*

Australian baritone Anthony Warlow, an opera and musical theatre star Down Under, has played his share of roles in which the leading man doesn't overtly "get the girl." That is, the relationships were platonic. Uncle Archie in The Secret Garden. Higgins in My Fair Lady. The title role in Man of La Mancha. And so it goes with Oliver "Daddy" Warbucks, the billionaire Republican of the Tony Award-winning 1977 musical Annie. His leading lady is an 11-year-old orphan, first seen in the funny papers in a comic strip created by Harold Gray.

Warlow has played role twice before, in Australia. The show's lyricist (and original director) Martin Charnin was so impressed that he pushed for Warlow's hiring for the new 35th-anniversary Broadway revival being directed by James Lapine. We chatted with Warlow in his dressing room at the Palace Theatre during previews.

Annie is one of those shows that is for both adults and kids — there's a level of craft, sincerity, risk and relationships in the writing that makes it all more than just bubble gum.

Anthony Warlow: I think what James [Lapine] has done is make it a kids' show, but an adults' show, as well. That's why I was interested in it because I knew that James would put his signature on it. As hard as it may have been in the process and as challenging as it has been, I think that it's paying off. Particularly, for the Warbucks character, you really do feel that there is a connection from the first scene and the arc through to the end. When I've done it in previous productions — these last two, for instance — the strokes have been very broad and quite comic. In the other productions, the first act is comic, and then the second act becomes a drama, and you've got to find somewhere — particularly with "NYC," where literally you have four minutes — to change from this man who didn't want the kid in the room to wanting to adopt her. There's got to be some kind of emergence of her spirit getting into his armor. That's my challenge for this thing, and to keep it truthful.

| |

|

|

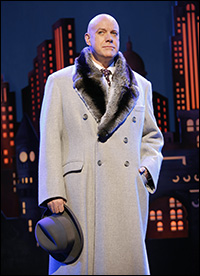

| Anthony Warlow in Broadway's Annie. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

AW: Yeah. I mean, there's a wonderful moment that is very, very different — very different — to the scene work in the original. We've made changes, as you may have noticed. Annie comes in and he says, "Annie, can we have a man-to-man talk? I was born in a very poor family," and talks about that and gives her the locket. And then she doesn't want it. So he's giving his life over to her — he's opened up — and then she says no. So the stakes have gone: "Bang! Crash!" Of course, he says, "I'll tell you what, I'll find them for you. Don't get upset." In the earlier incarnation, it was "Oh! Don't, don't, don't… Don't be upset! Don't! Kids! I don't know how to deal with this. I'll get you a brandy!" Funny, funny, funny. In this version, as James rightly said — and it is very true — this guy is used to getting everything he wants. He's a winner. [Warbucks] is saying to her, "You've got no life. I'm offering you a life. And, I like you, and we can get on." And, she says, "No. I don't want it. I want my real parents." This is a guy who's never been said "no" to.

AW: That's right. First slap in the face. So I play that in this version. When she puts the locket down, it's real.

A moment of subdued anger and frustration for Warbucks.

AW: "How?" "You little…!" You noticed I probably do a little bit of that. James [is] kind of deconstructing the show and then reconstructing from places of truth. So even the Hannigan comes from an absolute place of truth. It's not all shtick. And, for me particularly, he's pulling back a lot of the possibilities of broad, sort of cantankerous, clustering, kind of billionaire acting, and that's wonderful for me because I've experienced that side. Now I've come back, into this production, and [James] said to me — in Brisbane, actually, when we spoke when I was offered the role — "Even though you've been doing this role for nine months, what have you, are you prepared to strip off all that you've done and start from scratch?" And, I said, "Yes. That's the challenge. That's what I want to do." And, with his guidance and the guidance of Deborah Hecht, of course, who is the incredible dialogue coach, I think I'm in very good hands. In a lot of productions, I've been told that Warbucks, dialect-wise, has been Upper East Side, but here we're working on a very grounded New York accent, and that informs many, many parts of the plot very, very well.

