It's official. The new director of Britain's Royal National Theatre is Rufus Norris. This is a popular choice, especially among actors who love him, but a slightly unexpected one. Despite his coming up fast as favorite over the past few weeks, he's an outsider, not of the mould of the five previous directors — all of whom are from the same hothouse educational institution of Cambridge University. This one is different. Born in Africa, brought up in Malaysia, and educated in a state school in Birmingham, he doesn't fit the perfectly groomed cookie-cutter cookies that we've seen before. His first college was the Kidderminster College of Further Education before he went to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art to study acting. While he was trying to be an actor, he played for four years in an indie rock band and paid his rent by working as a housepainter. He wasn't, he said, very good at it.

When the announcement was made to the staff, in the National's Lyttelton Theatre, a cheer went up that could be heard all over the concrete palace that constitutes our symbol of great drama on the South Bank of the Thames. It was louder, chuckled the outgoing director, Nicholas Hytner, than anything heard in this building since Alfie first fell down the stairs in One Man, Two Guvnors.

Rufus is likeable, no question about that. He has warmth and charm and a way of persuading, rather than insisting, which makes him popular, indeed loved, by the actors he works with. He's extremely good-looking in a dark-and-handsome way, and married to the playwright Tanya Ronder with two teenage sons.

And he's done some really fine work as a play director, not only at the National, where he's been an associate director for the past two years, but also at the Young Vic and in the West End. But there were other, better-known and arguably more distinguished names in the frame for the top job, among them actor/director Kenneth Branagh; Ed Hall, son of the National's second Director, Sir Peter Hall, and himself head of Hampstead Theatre and of Propeller, the all-male Shakespeare company; Phyllida Lloyd, whose all-female production of Julius Caesar is currently playing in New York; and Stephen Daldrey who, having run the Royal Court before setting out as a freelance director of genius with productions as different as An Inspector Calls and Billy Elliot behind him, would have seemed the obvious candidate.

| |

|

|

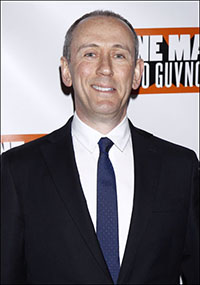

| Nicholas Hytner | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

The National, which has always been ugly and difficult to negotiate, is still both of those, but it's now user-friendly and one of the best places in London to hang out. That, almost as much as the nobable plays his leadership has brought to our attention, is Nicholas Hytner's legacy.

| |

|

|

| Nick Hendrix in The Light Princess. | ||

| Photo by Brinkhoff/Mögenburg |

The wonder that I can appreciate is the joy of seeing an extremely difficult piece of theatre almost perfectly executed. The Light Princess is, to me, a silly story of a prince from a seafaring country who is so shocked by his mother's death that he can no longer smile (sounds like a good reason to me) until he meets a princess from a neighbouring desert country who is so shocked by her mother's death that she loses gravity and floats above the ground until they meet and he learns to smile and she learns... to swim.

At least, I think that's what happens. I lost interest in the plot shortly after The Light Princess started, but I was rivetted by the stagecraft that makes the production happen. The princess is borne aloft by an assortment of wires and sturdy black-clad 'invisible' men who lift her and move her into the impossible upside-down positions that her lack of gravity imposes on her. This is so brilliantly planned that after a while you really do think she's floating. This must be down to the aerial effects designer, Paul Rubin, but the imagination and practical ideas of the director, Marianne Elliott (co-director of War Horse) and her large team of designers cannot be overestimated. The actors sing beautifully, even when doing idiotic things on parapets and in simulated lakes, and all the performances, especially that of Rosalie Craig as the eponymous princess of the title, are as superb as we expect from the National.

The physical execution of this fairy story is so extraordinary that even I, who don't care for Tori Amos' music and hate fairy tales one and all, will go back again and again to see The Light Princess. It is productions such as this one which justify the existence of the Royal National Theatre, to give it its proper title, as work on this scale cannot be accomplished in the commercial sector. No Broadway musicals producer, even the most foolhardy, would ever conceive of a show on this scale. Despite the lavishness of Big Fish and Kinky Boots, imagination on this level would be unimaginable on the other side of the Atlantic. Or even on this side, in the absence of a National Theatre.

(Ruth Leon is a London and New York City arts writer and critic whose work has been seen in Playbill magazine and other publications.) Check out Playbill.com's London listings. Seek out more of Playbill.com's international coverage, including London correspondent Mark Shenton's daily news reporting from the U.K.