*

Arena Stage's artistic director Molly Smith has been in the spotlight so much recently — for the fall opening of Arena's new $135 million home at the Mead Center for the American Theater, and for her acclaimed new Arena production of Oklahoma! — that you might easily mistake the charismatic leader as The Artistic Director of All American Regional Theatre. Now more than ever, Washington, DC's Arena Stage — founded in 1950, when "regional theatre" wasn't yet a widely used term — appears to be the true flagship of American resident theatre. The company's massive new facility is the most obvious (and latest) evidence that Smith has sought to grow the organization. Her imagination became evident the moment she began at Arena in 1998, when she boldly changed the programming mission from producing eclectic plays and musicals by international and U.S. dramatists to mounting strictly American fare. At the time, she said, "Why do we go to Washington? To learn what the American mind is: the ideas, drives and passions that make us American." She has stretched the organization (and stretched her own muscles as an artist and an administator) in the past 13 years. She's more passionate than ever about making Arena exactly what it's billed as on the new front door: the "center" of American theatre. That means producing world premieres and second- and third-stagings of works that might not have had a fair shake the first time at other theatres; putting playwrights on salary; presenting creative revivals like the multicultural Oklahoma!; and inviting great U.S. regional companies (like Steppenwolf, due next spring) to play at Arena.

But, who is Molly Smith? In the weeks after the October launch of the Mead Center, we asked the 58-year-old leader who she thinks she is.

I think of you as the busiest artistic director in America. Is it easing up for you a little bit?

Molly Smith: [Laughs.] Well, you know, I took a few days to relax and went to the desert and rode a horse and walked through the desert and thought about my life, and that was fantastic.

We haven't really talked about your personal background and what makes you tick as an artist. I don't know where you grew up and what your first brush with theatre was —

MS: I was just speaking to our interns and fellows a little bit about that today. I was born in Yakima, Washington, which is a town not known for its theatre, and from the time I was a little kid, I was really interested in the theatre. [I] was not a particularly good student in grade school, but my mother told me after one of her meetings with the sisters — I was at Catholic school — she sat down with me at the kitchen table and she said to me, "Molly, at some point you are going to find something that you love, and you are going to be incredible at it." And I've always appreciated my mother for that, because really, the only thing I was interested in was literature and theatre, from the time I was very young. What kind of theatre were you exposed to at Catholic school?

MS: At Catholic school, it had more to do with readings from the Bible, little short plays, and then I worked early on in teen theatre in Yakima, Washington. Then, when my family moved to Alaska — my father died a few months before I was born, and my mother took my sister, Bridget, and I to Alaska, when I was 16. I was there for about 25 years. And in Alaska, I was in high school playing Titania in Midsummer Night's Dream. And then I was at The University of Alaska when I was 19 years old. I had been in a pre-law degree, and a friend of mine and I traveled to Europe for three months with a backpack during the Vietnam War, and I made the decision, while we were traveling, that I wanted to go home to Alaska and start a theatre company.

Resident theatre was sort of unheard of in Alaska at the time, wasn't it?

MS: Yes, it was. I knew about theatres that were happening around the United States, but there wasn't any resident theatre in Alaska. There were a few community theatres, and there were a few small opera companies at that time. So I went back to the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, which gets to be about 60 below zero during the winter, and went in to tell the chair of the theatre department my plan, that I was going to start a theatre in Alaska. And he patted me on the shoulder and said, "That's very nice, dear." And a couple of months later, I left The University of Alaska and then ended up at Catholic University here in Washington, DC, because I figured if I was going to start a theatre in Alaska, I needed to learn everything I could about theatre [and] I knew I would need to teach.

And Catholic U has one of the great theatre programs in the country.

