*

The stage and screen actor Jeffrey DeMunn has spent the better part of the past two decades toggling between powerful stage dramas, such as his current role as the iconic Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman (running through Feb. 27 at The Old Globe in San Diego), and film and TV work that mixes science-fiction and horror elements with soulful and moving stories. Many of those screen projects have been collaborations with director-writer-producer Frank Darabont. Those include two Oscar-nominated films "The Shawshank Redemption" and "The Green Mile," the 2007 adaptation of Stephen King's "The Mist," and the new zombie apocalypse TV series, "The Walking Dead," which blazed like a supernova last fall, premiering to record-setting audiences on AMC.

On the surface, it would appear that DeMunn's work in stage plays like Salesman, Arthur Miller's The Price, Thornton Wilder's Our Town, and David Hare's Stuff Happens has little in common with the kind of science-fiction fantasy roles that he's best known for on the big screen (note, DeMunn did score a 1995 Emmy nomination for playing a serial killer in HBO's "Citizen X"). But dig below the outer membrane (or the rotting zombie flesh, if you will), and you'll find there may be more in common between suicidal salesman Willy Loman and DeMunn's melancholic curmudgeon Dale in "The Walking Dead" than meets the eye.

The hit TV series may be rife with splattered blood and oozing guts, stomach-churning gore, and dead-eyed zombies being hacked to bits. But, at its beating heart, "The Walking Dead" is entirely human and very much alive — a character-based drama with tragic, classical undertones and timeless themes. Indeed, DeMunn draws definite parallels between his current stage and TV roles — one a naturalistic mid-century drama, the other a comic-book-derived post-apocalyptic nightmare happening in heightened reality.

"With 'The Walking Dead,' you could remove the zombies and put something else in their place — something that is putting human beings under stress, under pressure, putting them in a hard situation," DeMunn observes. "And then you watch and see how do they do — how do they survive, how do they treat each other? This is a timeless subject matter for drama: People under that kind of duress. If you take the Loman family and you remove the fact that he [Willy] is no longer relevant to the business that he is in, then there's no play. But if you bring to bear on those people some kind of pressure, then it's interesting. How are they going to deal with it? And it's something that Frank [Darabont] is fascinated with and has often written about in the past. So yeah, the show's not so much about zombies; it's really just about people."

| |

|

|

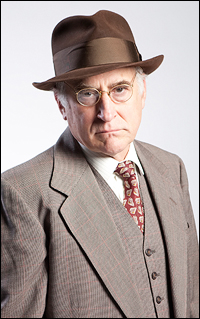

| Jeffrey DeMunn as Willy Loman | ||

| photo by J. Katarzyna Woronowicz |

The danger of playing Willy back-to-back in two different productions, DeMunn says, is not to rely on habits formed in the previous production, to try to rediscover the play all over again. "I don't want events, emotions, whatever from that previous production to intrude on this one. I need to start fresh and clean, or as clean as I can," he says. "So you need to be able to rediscover it each time, to be like a skier and find a little fresh snow on the slope every time you come down the hill. There's the danger that there are responses, thought processes, or emotional processes that I went through in the previous one that maybe aren't even appropriate now. So I have to be keenly aware of, to stay on top of, and have my ear attuned to that possibility, so that if stuff does start to repeat, I can sort of break it down and say, wait a minute, come on, let's take a fresh shot at this."

The role of Willy Loman is a titanic one. He's the psychologically-scarred deluded dreamer shifting back and forth between faded visions of a past too-good-to-be-true and the painful reality of his present mental state, which is threatening to come undone. In Arthur Miller's unflinching critique of the American Dream and the illusions that sustain it, Willy is the center around which his wife and two grown sons gingerly orbit as they engage in a desperate struggle to ground him in the present — a reality that's too hard for Willy to face. The play remains as resonant today as when it was first written in the late 1940s.

| |

|

|

| Jeffrey DeMunn on "The Walking Dead" | ||

| photo by Scott Garfield/AMC |

"I find that if I try to go big and understand the character in a really broad way, I just don't really have much capacity for that. That's not a talent of mine," he says. "So I just try to work it through the details and hope, in the sort of pointillist approach, that a general picture develops and appears out of my little details. That's basically what I do: 'What is happening right now? What just happened? What does my character want?'"

The biggest challenge of doing the role, DeMunn avows, is trying to navigate these rocky, larger-than-life emotions and yearnings inside of Willy and find what's at the heart of each. "The main thing is to simply continue to tell the truth despite the fact that you're going to such extreme emotions — such self-loathing, such anger at others, and such powerful feelings of futility and hopelessness and desire. The desires are so enormous," DeMunn says. "Willy doesn't just want to just live a good life and get along and come out the other end, and love his family, and be done. For Willy, it's got to be more, it's gotta be bigger, it's gotta be enormous. If he's going to drive a car, it's gotta be the best car made. But of course, nobody drives the best car. All cars have flaws. Life is filled with flaws and weaknesses."

