*

Kelly and Moose Murders, which ran a total of two performances (collectively), and Breakfast at Tiffany's, which closed in previews at minus-2, were infinitely more infamous — but poor Carrie is the one forever cursed as the bedrock of bad Broadway shows, no small thanks to theatre historian Ken Mandelbaum, who called his chronicle on 40 years of flops "Not Since Carrie."

One thing that has happened since Carrie might just warrant a re-titling: namely, her comeback — easily the greatest since Nixon and, before that, Lazarus. Officially, this came to pass at Off-Broadway's Lucille Lortel Theatre on March 1 — in like a lion, as they say, and mostly because of its own legendary, marinated awfulness.

Even its lyricist, Dean Pitchford, admits that much. "As hurtful as it was when that happened — and kinda shocking, too, because there were lives and stories, a lot that was not understood or explained in the easy summing-up of that title — we would not be here today if it was not somehow enshrined," he readily concedes. "If it had just sorta slunk off and joined the ash heap of Broadway shows that had closed, people would probably not be as vigorously defending it and vigorously pursuing it."

Yes, after three years in the remaking and a full month of intensive, all-hands-on surgery in previews, Stephen King's telekinetic teen killer pounces anew, as vivid (and patched-up) as The Creature in Dr. Frankenstein's laboratory — alive! Still, there's something different about her — like, say, the times: in the light of current events, Carrie White looms like a pioneer crusader against high-school bullying. So what if her strike-back has enough zeal and overkill to wipe out a whole student body? Much of that must be laid at the door of her religious-wacko mom, Margaret, who, too, is brought up to contemporary speed with her fanatical fundamentalism.

Piper Laurie and Sissy Spacek were the original mother-daughter act in Brian De Palma's 1976 horror-cult flick. Lawrence D. Cohen, who adapted King's 1974 novel into that movie, also wrote the book for the musical version, which premiered with Barbara Cook and Linzi Hateley in Stratford-upon-Avon, England, in February 1988.

By the time the show settled into Broadway's Virginia Theatre a few months later, Cook had jumped ship, and Crazy Mama was played by Betty Buckley, who had been Carrie's gym teacher in the movie. In its current resurrection, Marin Mazzie and Molly Ranson carry on Carrie accordingly — but on a conspicuously smaller scale, with more book and newer songs.

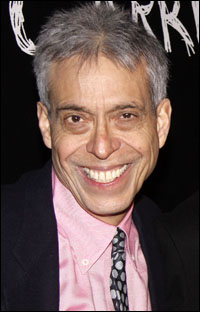

|

||

| Lawrence D. Cohen |

||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

There were lots of wake-up calls over the years — requests from regional theatres, high schools, colleges, even a BC/EFA benefit at Carnegie Hall — but the creative trio opted to let their sleeping dog lay rather than let the Broadway version loose among 'em again. But it was always in the back in their minds to return to Carrie some day and have another crack at it.

"Some day" happened about three years ago, over lunch. They were already working on something that resembled their original concept when they were invited to lunch by director Stafford Arima. At age 19, Arima had seen the Broadway show in previews, and it had haunted him ever since — in a good way. He sat down with them and went through the piece line by line, explaining what he would change. At the end of the eight-hour lunch, everybody was on the same page and gearing up for Off-Broadway.

"One of the fortunate consequences of all the lore and legend that has built up around Carrie," says Pitchford, "is that, when each of our actors was approached, they went, 'I love that show' or 'I have the pirated recording.' Within the theatre community, it has a reputation we sorta suspected was there, but, when people who are working in the business step up and say, 'Let me sing you the top of Act One,' you realize it has gotten to the people who matter. They all joined on because of their enthusiasm for what it is at its heart."

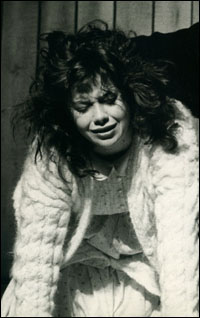

|

||

| Molly Ranson in the current revival |

||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

"If you went back and looked at that, Clive Barnes in The Post was every bit as much a rave. We would be running today, had Clive Barnes had his way in terms of the review. The Hollywood Reporter review — if our mothers had written it — couldn't have been better. But, in the myth of the past, all the reviews were terrible."

Anyway, Gore quickly points out, it wasn't even the reviews that sank the show: "Because Ken Mandelbaum never chose to interview the authors or anybody who was at the heart of that production, most people don't know that — three performances in — our producer, who was European and not experienced on Broadway, got nervous because he didn't get the Rich rave he wanted, closed his bank accounts, then got on a plane to Germany. The reason the show closed after five performances is that there was no payroll to pay anybody. Regardless of the perception — whether audiences didn't like it or the show wasn't doing well — the reality was he left town, there was no money to pay anybody, and it was too difficult — and too late — to find other producers."

|

||

| Linzi Hateley in the Broadway production |

||

| photo by Peter Cunnigham |

And who can fault them for going with their most prestigious offer? Terry Hands, artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, offered the facilities at RSC, his proven skills as a director and, head-turning most of all, $8 million. They said yes!

