*

Sheldon Harnick, the Pulitzer Prize- and Tony Award-winning lyricist (with composer Jerry Bock) of Fiddler on the Roof, Fiorello!, She Loves Me, The Apple Tree and The Rothschilds, is appearing March 8-12 as a special guest of Tony nominee Kate Baldwin at Feinstein's at the Regency. The show is called She Loves Him, and it's Baldwin's musical tribute to the 86-year-old lyricist. Expect favorite tunes, plus early Harnick specialties.

It seemed a perfect time to sit down with the master lyricist. Mervyn Rothstein, Playbill's A Life in the Theatre columnist, recently talked to Harnick about everything from leading ladies to leading men, his favorite current musicals and his least-favorite current musicals, his views on the state of the art and his plans for his future in the theatre. (Harnick will also be the subject of Playbill magazine's A Life in the Theatre column in the coming months.)

Here is some of what Harnick had to say:

ON LEADING LADIES Bea Arthur (Fiddler on the Roof): Bea was an extraordinary performer, an extraordinary comic presence. But when we hired her to do Yente, at all of her auditions (Jerry Robbins, the show's director, saw everybody three or four or five times), we always said she's wrong for this role — she's New York today, she's not Anatevka at the turn of the 20th century. Nevertheless, it was the strongest performance of anybody we saw. So Robbins said she's the one I want, and we hired her. And we told her there would be very little singing for her to do. But she became relentless. She used to follow me around the theatre and tell me about ideas, something that Yente could sing in this scene, or Yente could sing in that scene. So as much as I admired her as a performer, I began to dread seeing her, thinking I would have to fight her off again.

|

||

| Hal Holbrook and Barbara Harris in The Apple Tree. |

||

| photo by Friedman-Abeles Photographers |

Barbara Cook (She Loves Me): Because of the nature of the shows [like The Music Man] that Barbara Cook had done before we worked together, I had this image of her as being this kind of sugar and spice ingénue. Jerry Bock and I played the score for her and she accepted immediately, and we were thrilled. And then she began to come to the auditions with us, and I would sit next to her, and I got a whole different picture of Barbara Cook. She was never mean, but she was always very candid in her opinions of the performers. And I thought, wow, this is a spunky lady. It was borne out through the years — she is absolutely candid. That's one of the things that she brings to her performance — she is absolutely honest in everything she does.

Jill Clayburgh (The Rothschilds): I had a crush on Jill. She was adorable. The only thing I remember about Jill though was that she had done Off-Broadway — she had never been in a long-running show. And she told us once, with this astonished look in her eyes, "I have to buy additional makeup."

LEADING MEN

|

||

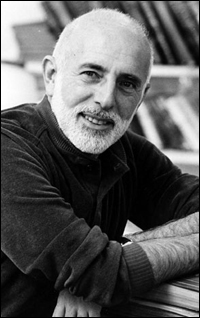

| Zero Mostel in Fiddler on the Roof |

On the other hand, he did things onstage, he took liberties. Sometimes cast members would turn to give a line to him and find he was not where he was supposed to be. It made it very difficult. At one point, a theatre critic from a Kentucky newspaper came to New York, saw the show, went back and wrote a column that said this show is wonderful, but wait until Zero Mostel is out of it, because as funny as he is, he's distorting the scenes. And Harold Prince [the producer] composed a letter to Zero which couldn't have been more politic, and he had Joe Stein [the librettist] and Jerry Bock [the composer] and I read the letter, and we said yes, this is so delicate. And he sent it to Zero. What it said basically was that we understand that a man of your creative abilities gets tired of doing the exact same thing every night. All we ask is that when we feel that perhaps you've gone over the line we should be allowed to discuss it with you. He hit the ceiling. He said, "You don't tell me how to do this show." He was very difficult. But I must say that although some of the things he did bothered us, they never bothered the audience. They loved him no matter what he did.

Alan Alda (The Apple Tree): He is such a generous man and a wonderful performer. There are things in The Apple Tree which I didn't write which he just ad-libbed, and they went right into the script. What I didn't realize at the time was that he had the capability of being a very fine writer. I think he was happiest when he won awards for episodes of "M*A*S*H" that he had written.

DIRECTORS

|

||

| Jerome Robbins |

George Abbott (Fiorello!): He looked very aristocratic, and it was a long time before I dared to call him George, and usually that was when my emotions ran away with me. He was a man one came to love, because he was principled. I remember coming into his office one day and he was reading The Nation. I had subscribed to The Nation for years, and I asked if he subscribed. He said, "No, I don't, but I do think we should know the other fellow's point of view."

