*

"Oh, my God! What a strange coincidence!" exclaimed Frank Langella in a soft yet still mellifluous gulp recently when asked to affix his mark to a theatre program.

Once upon a time, before there was Lincoln Center Theater, there was The Repertory Theater of Lincoln Center, and in its 1968-69 subscription season he starred in a William Gibson play called A Cry of Players, cast as a callow, 21-year-old William Shakespeare, who is married to the eight-years-older Anne Hathaway (Anne Bancroft) but drawn instinctually to a higher calling than conventional domesticity.

It played in rep with King Lear, the play that Langella is just getting around to performing at the Brooklyn Academy of Music's Harvey Theater now through Feb. 9. On alternate nights at the Beaumont back then, Lee J. Cobb reigned supreme as King Lear, the monarch who, to his own ruination, made poor judgment calls on his three daughters. Langella looked in on the performance occasionally, never imagining 46 years later he'd be gingerly negotiating his way down that same narrowing path.

The autograph request went to the back-burner while Langella leafed through the pages of his past with leisurely affection. "Annie's gone — so many of these people are gone now," he said sadly, perusing. "Philip Bosco was in Lear?" he was startled to note on hitting the bio section. "Let's see what picture I was showing off then..." The publication, more Life-size than Playbill-size, ran cerebral supporting texts on Lear, Shakespeare and Gibson, who, by this point in time, had already given Broadway his best: Two for the Seesaw and The Miracle Worker. Commanding much of Langella's attention was a lavish five-page pictorial feature, "Kings of Lear," showing many of the acting greats who had done their thespian push-ups in the part — Henry Irving, Laurence Olivier, Alec Guinness, Michael Redgrave, Louis Calhern, John Gielgud, Orson Welles, Charles Laughton, Paul Scofield, Donald Wolfit, Morris Carnovsky, Frank Silvera, even Tommy Rall doing the "King Lear Ballet" from Café Crown — and now Langella, 76 on Jan. 1, finds himself in this company of kings.

He was brought to this precipice by Duncan Weldon, the London producer who once ran the Chichester Theatre Festival, and Jonathan Church, who runs it now. They caught Langella in Tony-nominated form two seasons ago in Man and Boy and, afterward, invited him to do Lear in Chichester. "It was extremely flattering for an American because they'd never had an American there to head up a company," Langella said, "but I told them I didn't want to do it — that I had a notion in my head to play a great female character. I've always wanted to play a great female role, and I told them a couple of ideas I had in my head, but they were not sure how that would work on their audience. I think what they were thinking was I wouldn't sell tickets unless I did one of the great Shakespeares, so I said, 'Well, then I'm going to pass.'"

| |

|

|

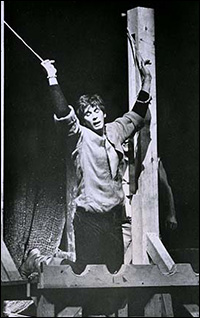

| Langella in A Cry of Players | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

The notoriously difficult-to-please English critics threw caution to the wind and hats in the air last fall praising Langella's performance, which they said was full of old-school barnstorming. For someone who loves language and relishes words, it was a feast.

Six-foot-four of crumbling regal-bearing, which he wore in his Tony-winning/Oscar-nominated role of Richard Nixon in Frost/Nixon, works well for Lear, too.

"I actually think that Nixon has been a good primer for this. I didn't think about it before, but, if I look back at the roles I've played — even as a young man — I was always attracted to epic, tragic characters. Always. I'm not a regular guy. I never have been. Ever since I was young, I was always attracted in movies to Cagney on the top of the building saying 'Top of the world, Ma' or Robinson dying in the gutter saying, 'Is this the end of Rico?' Those characters always thrilled me. They're the ones I wanted to be."

Langella takes great pride and care in trying to sum up his characterizations into a single look, which then becomes poster art for his plays. His troubled Sir Thomas More, which was used to promote his 2008 revival of A Man for All Seasons, echoed an expression he found of Jimmy Carter in a photography book. His Lear, looking blackly into the abyss, followed 50 or 60 full body shots of him in the mud or him strolling in a vast open forest. "I didn't like any of them," he admitted. "I thought they were pretentious — not real, not commercial, somehow not emotionally right — so I said, 'Just pick up the camera, and I'm just going to sit there and think of nothing and go into a very dark place.' The guy took it. It went click, and he turned it around and said, 'That's it.' We all did — five of us in the room — everybody went, 'That's it!'"

| |

|

|

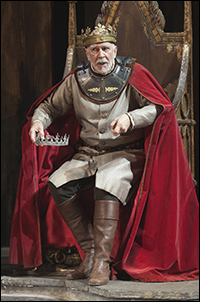

| Langella in King Lear. | ||

| Photo by Richard Termine |

"When playing Lear, you need to play it in 12 separate one-act plays. You can't play it as one play. You have periods of time when you're off, and the things that happen to you as a character offstage are extraordinary. When you leave the audience in one scene and don't come back for 15 minutes, major events happen to you, so you must bring on with you all the things that are required for that scene. The last four scenes Lear has in the second act are entirely different, like four separate plays."

Incredible as it may seem, given his remarkable vocal instrument, King Lear is just Langella's fifth (!) Shakespeare. "Well, I didn't want him," he said with a slight shrug, "and it's my loss because I think I'm enjoying this — as much as you can say 'enjoy' about Shakespeare. You don't 'enjoy' him as much as you're profoundly challenged.

"But I've had a lucky career. I've played everything — from Williams to Miller to Racine to Shaw to Moliere to Coward to Anouilh — great playwrights and great parts.

"But I don't have a favorite role. I have a whole bunch of parts I love playing when I played them. I loved playing Present Laughter, and I certainly loved playing Salieri for a year in Amadeus — that's just one of the great showy roles — and I actually liked young Will Shakespeare as an actor. It was a great part to play. And, of course, I love Dracula — a one-time-only experience. It was like being Elvis Presley for a year." Next, in his year of Lear, he plans to explore that feminine side of the ledger, which spooked the Chichester execs. "I've always been jealous of the great female roles," he admitted. "When I see an actress biting into some wonderful Medea, I think, 'Gee, I'd love to be able to do that.' I always wanted to explore that in myself. Mind you, this would be a monster woman. I don't think I could get away with a delicate creature."

PHOTO ARCHIVE: Celebrating Three-Time Tony Winner Frank Langella