*

Christine Jones was Tony Award-nominated for her work on the Broadway musical Spring Awakening, a Michael Mayer-directed musical about troubled young people. It was set in a simple, multipurpose, open space with some platforms and furniture for punctuation. Collaborating again with Mayer in 2009 — on American Idiot, the Green Day musical about troubled young people — she created a second open space onto which the director could splash his vision. She took home the 2010 Tony for Best Scenic Design of a Musical. Jones answered our questions about imagining new worlds on stage.

There is jolted-heartbeat energy to American Idiot, a kind of emotional chaos, and it's evident in the collage-like quality of your scenic design. Did you know early on in discussions that the major "pattern" on the back wall of the set would be controlled chaos of posters and media clippings?

Christine Jones: Yes, some of the first images I looked at were of punk clubs, like CBGB's and Gilman Street, where Green Day got its start. I immediately responded to the layers of posters and decals that plastered the walls. I wanted the space to feel like many locations simultaneously: rock club, live/work art studio, teenage slacker's bedroom — the posters helped the set ride all of these places....

Can you talk about what's on the back wall?

CJ: I hired a recent student of mine, Damon Pelletier, to work on collecting all of the different posters. Being a kind of rock slacker himself, in addition to a great designer, I figured he'd have just the right sensibility. He pulled images from clubs as well as from a range of international street artists. There was hardly anything we didn't use. We used the term Maximalism while we were working on the show. In concert, [Green Day's] Billie Joe [Armstrong] says he is out to give the fans the best rock show they've ever seen. Watching the actors bust their hearts out in rehearsals also inspired me to keep adding layers — like there could never be too much detail... I invited everyone: actors, carpenters, painters, props people, to put up their own photos, write on the walls... The set started as a structure made of wood and metal, but by encouraging everyone to leave their mark, I hoped to give it a heart.

What's the oddest thing on the back wall that makes you smile, even if it's not evident to the audience?

CJ: There are so many things on the back wall that the audience can't see. One of my favorites is a BB gun with a piece of brown paper taped next to it on the wall to keep score of how many rats have been killed. Billie Joe told me about one of the first spaces he lived in that was a big empty warehouse. He had a mattress, a garbage bag full of clothes and a guitar. He and the guys he lived with would shoot at the rats to keep them at bay and keep score as to who was winning: US or THEM. My kids' drawings are there too. They make me smile the most.

| |

|

|

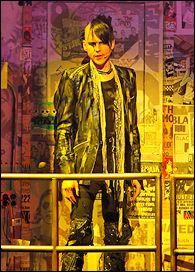

| Tony Vincent in American Idiot | ||

| photo by Paul Kolnik |

CJ: Only in relation to Jesus of Suburbia, during which a shopping cart full of "trash" is brought in and strewn about the stage. That image began as an idea about media pollution and 7-11 junk food saturation that gets used to "trash" the stage. I'd say it was used more as a verb than as a noun.

What "clues" from the Green Day score/album did you pick up on or respond to when addressing the design?

CJ: I listened to the music voraciously. I felt a call to action to make sure the environment, and the potential contained within, could match the energy and pulse of the music.

When you won the Tony Award, you called Michael Mayer a genius. Can you give us a sense of what it's like to be a creative partner with him?

CJ: It's like falling in love. There are sparks flying, fun work dates and delicious meals. Each of us brings our best to the table, and I'm excited every time we get to be in the room together.

What about him makes him a genius?

CJ: I referred to him as the Jesus and the Judy of Broadway, making reference to both American Idiot and Everyday Rapture, which we also worked on together. Everyday Rapture was remounted at the last minute during the last week of previews of American Idiot. Michael would be at the St. James, spinning the Jesus of Suburbia and his gang into a frenzy, and then would run over to Rapture and help shape Sherie Rene Scott's musings as to whether to chose the words of Judy [Garland] or Jesus.

Michael can hold his own in a mosh pit, as well as sing every show tune that has ever been sung. He is always one step ahead of everyone, and is one of the smartest people I have ever met. His ability to keep a thousand details crystal clear in the fingertips of his brain is staggering. Add to his mental dexterity that he's the first to cry when a moment lands, and you have before you a man with a gorgeous combination of vision and heart.

I've told Michael that that show is a living work of art — that it's a little like stepping into a dream. It does not want to be literal, and then when it is — it hits you. There's a serious tension to the design, if I am putting that right. Or am I articulating that badly?

CJ: No, that was the goal. It was intended to be many spaces simultaneously or exactly where you needed it to be when you wanted to be somewhere, whether in Johnny's bedroom, on the highway, walking the streets of New York, or in the trenches of Iraq. Lights, video, projection and clothes, more than you know, conspired to take you from one to another.

You've talked about early discussions with Michael and your fellow designers being brainstorming sessions. What did you all know had to be part of the world from the first discussions?

CJ: We knew that the combined elements had to create an energy that matched the excitement of a rock show. We knew the music had to be a part of the world, that the band would be in the center of the event on stage amidst the action taking place.

Was there an idea that was discovered late — that is, something you learned at the tryout at Berkeley Rep in fall 2009?