Harold Prince (She Loves Me, which he also wound up producing, as he did Fiddler): In 1962, we had seen A Family Affair before Hal had been called in to try and fix it, and after Hal had tried. [It was the first Broadway directorial credit for Prince, who had become famous as a producer.] It had had severe problems, and Hal damned near fixed them. Jerry Bock and I knew that Hal had much more going for him than just producer skills. When we were doing She Loves Me, we were talking about directors. The first one suggested was Gower Champion, and Jerry and I said sure. But it turned out Gower had prior commitments. And we said, how about Hal Prince? So Hal was approached, and he was delighted. And I think a day or two after Hal was approached, Gower called and said, "I no longer have those commitments." And Jerry and I said, "No, we can't do this. We offered it to Hal, let it be Hal." And we were so glad we did. (Hal became our co-producer later.) Because what Hal brought to rehearsals was an enthusiasm and an exuberance and a sense of humor and a sense of theatre and a mastery of what he was doing. It was not a surprise, but it was a wonderful confirmation of what we expected from him.

|

||

| Joe Raposo |

ON WRITING BOTH MUSIC AND LYRICS, as he did at first and has done recently: All the years I was working with Jerry Bock, I always wrote with a tune in mind. It's not that I'm looking for it, it's just there. It may not even be a fully formed tune, it may be kind of fragmentary, but there's something in my mind. At a certain point working with Jerry I had to forbid those tunes from entering my mind, because otherwise, when I gave a lyric to Jerry, if I saw it as a waltz, and he saw it as an up-tempo, it was very difficult to hear what he wrote through the filter of what I thought it should be. So I had to be very careful not to get very attached to the tunes that came into my head.

|

||

| Jerry Bock |

||

| photo by Aubrey Reuben |

THE NO. 1 RULE: When you're writing lyrics, it's not like a poem on the printed page. With a poem, take Emily Dickinson, a four-line poem may be so dense that you have to read it four or five times before the meaning opens up to you. With a lyric, you have an audience that's listening, and they're hearing new music, and there are other elements — lighting, costumes, performers. So the audience has to grab that lyric the first time they hear it. The trick is to be both fresh in the language but also immediately comprehensible, because otherwise they're going to turn off.

I remember a lyricist, who shall remain nameless. He invited me to see one of his shows in previews. I called him afterward and said, "Well, you do something that disturbs me — you're using these three- and four-syllable rhymes, and you use them so much that it constantly calls attention to you, and I keep forgetting the context. All I think is that this is the writer showing off, which I don't think is good." Long pause, and then he said, "Well, most of my other friends tell me they're very impressed by my virtuosity." And I thought, "OK, that's what you want to do — do it."

|

||

| Montego Glover and Chad Kimball in Memphis |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

Ragtime, especially in this last revival, which I thought was magnificent.

THE QUALITY OF TODAY'S MUSICALS: I'm kind of worried, because I go see a show like American Idiot, and on several levels, I found it very off-putting. One was just the sheer volume. I sat there with my fingers in my ears, and I thought, that's not the way to watch a musical. Also, the book seemed to be relatively unimportant. What seemed to be important was the rock-concert element of it. I felt the same when I saw Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson on Broadway. And I thought that for my taste, this is lowering the bar. It's campy. It's not my idea of theatre. What worried me was not the shows but the critical reaction to them, because both garnered rave reviews, and for my taste they don't deserve rave reviews. I don't know whether this is the harbinger of the future. I know that shows with contemporary music can work for me. Rent, for example. I thought it had wonderful songs.

With Next to Normal, the volume was such I could sit in the theatre, and I thought the songwriting range of Tom Kitt and Brian Yorkey is wonderful. It's not just a rock show, it touches all the bases. So it's possible to do that kind of show.

|

||

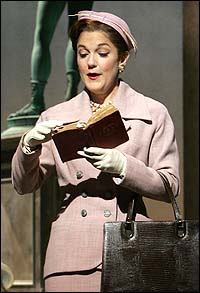

| Victoria Clark in The Light in the Piazza. |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

*

As previously reported on Playbill.com, a concert reading of Harnick's new musical, A Doctor in Spite of Himself, based on the Moliere play, will open the 30th Annual William Inge Theatre Festival, which runs from April 13-16 in Independence, Kansas. He wrote music, book and lyrics.

Read the recent Diva Talk column in which Kate Baldwin talks about her Harnick tribute show at Feinstein's at Loews Regency.