| |

|

|

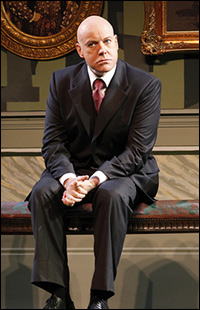

| Lilla Crawford and Warlow in Annie. | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

AW: In the early days of rehearsal, we — particularly Grace and Warbucks — were told not to touch. We don't want to touch this kid. That was really hard to play because my instincts were to touch the kid — even just to say, "Come on, now, away from here." There's that telling moment when she goes to the beggar [in "NYC"], and he grabs her to say, "No, no, no, no, no… That's a smelly, bad person." And she doesn't care. She says, "Give him some money." That's one of the first little chinks in the armor.

She falls asleep at the end of "NYC" and Warbucks cradles her and carries her off.

AW: What I've played with is that picking her up is [like] carrying this thing, and she flops, and then [I'm thinking], "What do I do with this? Oh, what the hell am I doing here?" That's a sweet moment.

You love finding these moments and shaping them.

AW: That's why I'm here. The challenge for me is to find a real flesh-and-blood spirit that embodies a character that, with all due respect — and I've spoken to [librettist] Thomas Meehan about this — was somewhat scantily written.

I've never heard "Something Was Missing" sung so beautifully. You give it much more of a tenor take that reveals a very sweet core to this tough man. Sound becomes character.

AW: Absolutely! I'm so pleased you picked up on that. I always come from a point of lyric. That's the way I sing my stuff, and I wanted that to be the epiphany moment for him — what you see is the heart of the man. That's the moment. I chose to put in two falsetto moments, not because singing the F is hard — it's not — but I wanted to actually remember that I'm talking to this little girl, and I don't want to actually overpower her with Warbucks; I want to overpower her with Warbucks' heart, and that's the reason for [those notes]. Of course, the hero does come out in the end — [with] the big Broadway, give-'em-the-money-notes that are at the end of the song. It's a challenge to sing. It's not presentational at all. James said, "Sing everything to her. It's about her." I said, "Well, I know it's a duet." It really is a duet, and that makes it even more poignant.

| |

|

|

| Warlow in the Sydney revival of Annie earlier this year. | ||

| Photo by Jeff Busby |

AW: Yeah, he made his money in the war.

He's an "industrialist" in the show, but possibly a munitions manufacturer, no? He made his fortune making bombs and tanks in the Great War. Was that in the comic strip?

AW: Yes. That's his life. He started off as a telegraph boy and worked for a scrap iron merchant, took over the business, and then when World War I happened, he got lucky and sold the scrap metal to be melted down and made into planes, trains and automobiles, for the war. That's where the name "Warbucks" comes from.

Is this all in Gray's comic strip?

AW: This is partly in his comic strip. It's partly in the other books that I've found and read, which have been written, and after conversations with the creative team. I found that very interesting. He hated Roosevelt — loathed Roosevelt.

Gray or Warbucks?

AW: Gray and Warbucks. And there's a moment where Gray kills [Warbucks] off [in the comic strip], I think in '44. Gray thought that the political time saw that capitalism was not acceptable to be talked about. So he killed him off. But then he comes back at some point. He's reincarnated. When Roosevelt died, there is a comic — one of the strips — where Warbucks is seen dancing on [Roosevelt's] grave.

In the comic strips, Warbucks used to go off onto these mysterious missions and things, and Annie would be left to fend for herself, and then he'd just appear six months later. He'd be off doing stuff with Stalin and goodness knows what, so there's quite a dark side of him. Lyricist and original Broadway director Martin Charnin directed you in Annie in Australia in 2000. Was he your advocate for getting the Broadway production?