MS: Yep. And that was where I met Paula Vogel. We were both transfer students, and I went on from Catholic University [after earning a bachelor's degree in theatre] to American University — that's where I got my master's degree and [I] met [director and DC Studio Theatre founder] Joy Zinoman there. But where I really learned about theatre is by going out to all the small theatres — New Playwrights' Theatre, The West End Theatre, Back Alley Theatre, Washington Area Feminist Theatre, and I would ask them, "How can I learn about box office? I'll be your box-office person." Or, "I'd like to learn how to stage manage. Will you teach me how to stage manage?" Or, "How do I read a new play?" And so, that was my internship in the theatre.

|

| Smith and managing director Edgar Dobie welcome the audience at the Opening Gala Celebration for Arena Stage at the Mead Center |

| photo by Scott Suchman |

| |

|

|

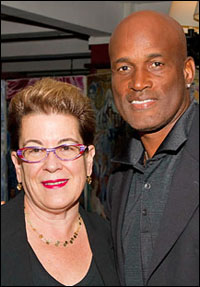

| Smith with Kenny Leon |

MS: I was an actor, and it was when I was at American University that I realized that every time I was acting, I kept going out into the house to watch what the other actors were doing, and I kept sitting further and further back in the house, and I had thoughts about the way in which they should be performing their roles. So that told me — when I was about 25 years old, the last role that I did — that really told me that I was really moving quite quickly into being a director. And I think, as an actor, I was limited. Mostly, my range was narrow. I was mostly interested in being just about who I am [laughs], which is not good for an actor but is very good for a director. I was not a chameleon.

You were on an acting track, but inside of you, you knew that you wanted to run a theatre or open a theatre, correct?

MS: Yes, I knew I wanted to open a theatre. So I was 19 when I made that decision. I don't think I knew how I would do that, but I had this idea in my head that I wanted to do it. That's why I ended up on the East Coast, going to school here, because I knew I'd get the training I needed to start this theatre in Alaska. My friends, of course, thought I was completely crazy.

By the time I was 21, I started directing. I was directing and I was acting and I was stage managing concurrently, so on some productions, I'd be doing one or the other or the other, but really, by the time I started directing, my focus pretty quickly was turning toward that.

And why Alaska? I know you grew up there, but why did you say, "I want to go back there and form a theatre?"

MS: Because I knew people would say yes to me, and because there wasn't any [professional theatre there]. Here I was in Washington, DC. It was very rare that a woman would be given a role as a director here. My first professional job was with the Washington Area Feminist Theatre. It was very difficult to convince any theatre that, as a woman, I would be a good director. And so that was something that was also clear to me, that in order to do the kind of work that I wanted to do, I would have to start my own [theatre]. I also loved the idea of doing it in Alaska because there wasn't anything like it in Alaska. And so that gave me the ability to create, with other people, the kind of theatre company that I wanted to create.

I founded the Perseverance Theatre. I went back to Alaska with the purpose of starting the theatre and began gathering people around me that would help me make this happen. One was a person that my mother introduced me to and another was somebody that I met at a hot dog stand and another was someone that I taught in a class. And very quickly, it happened. I thought it would take five years to start the theatre, and within six months — boom! — we were there. My former husband and I brought 50 used theatre seats across the country with us to start the theatre.

| |

|

|

| The view outside the Perseverance Theatre |

MS: Yes. My mother and I fleeced $10,000 from my grandmother to help make this happen, and then I made all the people who were working with me in the theatre sign a contract that said that they would pay her back $50 a month until we paid it off. [Laughs.] The first show that we did was called Pure Gold, because my sister had said to me, "Why don't you do something about old people?" And I said, "Well, I really don't want to do Gin Game," but that set me off thinking. We were walking in the woods, and I said to her, "Oh, I could do something on the pioneers of this area. Maybe I could go out and interview people who are in their 70s and 80s and find stories about why they came to Alaska, bear stories, stories about the Chilkoot Trail, stories about the Native Americans, the Tlingit people," and just took off with that idea. So I interviewed about 35 old-timers, and then a friend of mine put it together in a reader's theatre piece, and I cast the six best storytellers, and eventually ended up performing, I think, over 300 times, did a statewide tour. It just caught the zeitgeist of the moment, because Alaska at that time — in the late '70s — it was really a young person's state. People were in their 20s and 30s, and there was a real hunger to hear from people who had lived in Alaska for years and who had basically founded it. You know, "How had they done it?" It was as if people were sitting around a camp fire listening to their grandparents, and it had a profound effect on people. We performed it in a church social hall, and the first night set up 50 seats and the next night 70 and the next night 90 and the next night 110, and pretty soon, there were lines around the block, and it was a phenomenon. And the night we closed it, I kept saying to one of my friends that a theatre needs a place to be. We've got stuff, we have to have a place. We can't be nomadic in church social halls. And she said, "Well, there's a space that's open across the water." It had the best pool table in town; it was an old bar. And we drove over that night and looked at it, and the guy said, "Okay, I can give it to you for $800 a month," and we said, "Sold!" And within 18 days we transformed it into Perseverance Theatre. And now it's still operating 32 years later.

