*

Georgia Stitt, a jack-of-all-trades with an influential voice amongst contemporary songwriters, is a composer and lyricist who has also worked as a music director, arranger, pianist, coach and educator (and also dabbles in performing, having recently been seen in "The Sound of Music Live!" on NBC). She wrote the original musicals Big Red Sun (Arlen Award 2005 with playwright John Jiler); The Danger Year (with Jamie Pachino); Samantha Spade: Ace Detective (for TADA! with Lisa Diana Shapiro); Mosaic (for Inner Voices with Cheri Steinkellner); and The Water (with Jeff Hylton and Tim Werenko); and has released three albums of her music: "This Ordinary Thursday: The Songs Of Georgia Stitt" (2007), "Alphabet City Cycle" (2009) and My Lifelong Love" (2011).

Her songs and arrangements are represented on the solo albums of Susan Egan, Lauren Kennedy, Kate Baldwin, Robert Creighton, Stuart Matthew Price, Caroline Sheen, Daniel Boys, Kevin Odekirk and composer Sam Davis, as well as several "Broadway Cares" albums. Her choral piece with hope and virtue (using text from President Obama's 2009 inauguration speech) was featured on NPR as part of Judith Clurman's "Dear Mister President" cycle, and her most recent orchestral piece, Waiting for Wings, co-written with husband Jason Robert Brown, was commissioned by the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra and premiered there in 2013 with conductor John Morris Russell.

She is on the theatre faculty at Pace University and is the composer-in-residence at Pasadena Presbyterian Church. For more information, visit GeorgiaStitt.com.

For a performer, what is most important to a music director? Vocal technique, range?

Georgia Stitt: I can't speak for all music directors, but to me the most important thing an actor can do is know how to act through a song without compromising its musicality. Obviously I am wooed by actual musicians — performers who can read music, hold harmonies, sight sing and understand the gifts and limitations of their own voices, but when it comes to casting a show those things all have to work in tandem with the acting or they are wasted. I don't care what your highest note is; I care what your biggest choice is, and if you pull it off with grace and commitment I am your biggest fan. Can you speak about etiquette when approaching the accompanist, establishing tempo and being clear on your cuts?

GS: Be confident about what you need from the accompanist. Wishy-washy requests make you seem unprepared. Respect that the accompanist is there to help you and can oftentimes even elevate the level of your audition. I know that sometimes you get stuck with a bad pianist, and I know that it sucks. Believe me: everyone in the room knows when the pianist is bad. When that happens, the creative team's day is even worse than yours is. But sometimes the pianist is great, and you have a fabulous musical scene partner in the room. Offer up some tips to make the sight-reading experience go more smoothly — say, "This is my tempo" or "I've highlighted the key change just after this page turn" or "You'll see I've cut from here to here." But assume that they know the song and you're just giving them a moment to understand about how you do it. And then say thank you, and hope for the best.

Depending on the audition, is it best to ask the creative team what they want to hear? Do you run a risk by picking the song yourself?

GS: I would never advise you to say, "What would you like me to sing?" It puts too much pressure on the creative team to do your work for you. We do usually appreciate when you say, "I could either sing [song title] or [song title]." But if we say, "Whichever you prefer" or "Just show us who you are," then by all means make a choice, and go for it. Those of us behind the table want you to be confident and comfortable. If you sing the wrong song, but you sing it beautifully, I have still learned a lot about you as a performer, and I will then ask to hear something more specific.

| |

|

|

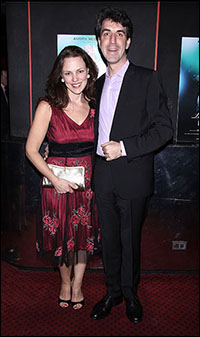

| Stitt and husband Jason Robert Brown | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

GS: It really depends on the piece. If your vocal liberty shows me that you understand the style of the music and the context of the moment, and it feels true to the character and the storytelling, then by all means I'm open to it. If your vocal liberty feels self-indulgent or gratuitous, then it will probably piss me off. Don't give me a chance to assume that you just didn't learn how it was supposed to go.