CJ: Knowing that we were trying to assimilate the energy of a rock show, we experimented with ideas that came from the Green Day concert lexicon: specifically…t-shirt guns. We got the idea of shooting t-shirts into the audience while we were at Berkeley, and then had the band's wizard make a double barrel gun for us, which we tried once we got to the St. James. We discovered, that while we were playing with rock show elements, our show's roots needed to stay planted in the narrative, and in our connection with the characters — if we did anything that was just for the sake of cool or fun, it didn't work.

Was video — imbedded screens — always expected to be an element in the scenic design? How many screens are up there?

CJ: Early on we had the idea to cover the walls with TV screens and use them sculpturally as well as imagistically, but we were also clear that the world had to have its own integrity without video or projection. The presence of the TVs was there from the get-go, but what would be on them evolved as another layer. There are 43 screens in the walls and in the stacks.

Darrel Maloney's video and projection design is very much a part of the visual world of American Idiot. From a practical standpoint, does your work have to have certain color neutrality to accommodate projections? Or can projections and light blast through anything these days?

CJ: The power of the new equipment is astonishing, but we did mute all of the posters into tones of greys, so that they would be more receptive to the projections.

| |

|

|

| Stark Sands, John Gallagher Jr. and Michael Esper | ||

| photo by Paul Kolnik |

Having worked with Michael on Spring Awakening, did you feel a responsibility to be visually different somehow for American Idiot? Did you think, "Let's not make this choice because it echoes our earlier piece"? An example?

CJ: I'd say we went into the process with a blank slate and that the inherent qualities of Idiot made the work feel unique from Spring Awakening, but we did add a turntable to the platform that rises out of the ground during the shooting-up scene of "Last Night on Earth," after Charles Isherwood made the observation that it resembled the hayloft in Spring Awakening. The comparison inspired us to push it a step further.

You have designed many different kinds of productions. Is there a favorite sort of world you like to create? That is, if a director is seeking a very traditional, literal living room setting, does it make you somewhat — itchy or frustrated?

CJ: When I graduated from NYU, I thought that I never wanted to do a kitchen or living room set, but working with James Houghton on Last of the Thorntons and Burn This allowed me to find the joy in recreating more conventional spaces. While working on the Thorntons we went to Wharton, TX, and spent a weekend with Horton Foote, and then while working on Burn This, I haunted the living spaces of choreographers. I discovered that the forensic process of discovering in what kind of space a show will happen in is wonderfully similar whether the space is literal or not. You are always looking for clues — in the music, in the text, in the behavior of the characters — and putting them together to make a three-dimensional picture.

Where did you grow up?

CJ: Montreal, Quebec.

Did you go to theatre as a kid, were you exposed to art and theatre?

CJ: I don't recall going to the theatre, but I saw the film "The Turning Point" when I was ten, came home and sat on the washing machine crying for an hour, telling my mom that I would die if I could not be a dancer. I spent several years studying with Les Grands Ballet Canadiens, until I was in the Nutcracker and saw more close up how constricting the professional world of dance could be. I wasn't ready at 15 to make that singular commitment, despite my ten-year-old self's yearnings. How did you get interested in designing for the stage? Inspired by an early performance experience?

CJ: I left dance behind to study theatre, and while doing so was guided by a teacher who suggested I might want to pursue "scenography." I thought he said "stenography" and had no idea what he was talking about. He told me what a scenographer did, and a light turned on. I went on to study at Concordia University and while there saw a production by a group called Carbon 14, titled Le Dortoir. It was my second epiphany, and I sat in the theatre crying at the end of the show, knowing that was the kind of work I wanted it do. It was a perfect blend of theatre and dance. It was dangerous, electric and gorgeous. I feel American Idiot was the direction I was headed in from that moment on — it's the closest I've come to being able to make a world that gets eaten alive by the performers.

Is there a theatre designer who influenced you or inspired you?

CJ: The look of my work is probably more inspired by photographers and installation artists, but I would like to think that the manner in which I try to do the work is inspired by people like John Conklin and Tony Walton. They are passionate about what they do, and never cease being curious. They are Theatre Animals of the first order.

You teach design for stage and film at NYU's Tisch School. What's the one thing that you keep reminding design students — perhaps something they are slow to learn?

CJ: That we work on PLAYS. It should be fun, and one of a designer's best traits is their ability to play well with others.

What is the most important thing for a young designer to know?

CJ: How to do "The Hokey Pokey" —"you put your whole self in."

Are you and Michael Mayer going to work together again soon?

CJ: Yes. We will be doing The Illusion by Tony Kushner at the Signature Theatre in the spring.

What else is coming up?

CJ: So far, The Illusion is the only new project I have committed to. I am the artistic director of Theatre for One, and am trying to carve out more time to devote to its development. In addition to teaching, I am mom to Pilot, 5, and Ever, 3. I consider myself a part-time designer, and try to make sure I spend more time with my kids than I do working.

(Kenneth Jones is managing editor of Playbill.com. Write him at [email protected].)

To see more of Jones' Tony-winning design, watch highlights from American Idiot:

Evan-Zimmerman-for-MurphyMade.jpg)