So rare to have a permanent home that early.

MS: Yeah. Well, I think that's the Alaskan piece of it. I would say to people, "I want to do this," and people would say, "Yes!" or "Try it!" or "Why not?" I think that that's very much a Western mind. It's all about, "How do I make history?" whereas in the East Coast, it's more, "How does one fit oneself into history?" I don't know if Perseverance Theatre could have started any place else, and so quickly.

Do they own their own space now?

MS: Oh, yeah. We owned it within probably three or four years and then built another theatre on the back, a 180-seat theatre, and since then, there are apartments that have been built a few miles away for interns and for visiting artists and a shop. Yeah, it's just continued on.

| |

|

|

| Smith with Mead Center architect Bing Thom | ||

| photo by Scott Suchman |

Was your love for new American work formed early?

MS: It was really early for me. When I was here in Washington, DC, New Playwrights Theatre was a theatre that I greatly admired and I read plays for them, so that was when I was 22, 23 and carried that love with me to Perseverance Theatre. We started commissioning writers immediately, because I was really interested in finding an Alaskan voice in theatre. That's what I wanted to find. We commissioned Paula Vogel for How I Learned to Drive. That was a commission for her. [We] commissioned a lot of interesting writers. And then I started really tracking the Canadian writers and brought them to Alaska…John Murrell is one of my favorites…we premiered a new play of his, Democracy. Michel Tremblay, we did a couple of his plays. And you know, I direct at [Ontario's] Shaw Festival, too. I have more of a [freelance] career, in some ways, in Canada, working outside my own theatres, than I have had in this country.

Being an artistic director means you have to be social. It's a big part of the job: shaking hands with people. Do you view this as a necessary evil, or is meeting people something you genuinely love? Do you hate it?

MS: No, no, not at all. Not at all. My family is either lawyers or psychologists, and my dad was one of the early innovators and experimenters in group therapy, and I've always felt that my life in the theatre has a connection back to his experimentation with groups, that even though theatre isn't therapy, it can be therapeutic. And I think relationships with audiences — because I believe that what happens with art is it can heal people and it can change them — is really part of my work as an artistic director, talking to people and having conversations, whether it's the board, the staff or the audience itself. And because our audiences have so many stories to tell, too — our patrons have stories to tell — their interest in the arts [has] been a natural extension for me. I'm both an extrovert and an introvert — I kind of cross the line. So I can show both sides. I'm an introvert when I'm working. I can be a little more internalized [then], but I can be very extroverted as far as speaking to people, speaking to groups, having conversations.

Is raising money the major obstacle that American theatres face?

