*

The musical Evita is back on Broadway after a 29-year absence, stirring the hearts and minds of musical theatre fans, and perhaps raising the curiosity of history buffs eager to know more about the facts behind the pop classic.

Based on the life of Maria Eva Duarte de Perón, best known as Evita, the second wife of Argentine President Juan Perón, the musical — nominated for the 2012 Tony Award as Best Revival of Musical — is a window into Argentina's history.

Is the Andrew Lloyd Webber-Tim Rice musical historically accurate or an artful blend of reality and drama?

Here's an exploration of three historical aspects of Evita. One architectural — the Casa Rosada; one mysterious — the movement of Evita's body; and one biographical — the real Agustín Magaldi.

|

||

| Madonna in the film |

The Casa Rosada is the musical's most iconic architectural setting, the site of the opening of Act Two, where Evita makes her triumphant balcony appearance — in a Swarovski crystal-encrusted gown — to sing "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina."

The Casa Rosada, or Pink House, is the Presidential Palace, where Argentina's government is run. The current President is Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, a former First Lady, partly modeling herself on Evita. Still, it's not a woman's touch that made the building pink. Two legends explain the color. One says two rival political parties, one symbolized by red, another white, painted the building pink as a compromise. Another legend says in olden days the building was painted with cow blood that dried into pink-brown, which is the likely truth.

The Casa Rosada is built over the site of an old Spanish colonial fort and customs house. The President does not live here. She has an official home in Los Olivos in Buenos Aires' suburbs. In Evita's day, the home was in the Palermo neighborhood, where the National Library now exists.

|

||

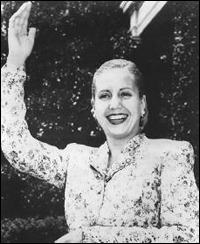

| Eva Perón |

Elena Roger, the native Argentine who plays Evita in director Michael Grandage's Broadway (and earlier London) revival, said that until the Vanity Fair March issue photo session held in the Presidential Palace, "I had never been inside the Casa Rosada," adding, "it was a very nice and emotional experience for me. A large part of the history of my country is in that place."

|

| The Casa Rosada |

|

||

| Eva Perón's tomb in Recoleta Cemetery |

||

| Photo by Michael Luongo |

The play's closing line mentions that Evita's body disappears for 17 years. Where did the body go? It's a long story beginning with its 1952 embalming in the CGT, the union building Confedercion General de Trabajo, by Spanish doctor Pedro Ara. The body was being prepared for the planned, never completed monument where Evita would be viewed like Moscow's Lenin. When Juan Perón was deposed in 1955, the body was hidden throughout Buenos Aires by military rulers who, though cruel enough to murder Eva's followers, still feared the body's spiritual powers and were too religious to destroy it. A romanticized discussion of the body's journey is in the 1995 historical novel "Santa Evita" by Argentine author Tomas Eloy Martinez.

In 1957, the body was sent to Milan's Maggiore cemetery, hidden under the name Maria Maggi de Magistris. In 1971, Evita, still perfectly preserved in a glass-topped coffin, was exhumed and given back to Perón, who was then exiled in Madrid. In 1973, Perón returned to Argentina for his second administration, but died on July 1, 1974. His third wife, Isabel, became President, and on Nov. 17 that year, brought the body back. It's said she conducted séances over it, begging the spirit of Evita to help her administration. That didn't help; in 1976, Isabel was toppled by a military coup. Evita was returned to her family, who placed her in Recoleta Cemetery in a tomb belonging to her father's family, the Duartes.

Dr. Gabriel Miremont, the curator of Buenos Aires' Museo Evita, said, in essence, Evita died two deaths, first "her untimely death at age 33, devastated by cancer and then, by a second death, the awful journey that her body took."

Roger said, "Once I knew I was going to play the role of Eva Perón, I did a lot of research, which included visiting her tomb at Recoleta. It has the most artistic and moving tombs I have ever seen." She recommends every tourist see them, adding, "After the chaos following her death — Perón's exile and the disappearance of her body — it is nice to see that she is now laid to rest in a simple and peaceful place."

Argentines have a thing with worshiping the dead bodies of political leaders, and Evita's not the only one who had trouble resting in peace. Violent riots marked the moving of Juan Perón's body in 2006 to a new tomb in San Vicente, in the suburbs of Buenos Aires, to a country home he and Evita shared. A companion tomb was built here for Evita, but the family, and the Eva Perón Historical Foundation, run by Evita's grandniece Cristina Alvarez Rodriguez, will not allow her to be moved again. Perón's body had also been violated, something Michael Cerveris learned researching his part, too. "His hands, apparently, were cut off and stolen from his tomb," Cerveris said, citing his research at the Juan Perón National Historical Institute. "One theory being that someone believed that they could be used to open a secret Swiss bank vault."

|

||

| Agustín Magaldi |

Poor Magaldi! He's made fun of in Evita — as a middling talent and a stepping stone billed as merely "the man who discovered her" — but in reality he was a great tango singer, second only to iconic Carlos Gardel within Argentina's crooner pantheon. Like Eva, he also died young, at 39 in 1938, and could not have been singing in 1944 during the Luna Park concert fundraiser scene in Evita (where Eva meets Juan, in the musical). Even though the play that does not match the history, actor Max Von Essen said he wanted to respect his character, explaining that he sought to sing "On This Night of a Thousand Stars" more confidently in its reprise, as someone who had matured as a singer. We first meet Magaldi as a younger singer in a rural cafe in Junin, with young Eva already his lover.

Of course, Evita probably never came to Buenos Aires with Magaldi to begin with. There's no record of Magaldi playing in Junin around 1934. Some historians believe Evita made up her relationship with Magaldi, even possibly carrying around a letter of introduction from him. After all, just like starlets of today, association with someone more famous always helps a career. How else was the 15-year-old Maria Eva Duarte going to convince Buenos Aires of her star quality?

|

||

| Max von Essen |

||

| photo by Richard Termine |

He added, "The role of a historical museum is to present to the public the true history." Miremont invites admirers of the play Evita who want to learn more about this remarkable woman to visit museoevita.org, or the museum itself when in Buenos Aires.

If that's not an option, you're still in luck. According to Miremont, the Museo Evita will also have a traveling exhibition in New York and Washington in September, featuring Evita's clothes and other personal objects. So there's no reason to cry for anyone.

(Michael Luongo, the author of "Frommer's Buenos Aires," is a self-proclaimed "Evita Freak" who's been writing on and living part-time in Argentina more than 12 years. Find him at www.misterbuenosaires.com and www.michaelluongo.com.)