*

You gotta have heart, it has always seemed to me, although in my case I spell it Hart. As in Lorenz Hart, also known as Larry Hart. The lyricist, who wrote so many of our very favorite songs, died in 1943. While his words remain familiar — at least to those who care about the American popular song of the Roaring Twenties and the depressed Thirties — his life has always been something of a closed book. The pages are opened for us, somewhat, in A Ship without a Sail: The Life of Lorenz Hart by Gary Marmorstein [Simon & Schuster].

The life of Hart is not unknown, altogether; the oft-told basics tell of a talented-but-tortured misfit with a dwarf-like body and the inability to see himself as an object worthy of love. At least, that's what they tell us. For many years, we heard little of Hart; his legacy was seemingly controlled and somewhat hidden by his long-time collaborator Richard Rodgers. Rodgers, as we've learned, was a difficult man. He seems to have been conflicted about Hart, and about his long partnership with Hart, and even about their joint song catalogue; during the Rodgers & Hammerstein years, the composer seemed to try to brush away references to his first collaborator and compliments about their songs. The pair met and began working together when Dick was 16 and Larry was 23; seven years isn't such an enormous gap, but it is when you are still in high school. As Rodgers wrote of their first meeting, "I left Hart's house having acquired in one afternoon a career, a partner, a best friend, and a permanent source of irritation."

By 1940 that irritation was indeed permanent, by 1941 it was intolerable and by 1942 the partnership ceased. Following the lyricist's death the next year, Rodgers seemingly washed his hands of Hart. We are not here to psychoanalyze Mr. Rodgers, a pastime which other writers have engaged in with relish (accurately or not). He does, though, seem to have retained a fair share of guilt and hypersensitivity. Being the king of Broadway, more or less — besides writing all those shows, Rodgers was one of the most active and successful producers of his time — he seems to have purposely kept chatter about Hart to a minimum.

The moratorium was broken, with a vengeance, in 1976. Rodgers' 1975 autobiography "Musical Stages" had discussed life with Larry at length, albeit in a gentle manner. This was followed, the next year, by not one but two biographies. "Rodgers & Hart: Bewitched, Bothered and Bedeviled" came from Samuel Marx (a Hollywood writer) and Jan Clayton (the original Julie in Rodgers & Hammerstein's Carousel). I have not had time to go back and read this — or the other old books — referred to here, but I remember the Marx & Clayton book being chatty and something of an eye opener. For the first time we got a sense of how tortured, or "bedeviled," Hart was; we also got a clearer portrait of Rodgers. While he had a well-earned reputation in the business, this might have been the first time the reading public learned that his personality wasn't quite so sweet as his music. Also in 1976 came "Thou Swell, Thou Witty," from Hart's sister-in-law Dorothy. This gave us an inside view of Larry, yes; but her portrait of a "swell" guy didn't jibe with the "bedeviled" Hart of Marx & Clayton. Let alone the fellow Rodgers called "my favorite blight and partner." Mrs. Hart and her husband — actor Teddy Hart (who created the role of Dromio of Ephesus in The Boys from Syracuse) — felt that Rodgers had more or less engineered a hijacking of Larry's will; they waged a legal battle with Rodgers, which ended poorly for the Hart family. So Dorothy might have had a bias in "Thou Swell" and her subsequent writings. (The contested will takes up the first dozen pages of Marmorstein's book, and is strongly in the anti-Rodgers camp.)

Passionate about theatre books? See what the Playbill Store has on its shelves.

|

||

| Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart |

Oddly enough, we do get a clearer picture of the real Rodgers than elsewhere. While Rodgers covered the Hart years — through a gentle filter — in "Musical Stages," Marmorstein makes good use of the trove of candid, complaint-laced letters the composer wrote through the Hart years to his wife Dorothy. So we do get an enhanced understanding of the relationship from the beginning (when Rodgers looked up to the so-much-older Hart) to the end (when Rodgers felt like he was saddled with an unruly, drunken child). So here is a new picture of Richard Rodgers; but Larry Hart, in this latest biography, remains but a sketchy, troubled soul.

On a personal note, let me add that I have in the recent past stumbled over odd but concrete evidence of the long-gone Hart. Marmorstein discusses the under-employed lyricist spending summers at a boy's camp up in the Adirondacks — where, on the first night, they would read Balzac and O. Henry. This is the same place my son attends, although Balzac is no longer on the agenda. (As soon as I finish writing this review, it is off to Visiting Day. Larry got there by taking the night boat to Albany, then catching a train inland to Riverside — which doesn't seem to be there anymore — and then being shuttled in a car. Me, I'll just get on the N.Y. Thruway and drive for six hours.)

Closer to home, one of those old class photos on the wall at my kid's school is of the Dramatic Club, 1913. Sitting there on the end in black tie is the 17-year-old Hart, sporting a headful of hair but instantly recognizable. And reading Marmorstein's description of the penthouse duplex that Hart bought in 1939 — at the Ardsley, a block away from school — I realized that this must be the apartment that a school friend of my daughter lived in. I had noted the extremely odd layout, with the living areas widely separated; Marmorstein tells us how Hart found it suitable, because he lived with his mother and could keep her relatively out of sight.

Passionate about theatre books? See what the Playbill Store has on its shelves.

|

||

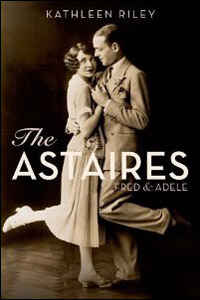

| Cover art for "The Astaires: Fred & Adele" |

But Adele retired in 1932, decamped to England and married a Lord. (Who immediately proceeded to drink himself into a stupor, followed by an early death. After which she married a second alcoholic — an American one — who did the same.) Fred, as you might have heard, went to Hollywood and tried the talkies; he soon linked with Ginger Rogers, who remains his most-remembered dance partner. Adele never seems to have been filmed, which means that her legendary magic is remembered only by people who were attending theatre prior to March 1932.

Now, thanks to Ms. Riley, we have a full-scale portrait of Adele and her brother Fred. And it is a lively tale, as the Austerlitz kids from Omaha storm New York with their stage mother and fight their way from the lowest rungs of vaudeville to stardom. Not unlike Gypsy, but with class and talent. And in which the young hopefuls they befriend along the way bear the names Gershwin and Coward.

The Astaires scaled the heights in New York but cemented their fame in the London transfers of three Broadway musicals — For Goodness Sake (known overseas as Stop Flirting), Lady, Be Good and Funny Face — so it is very much an international affair. Riley guides us through this exceedingly well, recreating the theatre world in the days between the War and the Crash. In contrast to the book reviewed above, we get a true sense of Fred and Adele. And not just with descriptions of their talent. Their characters, their voices are present on these pages. Riley had access to what seem to be voluminous archives; she also seems to have had the cooperation of Ava Astaire, who had close relationships with her father (who died in 1987) and her Aunt Delly (who died in 1981).

|

||

| Adele Astaire |

The Astaires, as the English-speaking world's favorite dance team of the 1920s, are said to have glided effortlessly and gracefully across the stage. Which, quite neatly, serves to describe Ms. Riley's book.

(Steven Suskin is author of the recently released updated and expanded Fourth Edition of "Show Tunes" as well as "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," now available in paperback, "Second Act Trouble" and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He also pens Playbill.com's On the Record and DVD Shelf columns. He can be reached at [email protected].)

*

Passionate about theatre books? See what the Playbill Store has on its shelves.