AW: He was. He really was. I think it's hard for anyone to give up a child like this, but I think he's been very gracious with it and allowed James to do his version of it. I know that there have been notes going back and forth from all sections of the team, and James has, in part, said, "I agree with this. That's fine. I'm putting my foot down here because it's not my vision." And, they said, "Okay, well if that's the case, then we'll rewrite this little bit here." And, it's been a compromise, but I think a happy one.

Have musical theatre and opera always been part of your world?

AW: Yeah, they have. I started off classically. I started off being trained as a boy soprano and then singing classically — and wanted to be that histrionic baritone on the operatic stage. Got to do it! I've never really heard my voice as being beautiful. I've heard it as a good tool to be able to omit emotions and to tell the story, and that's how I work. My icons — my idols — were people like Tito Gobbi, who had a big sound, but wasn't afraid to gravel it up or scream a note to create an effect. That's the way I work. I studied lieder. I've studied, which is why I have a good breath capacity. What I don't want, and I've tried not to do, is to make it look difficult. I want my music and my singing to be so easy that people think, "Oh, I can do that," and when they try, they can't. I love modern art, and I collect antiques and modern art, and there's that tension in using different colors. And, that's kind of what I am — a vocal colorist.

| |

|

|

| Warlow and Ana Marina in The Phantom of the Opera in Melbourne, 2007. |

AW: No, I never thought about the Met. I love watching things in the Met. It's a bit too big a house for me.

You never thought Broadway would happen?

AW: Never thought it would.

Geographically, too far from your life in Australia?

AW: Yeah, but I always thought my best bet would be the West End because being Australian, and part of the British [heritage], and a lot of Aussies did go and do go. I did The Phantom at Albert Hall. That's all, and that was a spit and a cough at the end, which is lovely to be part and to be asked to do it.

What part of town are you living in?

AW: 42nd Street.

Oh, you're right here!

AW: Yeah. It's fantastic! What's your relationship been with New York so far? Have you been going to art museums?

AW: Yeah, I have. I'm a member of MoMA now, and I'm a member of the Met[ropolitan Museum of Art]. Every opportunity I can, I go to those museums — the Guggenheim! — and I just wander. When I have time off, and I know I don't have to sing that night, I just sit and have my lunch there, and I look at that incredible art that I see in books at home. We get art in Australia. We get touring exhibitions and what have you, but to see this plethora of incredible talent in buildings that are simply streets apart. It's wonderful.

| |

|

|

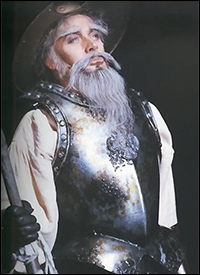

| Warlow in the 2002 Australian production of Man of La Mancha. |

AW: That's where I developed my discipline. My father was a photographer — a portrait photographer — a beautiful, beautiful photographer. My mother had a most glorious mezzo voice — not professional, just trained by the nuns — and I think that's where I have my range, because I'm basically a high mezzo in that world.

You're a bari-tenor.

AW: I'm a bari-tenor, yeah. And, I can change the sound depending on the role that I'm doing. I weight the voice for Annie and bring it out in the more tenorial stuff.

What was the music in your house when you were growing up in the '70s? Helen Reddy?

AW: No, actually! We had a piano, and my mother would sing, and we'd have lots of sing-alongs on Sunday nights. It was everything from Ivor Novello through to Noel Coward. The first recording my father bought me — I was 11 — and he bought me Harry Secombe singing. Harry Secombe had a beautiful tenor voice, and I think he did Pickwick on the West End many, many years ago. There's a beautiful song on it — "If I Ruled the World." It was an album of his songs, and I adored this sound, and I wanted to be that. It was the following year that [my father] said, "Would you like to learn to sing at the conservatorium?" So he enrolled me at 11-and-a-half. That was the beginning of studying music.

(Kenneth Jones is managing editor of Playbill.com. His first brush with Annie was seeing a performance of the first national tour the day after Christmas in 1978 at Detroit's Fisher Theatre. Follow him on Twitter @PlaybillKenneth.)

Watch highlights from the new Broadway production of Annie.