*

It isn't until page 135 of Arthur Bicknell's self-published "Moose Murdered, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love My Broadway Bomb"—a grisly chronicle of you-know-what—that the words "vanity production" appear. Still, this is perhaps the clearest and most candid discussion of a Broadway vanity production that you are likely to find.

Moose Murders, as you might recall, arrived at the O'Neill Theatre in the midst of the miserable winter of 1982-83. (It was the O'Neill's third play of the season. First, The Wake of Jamey Foster—Beth Henley's follow-up to the Pulitzer-winning Crimes of the Heart—opened in mid-October and lasted a mere 12 performances. This was followed by William Gibson's Miracle Worker-sequel The Monday After the Miracle, opening in mid-December and lasting an even more mere seven performances.) All told, the 1982-83 season had twelve shows that lasted less than a week, with six (including Moose Murders) closing after the opening night performance.

Eve Arden, the beloved big and small-screen comedienne of the 40s and 50s, played a disastrous preview on Saturday night January 29; returned Monday night for a second try, and then disappeared. Her departure was credited to a little problem with remembering lines, executing blocking, and apparently keeping track of the plot (for what it was worth). Emergency casting calls had already gone out, resulting in Holland Taylor, an already respected actress, but neither a star nor a star presence, rushing in, learning the lines over a week, and embarking on a second set of previews starting February 11.

Taylor was some thirty-five years younger than Arden, but Arden, at seventy-five, was perhaps a little old to play the mother of a precocious twelve-year-old. Let it be added that Taylor, who is now herself a septuagenarian, is currently giving a Tony-nominated performance at the Vivian Beaumont in Ann. Taylor was able to learn those lines, needless to say, and brought a good deal of professionalism to the affair. But Moose Murders was still Moose Murders; even the infamous Tallulah or the great Merman wouldn't have been able to make much of it, although they would presumably have gotten more laughs. The show played another eleven previews, making an ominously grand total of 13, and finally opened on February 22, only to close the same night.

Mr. Bicknell never reappeared on Broadway, and seems not to have written a professionally-produced play since. He has now—on the 30th anniversary of the birth and death of the Moose—given us a blow-by-blow (literally) description of the whole sorry affair. It is mighty desperate, and mighty funny.

|

||

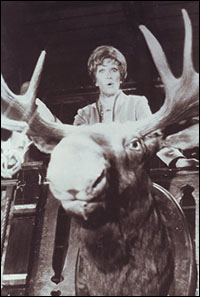

| Eve Arden in the original production |

||

| photo by Gerry Goodstein |

But a vanity production Legends was not. Kirkwood already had a Tony and a Pulitzer in his pocket for A Chorus Line, while Mary and Carol were both still in their prime—as ticketsellers, anyway. Moose Murders, on the other hand, pretty much defines the notion of vanity production. It was produced by something called Force Ten Productions, Inc., and one must always raise a suspicious eyebrow when an unknown and fully-funded producing concern comes to town with a negligible and hard-to-trace name. Force Ten, it turns out, was generated by money inherited from old-time Texas oil tycoon Hugh Roy Cullen. Cullen's granddaughter Lillie Robertson and her husband John Roach, neither of whom had ever produced on Broadway, optioned Moose Murders. Roach, who never directed on Broadway before or since, directed the show. Those of you who have access to the Broadway Playbill or poster will find at the bottom of the cast billing, "and Lillie Robertson," who met the same fate as her husband.

Welcome to the world of vanity productions.

Bicknell makes a delightful guide through this cautionary tale—he would almost have to, or why else would he write it?—and seems to have no misconceptions about the true nature of the project. Moose Murders was written as a satiric take on murder mystery plays; just how far, he seemed to wonder, could you go? It turned out: not far enough and too far at the same time. The author, looking back from today, seems to see and identify the myriad problems that occurred; his biggest surprise, apparently, was instantly finding someone who wanted to produce his script (and self-fund it, and direct it, etc.) on Broadway. And along Bicknell went, innocently enough, for the ride.

Moose Murders would not have succeeded if it were not a vanity production. It would presumably not have succeeded even if it had a more suitable star than Eve Arden. (Angela Lansbury and Colleen Dewhurst both had short-lived flops that fall which folded before the Moose unfurled.) This was simply a bad play, poorly done. Due to its ignominity, it hasn't quite died; Moose Murders was actually disinterred off-off-Broadway in January, with a script revised by Bicknell.

Arthur Bicknell's Moose Murders, no. But Arthur Bicknell's "Moose Murdered" will give you a good look at just what can go on in the glamorous, professional, so-called legitimate theatre.

|

||

| Cover art |

This bears some explanation. Simply put, the songwriter writes the songs and, if he or she is so equipped, prepares a comprehensive piano-vocal arrangement demonstrating just what he wants the listener to hear. These parts are handed over and transformed into rehearsal copies, often with edits and simplifications. Through the rehearsal period, these are altered and routined into the actual show versions, which are finally orchestrated. A piano-conductor score is also prepared; most conductors conduct from these rather than the full scores, as they provide an easy-to-read map to work from. These are used for piano-only rehearsals as well. Traditionally, Broadway vocal scores are developed from these piano-conductor scores and are thus reductions of the orchestrations.

In the case of the new Merrily, with Rilting's 2010 revised edition of A Little Night Music, the vocal score has now been prepared from Sondheim's own piano-vocals. Thus, you get to sit at the piano and play it the way Sondheim theoretically did, which makes a considerable difference. Rilting has at the same time used Sondheim's Merrily piano-vocals for a Revised Edition of the Vocal Selections. This is considerably expanded from the prior versions of the vocal selections, with fourteen songs (including two that have been cut over the years). So it is time for fans of the show (as it exists, not "like it was") to upgrade their Merrily.

Also of interest: The latest offering from the Applause Libretto Library—from Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, an imprint of Hal Leonard—is Lin-Manuel Miranda and Quiara Alegria Hudes' 2008 Tony Award winner, In the Heights. Limelight Editions, meanwhile, gives us "Shakespeare for American Actors and Directors" by Aaron Frankel. The latter includes a cover photo of a University of Minnesota BFA student playing Hamlet at the Guthrie in 2006. You may have heard of him. His name is Santino Fontana.

(Steven Suskin is author of the updated and expanded Fourth Edition of "Show Tunes" as well as "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," "Second Act Trouble," "A Must See," the "Broadway Yearbook" series, and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He can be reached at [email protected])