*

When Bill Irwin was announced as The Fool in the Public Theater production of King Lear starring Sam Waterston, a few journalists around town went through a two-tiered response. The initial reaction was surprise at an unexpected piece of casting. But that soon mellowed into an "Of course." Who better to play dramatic literature's most famous fool that this acting generation's most preeminent stage clown? Why didn't someone think of this before?

Turns out, someone did. Irwin himself, in fact.

"I've been waiting to do it since I was 15," said the actor. "It was the first Shakespeare play I ever read. I was going to a school in Belfast as an exchange student, and it was on the curriculum. I'm not sure I've read any Shakespeare play so prolongedly since. I love the play. It's the weirdest play. It's great, and yet it's this ramshackle, stapled-together thing. I've been hoping for a long time to play the Fool, and also hoping the chance would never come around because it's full of challenges."

The chance came because Irwin made it come. "I heard [the Public] was doing the play and Sam was doing the role and I literally begged [Public artistic director] Oskar Eustis to be part of the week of readings that director James Macdonald conducted back in February." He got the assignment and worked the week for a pittance. "It was like Eden in a tiny dusty room on the upper floors of the Public Theater." When he was offered the part in the production, however, he almost passed on his dream role. He wrote Eustis and Macdonald heartfelt notes explaining that "the economics of this actor's life won't allow it." But then he reconsidered, and grabbed the role. "I realized I had to do this thing."

Irwin makes a very showy entrance in Macdonald's production, which is relatively modest in scale, given the tragedy's monumental, sprawling reputation. Scenically, the first act is dominated by a stage-wide, grey, chain curtain. Through this drab wall, Irwin's clown enters dressed in a billowing, sun-yellow satin costume, high cap on his head and ukelele in his hand.

|

||

| Irwin in rehearsal |

||

| photo by Nella Vera |

Irwin has prepared for the role by immersing himself in the play's history. The Fool in King Lear was first played by Robert Armin, who became the chief comic talent in Shakespeare's troupe after the departure of actor Will Kempe. He also originated other famous Bard roles, including Feste in Twelfth Night and Touchstone in As You Like It. Armin is widely credited by scholars with elevating the fool parts in Shakespeare's plays to a level of high art.

"For decades I labored under what I thought was a comfortable assumption — a comfortable delusion, I'm told now — that a young boy actor would play Cordelia and that same actor would play the Fool and then go back to Cordelia," Irwin admitted. "It feels like the text is designed that way. But James Macdonald tells me no. It was Robert Armin, who apparently ad-libbed a lot."

Eustis believes that Irwin brings a bit of both Armin and his predecessor to the role. The Fool in Lear "is darker and more ironic, less physical, more verbal," than other Bard fools, argued Eustis. "Bill does all that. But he also has the classic physical clawing. I think of it as Will Kempe territory. He's both a clown and a good actor. He gets the goofiness of the clown combined with the spiritual desolation of this particular fool."

For Eustis, Irwin's facility with Shakespeare's language was not a surprise. He had witnessed it first hand, when Irwin playing the title role in Richard III in a Public reading years ago. "I got the inside sight on how good Bill can be with language," he said.

|

||

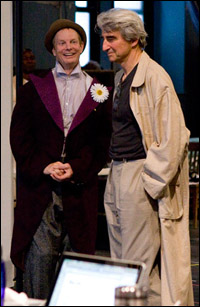

| Irwin and Sam Waterston in rehearsal |

||

| photo by Nella Vera |

Those witty turns of telling verse reward an actor's efforts, but are initially difficult to wrap one's tongue and mind around. Take, for instance, the Fool's "prophecy," uttered on the blasted heath:

"When priests are more in word than matter;

When brewers mar their malt with water;

When nobles are their tailors' tutors;

No heretics burn'd, but wenches' suitors;

When every case in law is right;

No squire in debt, nor no poor knight;

When slanders do not live in tongues;

Nor cutpurses come not to throngs;

When usurers tell their gold i' the field;

And bawds and whores do churches build;

Then shall the realm of Albion

Come to great confusion:

Then comes the time, who lives to see't,

That going shall be used with feet.

This prophecy Merlin shall make; for I live before his time."

"The prophecy is really wedged in the middle of the action," said Irwin. "I almost actively begged James to cut it. But he always enigmatically held back. He said, 'No, there's a reason that's in there. You'll be glad that's in there.'

"There's always that danger you have when you do something like this, where you feel you want to help out the old Bard. But you have to resist that."