"It was irresistible as an offer," Cohen recalls. "He had 20 years experience directing and running with Trevor Nunn the RSC, so all three of us were thrilled at being a part of that esteemed company. He also spoke a really good game, and he was very, very smart. Then, we moved into the process of actually putting on the show."

The warning signs came early, according to Gore: "There are so many elements that just have to come together correctly in any play or musical, and we knew it was over when we saw the costumes, which were very abstract and looked like Greece. Not the show — the country. Every area, actually, did not resemble what we had in mind."

Carrie — in the hands of Terry Hands — became an unrecognizable, Anglicized aberration of their original concept. "He had all kinds of classical ideas about how this was to be done, and he decided it was a tragedy in 12 tableaus," Pitchford relays with a discernible grimace. "Tableaus," Cohen underlines archly, "is a word we no longer use."

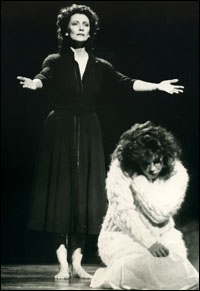

|

||

| Betty Buckley and Linzi Hateley |

||

| Photo by Peter Cunningham |

"Nor," notes Cohen, "had he gone to an American high school or understood what that was about. The word 'prom' didn't mean the same thing to him that it meant to all of us. It was a chasm. That we spoke English in common was the confusion."

As Hands molded his own Carrie, a helpless depression fell over the show's creators, individually at first and then collectively. "There were indeed moments when we'd be sitting taking notes at different parts of the theatre, and I'd get to a point where I just couldn't watch it and go out in the lobby," injects Pitchford with a slight shudder. "Then, two minutes later, Mike would come out, then Larry. We were able to stomach parts of it, but there were parts we just couldn't watch. Night after night, we'd find ourselves in the lobby, spending more time there than in the theatre."

Gore nods glumly. "It was frustrating," he sighs, "but we're not here to put blame on anyone. Projects happen the way they happen. You do a movie. Everything comes together. Sometimes it combusts and it's fantastic, and other times it doesn't. In this particular instance, there were too many things that combusted in the wrong direction for us."

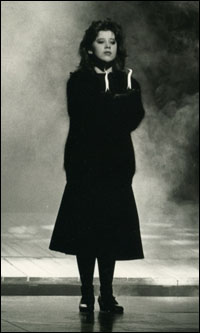

|

||

| Linzi Hateley |

||

| photo by Peter Cunningham |

"What happened when we came to New York was that the same division of the critics was palpable in the audiences in the weeks of previews and the week that we ran," says Cohen. "You'd hear roaring ovations and, just as loud, booing. None of us had ever been through that experience before. It was like being at a rock concert."

King or country is what it came down to, he simplifies. "What we really believe about this piece is that Stephen King is one of the great storytellers of the world and that story-story-story is what counts. Our new version is truer to Steve's book. The framework that Stafford thought was good turned out to be the initial framework that I had used to write the movie but that we didn't use in the De Palma version.

"The most emphatic thing I would say is it's a Carrie for today. The piece is not set in '70s or '80s. It's set now, and that's been the most informative aspect of looking at every single word, line and note of music in the piece. In great measure, it is now very much a book musical. We always felt that, and at last we have a director who feels the same way."

With Arima resolutely in their corner, says Gore, "it's come back to being the book musical we wanted. It was never conceived to be Evita or Les Miz as a through-sung piece. It was written with book scenes and with music scenes and other book scenes so that, when the book scenes were eliminated in order to become just musical tableaus, it put an onus on the show — but I think, more importantly, Terry ended up not supplying enough story that was really necessary. Now, the entire shape of the show is completely different. Larry went back to Square One again."

|

||

| Stafford Arima |

||

| Photo by Monica Simoes |

The newly found think-small mantra of the creators was encouraged by MCC Theater, Pitchford is happy to report. "I have to say that one of the greatest gifts was not only Stafford Arima stepping in when he did but also Bernie Telsey saying, 'Think about doing it with two saw-horses and a bucket — and, then, no bucket.' All of a sudden, those seeming restrictions are actually what energized us all over again because we were not going back to some place where we had been before with a singing chorus and some principals downstage. We have a very small ensemble, and their duties are broken up in a different way. Larry has completely re-imagined this story. It's a new beginning."

Gore agrees. "It has been utter freedom because we had to find solutions," he says, "not with money but intrinsically within the piece. People have asked, 'Why are you doing this now? Are you going to Broadway?' The reality is we're really looking at this as a chance to sit through the piece that we wanted. You don't know what's going to happen out there. All we do know is if we can sit through this piece from beginning to end and look at each other and go, 'Know what? That's what we had in mind' — regardless of what anybody else thinks — then it will all have been worthwhile."