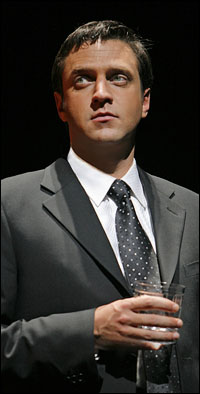

Doyle's new production of Merrily We Roll Along, Sondheim and George Furth's musical about a group of friends who navigate the ups and downs of love and success, also employs actor-musicians to tell its story. This production is debuting at Cincinnati's Playhouse in the Park, where the director's Tony-winning actor-musician revival of Company also premiered prior to a 2006 Broadway run.

Playbill.com caught up with Doyle just prior to opening night.

The Cincinnati run isn't your first crack at Merrily We Roll Along; you staged the piece at the Watermill Theatre in the U.K. before, correct?

JD: Yes, I did Merrily about three or four years ago. It was at the Watermill Theatre where I did Sweeney Todd and where I've done a lot of work developing the actor-musician thing. When [Playhouse artistic director] Ed Stern asked me to do something here at the Playhouse in his final season, I thought, "I'd really like to have another go at Merrily in an environment with a slightly bigger resource." I love working at Watermill, but I was interested in the possibility of exploring it again. So, I asked Steve [Sondheim] if he would be cool with me doing it in Cincinnati, and he was. So that's why it happened, really.

Since its Broadway debut in 1981, Merrily has undergone various rewrites. Did you pull from different versions or go back to explore the original? JD: No, you know I could have tried to go back and start with "The Hills of Tomorrow" like the original, but I didn't intend to do that. That by its own nature kind of dictates the nature of the age of which you play the show, in terms of the cast, and I didn't want to do that. So, I happily have explored the latest version that James Lapine was involved with.

Everybody who has ever approached this piece, it seems to me, with any seriousness, has made their own edits and found their own way through it. Steve is very open to that, but is obviously very loyal to George's original material. I haven't rewritten anything, but I've made some edits. Partly because I'm doing it with actors who play instruments. I'm doing it with 13 people, so by its very nature that means you have to do certain things to expedite the storytelling. I don't think I trimmed it anymore than it's ever been trimmed. Because it's done with 13 people, that inevitably means that some things get trimmed because there's no doubling up of actors and characters, because you can't play two people and not change costumes.

| |

|

|

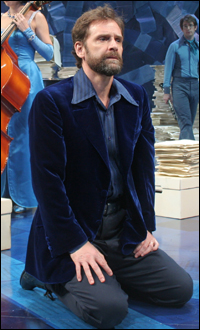

| Malcolm Gets in Merrily We Roll Along. | ||

| photo by Sandy Underwood |

JD: People asked me, "Do you think you've solved Merrily?" I don't know. I'm not the person that could ever answer that. I don't have such big problems with it. People say that the characters aren't all that likable in the beginning, I mean, a lot of people aren't very likable. I feel that we have a series of characters here right from the start that people really care about. What I can tell you is that this production of Merrily goes straight through without an intermission. For me, I like that for the piece. It is a series of years going back and I was thinking, "Why stop? Why suspend that, why not just keep the journey going?" So, it's an hour and forty-five minutes with no intermission.

Merrily is truly a musical about music. What has moved me in your other actor-musician productions is that having actors also play instruments brings out subtext and new connections between characters that might not have been apparent before. What drew you to use this for Merrily?

JD: I'm kind of protective of it as a form because I was very much part of its development, no arrogance intended. I often read, "Oh, John Doyle, he's the person who does shows with actor-musicians." The reality is that I've done 20 of them out of a career of 250 shows, but it's better to be known for something than nothing at all, I suppose. [Laughs.] But it's very important to me, as the years have gone on in working with this style, that there must be a good reason for doing it. When I first did it in the U.K., it was, of course, financially driven. I was working in theatres that didn't have any resources. But now it's in situations where I can have more choices and I only really try to do it if there's a real point and there's something to say.