MS: I think the major obstacle that American theatres face now is twofold. I'd say finances is one, I'd say the other is growing new audiences. Part of what's happened is, we had a period of about 15 or 20 years when young people were not being brought into the theatre, and because of that, we see our audiences dropping off at different points. I believe that young people need to be branded with the theatre at an early age: their investigation of the theatre, or the understanding that the theatre is for them. Unless theatres have open doors to our young people, they may never come to see what we're doing and see that it's for them. There's always a dropoff when people are in childbearing years — when they are not at the theatre. This is young people in their 20s, 30s, maybe 40s, but oftentimes when people start reaching their late 40s and their children have gone on to college, there's a period of time where people begin looking inwardly again, and the theatre is a perfect vehicle for looking at stories that are about their lives, and I think that's when audiences come back to the theatre if they've been gone during the years when they have children. But I don't think they come back unless they have come when they've been young. So if we aren't building new audiences in the theatre — and that means large organizations like Arena and small organizations — then we won't have audiences in 20 years.

| |

|

|

| Eleasha Gamble and Nicholas Rodriguez in Oklahoma! | ||

| photo by Carol Rosegg |

MS: Absolutely. I think of Arena Stage as a feeder organization — that there may be many audience members who will come to see a production at an Arena Stage before they'll go to a smaller company. Our production, for example, of Oklahoma!, right now, is drawing audiences of all ages. I think it's really important, as a theatre that focuses on American work and American giants, that we produce brilliant geniuses like Rodgers and Hammerstein and are able to introduce a musical like Oklahoma! to a younger audience. Just a half an hour ago, I heard the matinee audience coming out for intermission, and the sound of young people laughing along with their teachers was glorious to hear. I know musicals had been done at Arena before your time, but I was surprised that your relationship to musicals is fairly new.

MS: Yeah. The first musical I directed, the first really good book musical, was South Pacific with Kate [Baldwin in 2002].

Was it scary to you? Was it an adventure?

MS: Well, my friends Gil and Jaylee Mead, and my partner, Suzanne [Blue Star Boy], had been encouraging me to direct a musical. For years, I really shunned musicals as not serious theatre, and boy, was I wrong. Somehow, I had it in my mind, because I was a child of the '60s, that serious theatre was only in drama, and when I began directing South Pacific, I woke up one morning about a week into rehearsal and just said, "I love directing musicals." I believe they're the most subversive art form that we have — they're subversive because we can say things in a piece of musical theatre that would be very difficult to say in a straight play. I believe that the musical art form, because it's kinetic, has an audience brought into the world of the musical through their bodies and through their hearts, in a different way than a straight play can bring them in, so it's been a really exciting journey for me.

You directed the world-premiere musical The Women of Brewster Place. I know that new musicals carry their own challenges. Working with living writers not being the least of it, but did it work new muscles for you?

MS: Absolutely. Absolutely, it did, and I loved working with [playwright-songwriter] Tim Acito and the whole wonderful cast on Women of Brewster Place.

Are there world-premiere musicals in the future of Arena Stage?

MS: Oh, yes. Definitely. Definitely. None that I can talk about right now, but yes, there are. [Laughs.]

Living in a city, we tend to lose our connection with nature. That seems really hard for you to do in Alaska, because nature's right there. Is the natural world important to you? Do you have a country house? Do you leave DC?

MS: Yes. Suzanne and I are building a cabin in Alaska, and every year, I take a month and go to Alaska without my cell phone, without a computer. It is a beautiful little cabin that sits on the Lynn Canal, and last summer when we were there building, outside there were 40 seals barking at us, and they were teaching a young seal how to throw fish in the air. There was a whale that came up the channel, grizzly bears in the area — there's a grizzly path behind the cabin. It's spectacular, it's vast, it's huge and it nourishes my imagination and my soul like nothing else.

Do you take plays there and read or do you try to decompress there?

MS: I completely unplug. [Laughs.]

I love that the beams of the new Mead Center resemble timber.

MS: Yes! [Laughs.] They're totem poles! They're story totem poles. Yes, oh, definitely purposeful. [Architect] Bing Thom and I are both from the Pacific Northwest — he's from Vancouver, I'm from Alaska, and I think there are a number of elements in the building that are very much about that part of the country. This is the first time that Parallam, which is what these totem poles are made out of, has been used in America. They're 95 percent old timber and five percent glue. They built a 65-foot lathe to create them, and there are 18 of them. It's beautiful, structurally, as you know.

(Kenneth Jones is managing editor of Playbill.com. Write him at [email protected].)