For aspiring Broadway music directors and conductors, what is the best way to break into the industry?

GS: Meet people and do consistently good work. We all need to know who the up-and-comers are. Several times a year, I hire some kind of assistant for something, and I'm usually asking my fellow composers and music directors if they know any young talents they might recommend. If you've done a great job for my friend's project, that recommendation is worth more than anything you might have written on your resumé. My first jobs in NYC were music directing in high schools and children's theatres, playing for acting classes, doing Finale work for more established composers, subbing in pits and playing auditions. The more skills you have (sight-reading, music copying, improvising, coaching, being nice to people) the more opportunities you will have to build your network of contacts. Nothing is more valuable in this business than a good reputation.

As a composer and music director, can you talk about getting representation? Does a wide-ranging skillset work to your advantage?

GS: I didn't need a lawyer until suddenly one day I did. I had been offered a music-directing contract that seemed sub-standard to me, and I showed it to a more established music director and said, "Is this fair?" He said, "Oh, yeah, you need Mark Sendroff." So I hired Mark Sendroff, and he has represented me ever since. I now also have an agent for my writing, and for a few years I also had a manager. The most important thing I have learned about all of that is that you have to generate your own work. Agents can certainly introduce you to people and throw your name into the mix for projects you might otherwise not see, but in order to start representing you, they have to have something they can sell. More important than anything else: keep creating your work. Don't get so caught up in selling your product that you forget to make your product.

How do you get agents to come see or hear your work? Do you submit demos, invite them to concerts?

GS: The last time I hired a new agent, I asked around among my colleagues and there were three or four agents who seemed to handle a lot of the writers in my category. Once I reached out to them (again, no cold letters — all with the recommendation of someone who knew me well), I sent a copy of my resumé and some of my CDs, and I asked for an introductory meeting. In that initial meeting, I was interviewing them as much as they were interviewing me. I have never had success sending out a cold invite. No matter what it is I'm asking from someone, I try to find the way to link my request to a detail that means something to them personally. I mention our mutual friends, theatres we may have in common, work of theirs that impressed me. It's not manipulative; it's just more fun to work with "friends of friends" than with strangers.

| |

|

|

| Stitt at a recent anti-piracy event | ||

| Photo by Donald Bowers/Getty Images |

GS: You have to learn how to say no. If you are capable of doing lots of things, you will be asked to do lots of things. I really do often use the rich/famous/happy model. You know the one — any potential job needs to fulfill two out of those three categories. It could make you rich and famous, but not happy; it could make you rich and happy, but not famous; or it could make you famous and happy, but not rich. If you're not doing it for money, exposure or personal growth/satisfaction, then why are you doing it? Say no to things that aren’t worth your time. Say no to things that demand too much of your sanity. And say yes to the things that allow you to work with the people who can help you advance to the next level. Work up. Working with people who are exactly like you will not result in much growth. Work with people who inspire you and can teach you something you didn't already know.

As a follow-up to that question, can you talk about the challenges of leaving New York City for regional gigs? Is it worth it to head out of town?

GS: It is worth it to go out of town if you are going to grow from the experience. Some of my favorite collaborators — directors, actors, choreographers — are people I met when I was in my twenties and traveling out of town for nearly every job. We all grew up together, and now we have years of history and trust that feed us as our generation becomes collectively more successful. If I need to hire someone, I'm either going to call the person I've known and trusted for 20 years or I'm going to hire the person I respect from afar and am dying to work with. Now, years later, I've got a husband and two kids, and it's much, much harder to get me to leave town. Still, if the opportunity or the paycheck or the music is great, I will go. But I'm grateful that I established a lot of those relationships before I had kids, because it is very hard to be away from my family.

Also, for an artist as such, do you schedule or prioritize your time? How do you balance writing with gigs that pay the bills? Do you set aside special time to write or does inspiration lead the way?