Now, if I look at Merrily as a play, it has key lines about music. Franklin Shepard has a line, "If I didn't have music, I would die." To me he is saying, "Music is everything." And, he is a songwriter, therefore a man who makes music, and his songwriting is being taken away from him by 15 minutes of fame and the lure of success and winning awards. I've tried to play with the tension of those issues and at the same time celebrate that the music is completely in the room.

| |

|

|

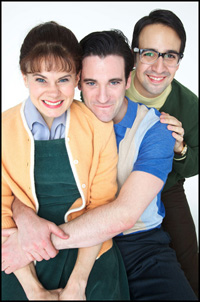

| Celia Keenan-Bolger, Colin Donnell and Lin-Manuel Miranda starred in the City Center production | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

JD: Scott Pask has done the set. The set is made up completely of music. There's no furniture; it's piles and piles of music manuscript. Actually, it's piles of the original score of Merrily We Roll Along, which Steve said I could graciously copy. The walls are also covered in music and the lights that hang above in globes are covered in music, so you know that you are in a world where music is the heartbeat of the piece, not just because it's a musical, but because it's about musical collaboration.

For the staging, the musicianship totally happens in the belly of the room. The central thing in the room is a grand piano, and music happens totally in the middle of the action, much more so than anything I've done before. I was nervous about that because when you place the instruments right in the heart of the story, you give yourself a number of challenges because somebody playing an instrument is such a beautiful thing to look at that it can upstage the central action if you're not careful.

The characters in Merrily have a decades-long journey. It's been cast with actors at various points along that age spectrum to varying success. Where did you start?

JD: I wanted people who would completely understand emotionally what it was to be 40, 30, 20 – people who had lived through those things emotionally. I didn't want to be the only person in the room saying, "Well, when you're 40 this is what it will feel like." [Laughs.] You have a situation where, I think this is the first time, where it's been played by three people who are at the older part of the way you can play the role. And that was an absolutely deliberate choice. I find that watching three people who are mature people playing 20-year-olds very touching, especially if they don't change costume all night. They can't – they're playing for each other all night.

| |

|

|

| Raúl Esparza in the Doyle-directed Company. | ||

| photo by Paul Kolnik |

JD: Malcolm Gets [Frank] is on piano. Daniel Jenkins [Charley] plays trumpet, and he also plays some of the stringed instruments. Becky Ann Baker [Mary] is basically the percussionist of the evening, and she also plays some double bass, which is rather divine. You could argue that Charley doesn't have to play because he's the person who writes the words. But when you start to do that to this work, it sticks out a mile somehow. It's always better in the end that everyone does something because it's kind of the nature of the beast, you know, that it's a group of players telling the story rather than, "My character isn't an instrumentalist." It doesn't really carry through.

Your collaborator Mary Mitchell Campbell has been along the journey with you since Sweeney Todd. How do you begin to map out the orchestral charts and the show itself?

JD: She and I will talk through each song and talk about the mood I want the song to have. Then I sort of give her an indication of who might be able to play for each song. Then, she'll come back to me with a sketch of the orchestration and I'll say, "Oh, that person could play," or "This is the person who really needs to be at the piano because the song could be more about them." She does a brilliant job. We go into the rehearsal with the orchestrations and then it is a logistical challenge to figure out: "OK, you're playing a flute line there and a flute is an instrument that you can put down, so I need you in this transition to play those six bars; put the flute down, move that piece of furniture, pick up the flute again and walk to that other place." It's a geographic challenge. I love that, of course. I happen to be working on the material of a man who loves puzzles, so it's a great puzzle in its own right and I guess the piece itself is such a puzzle in terms of its backwards journey. Actually, I think that way of working suits it rather well.

Your cast always makes it look effortless. JD: What it does demand, that the actors love, I think, is a tremendous amount of repetition. You're asking the actors' mind and body to learn physical things, vocal things and often to be playing on an instrument a totally different line against what they're doing vocally. Somebody could be playing the violin and singing a vocal line at the same time and they're two totally different things – and they're walking.

When you look at a script, do certain characters strike you as being paired with a specific instrument or does the actor's preset skill determine that?

JD: First and foremost what's important to me is, "Can they act?" This is really something actors should do. This is not about taking jobs away from classical musicians. It's not about marginalizing in any way. It's simply its own form. I get slightly irritated when people call it a concept – it's the means to the end. I do think sometimes, "Wouldn't it be nice if this character played the cello, if they feel a mellow character, so they should play the violin or cello, maybe. Do you really want that young pretty girl blasting the trumpet?" And, maybe you do. But what I end up doing is asking who is the best person for the role. That way you get people who can make the instrument look like it belongs to the character.

As you mentioned before, people may tend to label you as that actor-musician director, but your work has clearly struck a creative nerve.

JD: Look, now Once is going to Broadway, and they play instruments. I'm thrilled about that. It's no longer that John Doyle thing. People are starting to realize that it's a language of its own; it's not just a cheap way of making musicals. It's just a different way of making musicals.