*

Porgy and Bess [RCA Red Seal/Sony 88697591762]

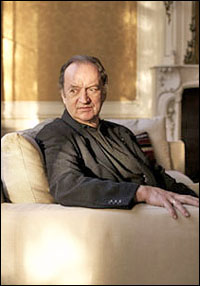

"This is world music of universal relevance," says the sticker affixed to conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt's new three-CD recording of George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess. The listener carefully perusing said sticker is likely to become suspicious, though, when he or she notes that the "universal relevance" quote which the manufacturers have seen fit to use comes from Nikolaus Harnoncourt.

That doesn't mean, however, that Mr. Harnoncourt is wrong. Broadway types and readers of this column might not know the name; the 80-year-old Harnoncourt is an Austrian conductor specializing in Bach and music of the Baroque period, who prior to tackling Porgy had probably never set foot anywhere near 20th century American music. Harnoncourt is royalty, actually: Count Nikolaus de la Fontaine und d'Harnoncourt-Unverzagt, a direct descendant from Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor (circa 1790), King of Hungary and Grand Duke of Tuscany. And brother of Marie Antoinette, as it happens. All of this doesn't matter a jot to you or me; but George, a poor boy who grew up playing stickball on the streets of New York, delighted in hobnobbing with bluebloods. A great great great grandson of Leopold II championing his music and giving the world an exciting new recording of Porgy and Bess? George would probably be tickled.

Any number of conductors have come along claiming that they have put back the pieces of Porgy in the one and only form that George himself intended, and Harnoncourt is simply the latest of them. To paraphrase Bernard Shaw, though, by George I think he's more or less got it — or a fair approximation. One needs to step back a moment, though, for a brief explanation of the tangled state of Gershwin's score. Porgy people could write a book about it; one of them, Wayne Shirley (formerly of the Music Division of the Library of Congress), seems to be doing just that, and I expect it will be worth the wait.

George finished his complete Porgy and Bess, orchestration and all, in August 1935. (The full scores, in George's ultra-artistic handwriting, are in themselves a work of art; like a medieval monk's Book of Hours, they are breathtakingly inspiring to view.) When the opera composer writes "the end" — or more specifically, "fine" — that marks his final thoughts on the subject. When a theatre composer writes "the end," though, it is only the beginning. As a show is cast and rehearsed and run-through and previewed, change after change comes into the score. Musicologists and academics all too often insist that the original score is sacrosant; changes that came in at the behest of a philistinical producer or director should be undone and removed so we can get back to the composer's true vision. This is, in most cases, utter nonsense, in theatrical terms; any heir or estate or lawyer that thinks otherwise is doing a grave disservice to the work they are supposed to be protecting. Theatrical shows — and Porgy and Bess was very much a theatrical show — are by nature rewritten and improved (hopefully) up until and sometimes past opening night. And that's the way Gershwin worked on all his projects throughout his career.

|

||

| George Gershwin in 1937 |

||

| photo by Library of Congress |

Porgy and Bess was not so much rewritten as cut and trimmed, in rehearsal and during the Boston tryout. Did Gershwin agree with all of the changes? Probably, as he was a practical man of the theatre (and likely to be insistent when he felt the need to be). Were there items that he agreed to cut despite believing that they were essential? Yes, in at least one case that we know of. That's the famous "Buzzard Song," which comes along at a critical juncture, changes the tone of the piece, and thrusts the action forward. It is a difficult song to sing, though — especially if you are singing the rest of the role of Porgy as well — and it turned out to be one song too many for Todd Duncan, the actor who brilliantly created the role. (Duncan sang eight shows a week; tell that to subsequent Porgys and Besses who regularly split the chores with alternates.) "The Buzzard Song" was regretfully cut, but it remains a key part of the score and one which present-day, two-or-three-performance-a-week Porgys can and should sing. The rest of the changes made prior to the New York opening? Surely George was agreeable to seeing most of them go. The only reason we can have this discussion, by the way, is because George's publishers saw fit to publish the vocal score of the original, pre-Broadway version — including the material which was cut and never performed during composer's lifetime.

Porgy and Bess came to town on Oct. 10, 1935 and departed after 124 performances; it was a hard sell, and it was the depths of the Depression. Gershwin died in 1937, and was understandably lionized. In 1942, producer Cheryl Crawford was running a summer theatre in Maplewood, NJ. War rationing forced the closing of the place, so she decided to go out with a bang and gathered as much of the original cast as possible and produced — for a week — a grand Porgy and Bess. A canny theatre person — co-founder of The Group Theatre and The Actors' Studio, producer of such items as One Touch of Venus, Brigadoon and Sweet Bird of Youth — Crawford had loved the original production but thought the show was harmed by the many operatic recitatives. They seemed stilted, she thought, coming from these characters in this setting. (Crawford singled out the line "Oh, Gawd, don' let 'em take Bess to the hospital" as a for-instance; sounds silly being sung, doesn't it?) So she cut out many of the recitatives, streamlining the piece. Alexander Smallens, the original conductor, was there with her, wielding the pencil at her direction. (DuBose Heyward, who wrote the libretto and most of the lyrics, died in 1940.)

Crawford's summer stock Porgy and Bess revealed the richness and vibrancy of a show that had been seen as something of a noble failure only seven years before. Investors clamored, with Lee Shubert inviting Crawford to bring her cut-down Porgy to the Majestic. The show was an immediate hit in a way that the original had not been, running 286 performances and successfully touring (including two return NYC engagements within a two-year period). This spawned further tours, including a well-received international company in the 1950s which enjoyed a 305-performance stint at the Ziegfeld.

|

Harnoncourt has made informed decisions of what material George would have chosen to keep out, and what he would have been sure to reinstate (like the aforementioned "Buzzard Song"). So what we get here is not the Porgy of the published-in-advance vocal score; not the Porgy of the Boston tryout or the original Broadway engagement; not Crawford's streamlined and highly successful Porgy, or the opera house restoration or Mauceri's reconstruction of the 1935 show. Here we have yet another version. Without doing an extensive comparison of the varied versions, Harnoncourt seems to have come up with a pretty good one.

|

||

| Nikolaus Harnoncourt |

||

| photo by Marco Borggreve |

All in all, Harnoncourt has given us an exceptionally strong Porgy and Bess. Musically, that is. Which makes this album — recorded live at the Styriarte Festival in Graz, Austria in the summer of 2009 — one to listen to, and perhaps remain on the shelf beside the old Decca recording made by members of the original cast (at sessions in 1940 and 1942). There is a problem with this Porgy and Bess, though, in the matter of the Porgy and the Bess. Jonathan Lemalu might well be a fine opera singer, but he doesn't seem comfortable in the language. A native of New Zealand, he speaks English; just not Catfish Row English. That being the case, little emotion seems to get across from this Porgy. (Duncan's recordings are almost 70 years old, but he is at every moment convincing — as are William Warfield and Lawrence Winters on other recordings.)

As for Bess, she is missing in action. Isabelle Kabatu sings like an opera singer, rather than an actress, and at times is altogether indiscernible. Gregg Baker, the Crown, is the only standout in the cast, with some good contributions from singers in some of the smaller roles. The lack of a Porgy and a Bess might seem fatal to a recording of Porgy and Bess. Not so; Harnoncourt does such a good job, and his orchestra plays so well that they make up for the lapses of the leads. (Steven Suskin is author of the recently released updated and expanded Fourth Edition of "Show Tunes" as well as "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," "Second Act Trouble" and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He can be reached at [email protected].)

*

Visit PlaybillStore.com to view theatre-related recordings for sale.