GS: If I allowed inspiration to lead the way, I would never write. I write because someone is waiting for me. That pressure might be coming from a collaborator or a theatre or an actor or a producer, but I write because it would be irresponsible for me not to write. I do try to schedule "writing days," where I don't make lunch dates, and I don't run errands, and I don't see shows in the evenings. I am most successful when I have big chunks of time, so I can go deep into the world of the material. But because of real-life responsibilities, I have to balance those days with the more realistic and over-scheduled days of work and family. If I am truly on deadline, I really have to shut everything else down.

| |

|

|

| Stitt and Brown at opening night of The Bridges of Madison County. | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

GS: I think the younger composers today are having so much success by booking themselves into concert venues and video recording the performances for YouTube. People then find their material when they search the web. When I was starting out, I gave my songs to my friends and then hoped they would program them in their concerts and record them on their albums. I have a few singers (Keith Byron Kirk, Andrea Burns, Kate Baldwin, Susan Egan) who learned everything I wrote and I will forever be grateful to them for believing in my work before I had any kind of clout. I think it's just a fluke that I never made a big impact on the cabaret scene. I would have been happy for that to happen, but my route turned out to be more about one person and one song at a time. It has been very slow and steady for me.

What about releasing an album of favorite songs? How does one go about successfully releasing an album?

GS: Well, yes, that's the next logical question. I think the single biggest leap forward my career has taken was the year I released "This Ordinary Thursday," my first album of songs. I made the recordings a few at a time, as I could afford the sessions. Then, when I had recorded enough material, I hired record producer Jeffrey Lesser to come in and mix the tracks into a cohesive whole. That was a huge job for him, and I wouldn't recommend making an album that way, but at the time it was the only way I could afford to do it. I love making albums and would even say that being in the recording studio is my favorite part of my job. But it's expensive to make recordings, and it's hard to sell albums, so you really have to invest in a solo album as a loss leader against your future career. For me, it has been a move that was hard to justify financially but has paid off professionally. My albums are my calling cards. I now give them to people and say, "This is me; this is what I sound like."

What interests you about performers? How do you go about finding the perfect match for your material?

GS: Again, it's just me, but I love a performer who uses his or her voice as an instrument. I am excited when an actor knows how to make music — teasing me with phrasing or dynamics, locking into a rhythmic groove, building a song slowly over time. I love actors who know they are powerful actors, who are really smart and trust their instincts. I find insecurity tedious. We all have it — really, we do — but you have to figure out how to leave it outside the room where you're doing your work, and I think that's the biggest challenge we all face. I keep lists of people I want to work with, and when I'm staffing a reading or hiring for a concert or making a demo, I take a deep breath and reach out to my heroes and ask if they'd like to sing with me. That's where my insecurity comes in. But if you don't take the risk, you never move forward, and really, that's no way to live.

Talk to us about the risks of taking on completely new pieces — as a writer and as a creative. What excites you, what is the challenge, and what makes you feel apprehensive?

GS: Well, everything I do is a new piece. The excitement comes from making something from nothing. The thrill of completing something — a new musical, a new album, a new song cycle, a new choral piece — is that writing is so much about the tiny little details. You want the rhymes to be perfect and to have meaning. You want the harmonies to be fresh and emotional. You want the articulations in the band parts to be clear, and you want every person performing to feel like you have given him/her something important to contribute to the whole. And then at some point, you get to step back and see what the sum of all of those details has become. The whole thing has its own personality, its own voice, its own statement. The risk comes when you try to sell it. If you can say the things you meant to say and people still want to come hear it, then you have succeeded. But you can't think about that when you're trying to write the musical phrase that sweeps into the key change and the return of the vocal. You just have to write it.

(Playbill.com staff writer Michael Gioia's work appears in the news, feature and video sections of Playbill.com as well as in the pages of Playbill magazine. Follow him on Twitter at @PlaybillMichael.)