*

You've read, no doubt, that composers Andrew Lloyd Webber and Alan Menken have three shows each currently playing on Broadway. But so does Tony, Grammy, Golden Globe and Oscar-winning lyricist Tim Rice — with the revivals of Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita, plus the long-running The Lion King.

Whether you performed in a high school production of Joseph and Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat or took the grandchildren to see the 3D re-release of "The Lion King" last summer, you know the work of English-born Rice. In the 1990s, the Disney animated films "The Lion King" and "Aladdin" catapulted the lyrics of "A Whole New World," "Hakuna Matata" and "Can You Feel the Love Tonight?" to worldwide fame. The film work led Rice back to Broadway — where his Joseph, Jesus Christ Superstar, Chess and Evita songs had already been popular in the 1970s and '80s. In the '90s, his work was heard in the Broadway stage musicals Beauty and the Beast, The Lion King, King David and Aida.

Rice talked to Playbill.com by phone from England in recent days. He spoke candidly about his long career, his new musical version of From Here to Eternity, using religious texts as source material and a solution to the popular and problematic Chess.

Your projects have often used the same source material — The Bible. Superstar is currently running alongside a myriad of other spiritually driven musicals on Broadway. Why are these themes so popular in musical theatre?

Tim Rice: I suppose, it's a very important part of everybody's life. And one can write about religion without necessarily following it. Sister Act, for example is a comedy. It's a very enjoyable show, but I wouldn't have said it was particularly reliant on people understanding the Christian faith. None of these shows are setting out to preach any sort of message. They're primarily telling a story. Superstar, for all its faults or naïveté is really trying to tell a story of how somebody such as Judas Iscariot or even Pontius Pilate or Herod would've reacted to somebody saying he was God. Or at least having other people claim he was God. You've come back to that well as recently as last year for the Bush Theatre's Sixty-Six Books in the U.K. Was that pure coincidence?

TR: With the Bush project, I was asked, along with 65 other people, "Would I be interested in writing a poem or something about one particular book of the Bible?" I really didn't know which book I was going to get. I enjoyed doing it because I think the Bible is a source of great stories. And I got Chronicles II, which is a book I didn't know very well. Although I did discover it contained the story of Solomon and Sheba and ended up with Cyrus the Great of Persia being kind to displaced Jews, which I thought was a lesson for today.

But I didn't go back to that particularly. I agreed to do it because I thought the Bible's bound to have a good story, but it wasn't something I thought, "My God, I must get back to do the Bible." It just happened they rang me up. But I do think the Bible is a fascinating, endless source of stories and I always enjoy dipping into it and reading the odd chapter that I haven't read before.

| |

|

|

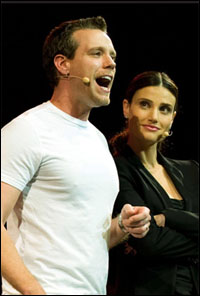

| Josh Young and Paul Nolan in Jesus Christ Superstar. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

TR: Absolutely. I had always wanted to do King Saul. I thought that was a fascinating story. In a way, it's what we did with King David many years later.

Why the shift from Saul to David?

TR: King David was a commission. Michael Eisner of Disney was approached, I believe I'm right in saying, by an Israeli entrepreneur who was keen to have King David as a piece commissioned for the 3,000th anniversary of Jerusalem. Alan Menken and I had discussed King Saul, because that had always been one of my ideas that had been bugging me. When we heard about this idea to do King David's story, we thought "well that's great," because King Saul is very much at least the first half of David's story. So we jumped at the chance. And I feel, in a way, with King David — which hasn't really been done much apart from being on in a concert at the New Amsterdam Theatre in New York — we've almost written two musicals: Part One is the story of David and Saul — and that's the musical that really intrigues me — and Part Two is the story of David, Absalom and him coming to terms with death and looking back on his life.

We do intend to go back to King David, and maybe just look at the first half and do a normal-length musical rather than an incredibly long sob-opera. It's a fantastic story, in the way that Saul, in particular, feels he was misled by God and indeed by Samuel, the Prophet, who claimed to be the representative of God. And it's a tragic story of a gifted man who was completely upstaged by an even more gifted man.

We're having a kind of Tim Rice/Andrew Lloyd Webber retrospective on Broadway right now.

TR: Just what you need.