The world has changed dramatically around the now 63-year-old Willy since his heyday as a traveling salesman. And he has struggled to keep up with the whirlwind changes in the culture and society — a theme that resonates boldly in an America where unemployment is rampant, the economy is stagnant, and much of the manufacturing industry has been shipped overseas during the past several decades.

"He bought into a system and succeeded very well at it. But the system of business has changed. And Willy doesn't change. He can't adapt to it. He doesn't understand it. It's confusing to him. And so he is left powerless in a world that used to be his kingdom," DeMunn says. "He had many visions of grandeur for himself — and I understand that. And much of what he says about himself and his past and his present is not true. It's what he would desire it to be. But there was a time when Willy Loman was a real kick-ass salesman. He did all right. People were glad to see him. People knew him. But now, the people that he grew up with in the business are dead. Or they're retired! And he's 63. And they're gone. All those people that he worked with, they loved him and respected him, and he loved and respected them. There was a sense of comradeship within that world that's now gone." DeMunn, who earned a 1983 Tony Award nomination for Best Actor in a Play for K2, admits that Willy's sense of dislocation is a feeling he can certainly relate to. "It's a little bit, I suppose, the way I sometimes feel if I go [audition for] a movie in New York, and I meet with the producers of [a film or TV series]," he says. "I look around the room, and they're all in their late 20s or early 30s, and they don't know me. I don't know them. A generation has passed, and now Willy's dealing with the new generation. And they know him only as someone who's passed his prime."

While Willy may be a man who struggled to adjust to a changed world, DeMunn has had the good fortune of working steadily for Darabont for the better part of two decades on films like "The Green Mile," "The Mist" and now the TV series "The Walking Dead." Indeed, Darabont has called DeMunn his good luck charm.

"If you just trace it, it's amazing," DeMunn says. "He doesn't use someone and then toss 'em. He finds someone whose work he likes, and he keeps at it. And look at lucky Jeff DeMunn! I've been fortunate enough to be able to work with him again and again over the years. I think that's an amazing quality that he has — fidelity. It's one of the things that Willy Loman finds so lacking in the world, and I feel very fortunate to have it in my life."

While DeMunn had starred in the 1988 remake of the classic B-movie "The Blob," for which Darabont had co-written the script, the two never met until DeMunn was cast by Darabont on the Oscar-winning film "The Shawshank Redemption" in 1994. Darabont wrote, directed and produced the film. From that moment, DeMunn knew that he had met a dear friend and trusted colleague. "He won my heart right away," says DeMunn. "I thought, this is a man I can work with. This is a man I can trust."

So when Darabont asked DeMunn if he wanted to play the role of Dale in "The Walking Dead," DeMunn immediately said yes. "He called me up and said, 'Do you want to come to Atlanta and kill some zombies?' And by now, I have enough experience with Frank to know that if he is throwing a party, I want to be there, because I know it's going to be spectacular."

DeMunn didn't know much about his part before he arrived in Atlanta, where the show is filmed. But he knew the quality would be high-level because Darabont was in charge.

The series, based on Robert Kirkman's comic books, centers on a band of survivors who have endured an apocalyptic event that's wiped out the majority of the human race and left them as brain-dead creatures that crave human flesh and blood. The show turns the standard zombie trope on its head to focus on the human side of the story — how people band together or tear each other apart when faced with extreme, life-threatening circumstances. The show's main character, Rick Grimes (played by Andrew Lincoln, of "Love Actually"), is a former cop who woke up from a coma inside a ravaged hospital only to learn the world as he knew it has ended. He eventually reunites with his wife and son, but the motley crew of survivors face a daily battle to stay alive.

DeMunn's character, Dale, is the salty, philosophical sage and de facto leader of the group who lost his wife to the deadly zombie virus and is essentially a broken man. When the series opens, Dale, who has ended up at the survivor's camp in his beaten-up RV, is beginning to bond with Andrea, a former civil rights attorney, and her younger sister Amy.

"Dale is a man who lost everything, because he lost his partner, his wife, that person with whom he was planning to spend the rest of his days," he says. "When that happened, he had nothing left emotionally. But it is within that cauldron of this post-apocalyptic world that he has started to come back to life again and to care again.

"It's like he now has nothing to lose, because he's lost everything. So he's not really afraid of anything. He can stick to his truth, to the truth of what he knows is right and good. He can care about other people, but he doesn't need anything from them. He's got no dog in the fight anymore, in a way. That's a little bit of the way I think of Dale. He's got no horse in the race, except that he has started to care deeply about the people around him. And his heart has come back to life, his soul has come back to life — in a world where people need some protection and they need somebody to keep an eye on them."

|

||

| DeMunn in Death of a Salesman |

||

| photo by Henry DiRocco |

After college, DeMunn got an audition in New York City with the prestigious Bristol Old Vic Theatre School in England. They only accepted two Americans a year, and scores of people auditioned. DeMunn didn't think he had a chance.

