93-year-old Swift turned up at a show I produced in 1990, offhandedly introducing me to her 84-year-old friend Frankie. Who turned out to be Frances Gershwin Godowsky, kid sister to George. They both especially loved the score and the show, Bill Finn's Falsettoland.)

All said, "The Memory of All That" does indeed tell us about George and Kay, offering new insights that will be of interest to Gershwin followers. Weber also tells us about her father; his numerous associates, some of whom were decidedly shady; her grandfather James Warburg, a central cog in the bogus "International Jewish banking conspiracy" that still circulates in some circles; and numerous passersby. There's even a glamorously beautiful Englishwoman with one arm, along with plenty of memories that might raise an eyebrow. Like the night Zero Mostel came to dinner, circa 1962. The then seven-year-old author watched as he "reached into the basket of dinner rolls on the table and licked each one before putting it back, while everyone laughed uproariously." Did that sort of thing ever happen at your house?

| |

|

|

| Cover art for "Fine and Dandy: The Kay Swift Songbook" |

Kay Swift's Greatest Hits, as it turns out, number three; nothing included in the songbook is likely to increase that total. The most famous of them — or I should say the most familiar — is "Fine and Dandy," from the show of the same title. The other two are fine ballads, the lovely "Can't We Be Friends?" (from The Little Show) and the even better "Can This Be Love?" (from Fine and Dandy).

I must note, however, that "The Kay Swift Songbook" has seen fit to change the keys for the two ballads (along with several other songs). This sort of thing rarely bothers me, as the published sheet music versions back in the old days were typically altered from the composer's manuscript anyhow. In the case of these two songs, though, I find the newly published versions — which seem to be straight transpositions — more difficult to play. I long ago memorized "Can This Be Love?" in the key of F, and still enjoy sitting at the piano with it. In D, my fingers just don't seem to want to find the notes. Odd, certainly; but if I'd first located this incredibly beautiful song in the new arrangement, I don't know that I would have bothered to keep it on the piano rack.

(Steven Suskin is author of the recently released updated and expanded Fourth Edition of "Show Tunes" as well as "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," "Second Act Trouble" and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He also pens Playbill.com's On the Record and DVD Shelf columns. He can be reached at [email protected].)

* Passionate about theatre books? See what the Playbill Store has on its shelves.