In seeing these revivals of Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita, were there moments when you said, "I can do better than that"? Or, "I was pretty smart for a young writer"?

TR: My son who's just starting out in the film world — he's got a movie coming out in the Tribeca Film Festival — made a very good point. He said, "You've got to make the most of your inexperience because you won't have it for long." And in a funny way I think that's what we did with Superstar. We didn't quite know what we were doing and consequently we didn't feel there were any rules we had to obey. When I saw Superstar last week, I thought alternately "Oh, that is a great line," and then, "My God, that's awful." [Laughs.] Though I think — more than most shows — Superstar doesn't really benefit from a close line-by-line analysis. I think some of the lines stand up to it, but I think it's sort of an inexperienced explosion of ideas and enthusiasm. And if you take it at that, it works. If you start saying, "What is this compared to Stephen Sondheim?" It doesn't compare to Stephen Sondheim. It's almost a totally different animal.

With Evita, it's in some respects much more conventional. There are very few lines in Evita I would change. There are quite a few I would change in Superstar. That doesn't mean to say one is a better show than the other, it just means it's in a different stage of one's career. If I were writing Superstar now, it would be totally different. And it probably wouldn't be as good, even though the lines would be more sophisticated.

Read about the Broadway career of Tim Rice in the Paybill Vault.

| |

|

|

| Josh Young as Judas | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

TR: It now might seem a bit old hat, but 40 years ago Jesus Christ Superstar, the very title, people would go "Oh my goodness, what's that about?"

Unintentionally, we were ahead of the game really; and all we were trying to do was tell a good story. It happened to be a Bible story, but we were trying to tell a famous story in a new way. And it was a story that most people already knew and had views about. But in its day — 1969/1970 — it was quite a groundbreaker.

I think you've got "clever" critics now, who weren't even born when Superstar came out. who say, "Oh, well, this is all old-hat." But my answer to them is "What were you doing in 1969? F**k all." [Laughs.]

For all its naiveté, it has great excitement and it's very direct. Some people have said, "The apostles have rather simple lines." Well they were meant to because they were simple men. I felt at the time, and now, that I couldn't give the apostles incredibly sophisticated choral lines because a.) it wasn't justified by what they said in the gospels. And b.) they were uneducated men. The odd, educated one, such as I made Judas, was somebody who could actually see beyond the crowd mentality. But the other lot were quite happy, as they are in the Gospels, to sing "Hosanna" or "I wanna be an apostle." They were meant to be that simple, and arguments between Judas and Jesus went above their heads.

Do you think criticism of "Judas" stems from audiences wanting to relate to the hero of a story, and when they realize they actually relate more to the anti-hero they become uncomfortable?

TR: I certainly would identify more with Judas than with Jesus. Anybody who identifies with Jesus would probably get locked up. If somebody went 'round the streets today and said, "I am Jesus," he might get a bit of a following, but basically he would be regarded as somebody a bit strange. Whereas somebody questioning culture and religion, whatever culture or religion you're questioning, is usually regarded as someone who is quite intellectual. You've often managed to shine an empathetic light on some unlikely characters — Judas, Pontius Pilate, Eva Peron, even Freddy in Chess. Is this something done consciously or is it a by-product of the material?

TR: I think probably a by-product of the material. But I must be, initially, attracted to these characters. Again, it's easier and more natural to identify with a character who is flawed than a character who is all but perfect. So I think I enjoy writing about these imperfect people because it seems to me that I'm quite like them.

| |

|

|

| Adam Pascal and Idina Menzel in the 2008 Chess concert. |

TR: Oh yes. I enjoyed doing that.

The story, in that version, seems extremely satisfying. Did that event spark an official revision?

TR: If I were to ever stage it on Broadway or anywhere, I would basically do this version — I thought it worked jolly well.

I think the problem that Chess has — and it sounds stupid — [is that] you can't hear the words. It's a complex show. So if it was spoken and there was no music, you might not think the words were any good, but you'd understand the storyline. The perceived wisdom is that it's got a great score, nice songs but the story is rubbish. Well, I would say the story is not rubbish. It's complicated. And if you miss great chunks of it because you can't hear it, then that's a problem.

With a show like Superstar, where everyone knows the story, or even a show like Evita or Phantom where the story is pretty straightforward — not incredibly complex — then it doesn't matter if you don't hear every word. There's a song in Chess called "Merano," which is a Tyrolean spoof. And it's always played with total bewilderment from audiences — because they can't hear a word. Cameron Mackintosh said to me, "Well you've got to get rid of that Tyrolean stuff at the beginning. What's that all about?" And the answer is, it's actually quite funny and it makes a point.