"On the afternoon I auditioned, for some reason I just leapt into the material and forgot utterly that I was auditioning," he recalls. "I forgot that I was doing anything except being the person that I was playing. I had never done that before. I had never been able to transcend the barrier of trying to do good so that they'll like me, trying to do what will please this person, trying to do a great audition, all those horrible barriers that get between an actor and their joy."

As luck would have it, DeMunn got accepted into the two-year program, which was just what he needed as an aspiring actor. "It took off a lot of my rough edges. I had a pretty high level of anger, and it helped me to cope with some of that," he says. "Plus, it was six days a week of a classical approach to acting. So I didn't have people teaching me how to feel, which I was not interested in. I wanted to know how to sit and stand and walk. And what do you do with your hands? Where do you look? How do you stay on a line of iambic pentameter? How do you say it? How do you say those words? How do you wear a Restoration costume? How do you do any of this? It was about craft. And I needed that."

After graduating from the Bristol Old Vic, DeMunn returned to the states and began touring with the non-union National Shakespeare Company, "which we called the National Paper Bag Company," he jokes. The company toured by bus to every state in the continental U.S., performing two Shakespeare plays and one other classical play every year. The actors did the sets, costumes, and everything. He was paid $148 a week, so it was a hardscrabble existence. But it was a formative and eye-opening experience. "I considered that to be the second half of my education. After two years of pretty superb six-day-a-week training in England, I then had to perform to high school kids in New Jersey," DeMunn explains. "And that's a really good oven to bake what you've learned in acting school. Because the stuff that doesn't work, you had to take it apart right away and come up with something new — and fast. It was trial by fire." Eventually, DeMunn moved to New York to see if he could make it in the theatre there. At that time, he says, it was a hell of a lot easier for a young actor just starting out than it is now.

"There were plenty of auditions that you could go to, and you didn't have to have an agent submit you for a showcase, which is usually the case now. You could just go and audition for showcases and get a part and do the part. I just started doing every bit of theatre that I could get my hands on. And then eventually I got a job doing a television movie with Lee Strasberg and Tony Lo Bianco."

While he certainly experienced moments of self-doubt during his early years in New York and often struggled, DeMunn gave himself plenty of leeway to succeed or fail on his own terms — to really give himself a shot to make it as a working stage or screen actor. The road manager with the National Shakespeare Company had given DeMunn some wise, matter-of-fact advice before he made his way to the Big Apple: "'You've got to give it ten years. And if after ten years you don't have something going [on], then you can get out and do something else."

"That took a lot of weight off my shoulders," DeMunn says. "So that way, I wasn't three years out, going, 'well, jeez, nothing's happening...I have no momentum. I don't know when I'll ever work again.' I didn't have to struggle with it because I'd been given a window of ten years."

DeMunn remembers in one week getting offers to do two plays — both on Broadway — after not being able to land anything for a long time. "I couldn't get in the offices of these people. They'd have a big slot outside their doors that looked kind of like a trash bin, and you'd slide your photo and resume in there. And you'd be checking the answering service every two hours. Did anybody call? There was a lot of that."

After that first Broadway show (the short-lived Comedians in 1976 starring John Lithgow and Jonathan Pryce), doors started to creak open. Of course, it helped that Mike Nichols had directed the play. "People who literally would not see me the week before were saying, 'Hey, Jeff! Come on in!' Like we were old friends? And I'd think, wait a minute...But I understand now that's the way the business works, and their job is to approach people and work with people who can do the job. And they had no idea if I could do anything. But having the endorsement of Mike Nichols, who cast me in that first Broadway show, then it was like, 'Oh well, if Mike Nichols thinks he can do it, then maybe he's OK.' So yeah, from there, a sense of momentum started to build."

By the early 1980s, DeMunn was well on his way. He earned a 1983 Tony Award nomination for Best Actor in a Play for his costarring role in K2, a drama by Patrick Meyers "about friendship and fidelity between two very different men stuck on the side of a 27,000-foot mountain in an impossible survival situation," says DeMunn. Two years before that, he had graced the big screen as Harry Houdini in Milos Forman's film adaptation of the novel "Ragtime."

The lessons that DeMunn learned in his early years still remain with him, especially as he brings to life one of the most iconic and monumental characters in American drama. In playing Willy in Salesman, DeMunn says that he's keeping it simple: "I'm just trying to look at the other people in the eye and tell the truth and see what we end up with. The script is so strong, the story is so strong, the desires are so enormous, and the failures and the weaknesses are so endemic, that the play just takes care of itself. So I just have to try to stay out of my own way."

Matthew-Murphy.jpg)