So when we did the Albert Hall, we used subtitles and for the first time ever it got big laughs and a round of applause because people enjoyed it. And I always feel that if ever I did Chess on stage, I would have subtitles. I would have every word clear.

Read about the Broadway career of Tim Rice in the Paybill Vault.

| |

|

|

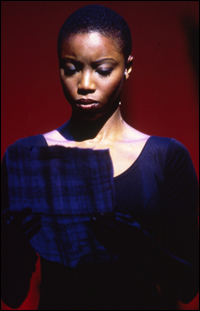

| Heather Headley in Aida. | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

TR: I suppose, firstly, there was nothing in the last ten years — there was no great idea — that really grabbed me and thought I must do this! —except, funny enough, an idea I've had and am also working on…about Machiavelli. But a young friend of mine called Stuart Brayson, who's a very talented musician, came up with From Here to Eternity. He was sending me about three musicals a year. He lives some way away from me in the north of England and every so often he'd send me a CD and I'd listen to it, cause I knew he was good. And occasionally I'd say, "Well, this one's got potential" and I would send it to a producer or something. But nothing else ever happened. Then he sent me From Here to Eternity. He'd written a musical on that and I said to him, "Have you got the rights?" And he said, "Rights?" And I said, "You can't just do it without them, which is a pity because this is actually rather good and it's a great story and you've written some wonderful songs." So I told him I'd get the rights and by the time I'd taken two or three years getting them I was sort of on board as a producer. I then hocked it around London a bit, and a producer called Lee Menzies was very interested. So Lee and I put together a team, and then it was decided — and Stuart himself was also very keen — that the words should be re-done. So I then ended up not only being a producer, but I was also a lyricist, and it was turning into quite a good show. So we made some demos and put it all together. Now we're ready to rock, we're just looking for a theatre.

I must admit, I'm really only familiar with the film. Does the film represent the novel pretty well?

TR: I think it does. The novel is a huge tome and it's a terrific book. The more one reads it, the more you think well this is actually, beyond any doubt, one of the greatest American novels of the 20th century. There's an awful lot in it which the film, simply by virtue of time, can't deal with — as the same will be true for us. But if you want to get a quick handle on the story, the film is a pretty accurate reflection of that.

| |

|

|

| Samuel E. Wright in Broadway's The Lion King. |

TR: It's interesting. I was very glad to have the lucky break of working with Disney in the '90s. But it was just nice to do what I thought I could do reasonably well, and yet do it in a new medium. Ironically, Disney got me back in to the theatre, because they suddenly began saying, "This stuff is quite good. We should do it on Broadway" — first with Beauty and the Beast and then The Lion King. Then we wrote one without a film beforehand, Aida. Finally I thought, "Blimey, I'm back in the theatre thanks to Disney." But I've always kind of had an attitude of 'I like to write songs and I don't really mind in what format I do it.' And From Here to Eternity was through a friend of mine, so it was an unlikely source.

How would you categorize the sound of From Here to Eternity?

TR: I'd like to think it's recognizable as contemporary music. I would like to think a lot of the music couldn't really have been written that long ago. But having said that, it's very tuneful and a lot of it's very traditional and you would think this is a traditional score.

I'm going to call you a "Founding Father" of the rock musical.

TR: [Laughs.] What a man you are. I've always admired your writing! As you watch the next generation of writers, are there shows that have you saying, "That's a voice I'm proud to say carries the rock banner forward?"

TR: It's sound awfully ghastly to say but I haven't really — no. They're been an awful lot of people writing musicals in a much more traditional format. There have been some interesting things I've seen over the years, but I've always been banging on about the fact that in Britain, certainly, there's nobody really emerged permanently since Andrew and I. There's a very good team called Stiles & Drewe who've had considerable success in England, but they're much more traditional theatre people — and very good they are. But the people who've had hit musicals in remotely contemporary areas have all been old codgers like Elton or us. The guys at the top of the game seem to be our generation, which is a bit worrying really. I haven't yet seen Matilda, which I must go and see and which has done very well here. So I must exclude that from any criticism.

Read about the Broadway career of Tim Rice in the Paybill Vault.