***

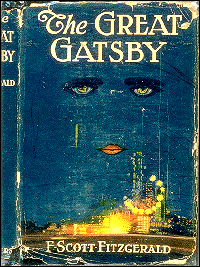

Andy Kaufman, the perverse comic genius, used to do a comic bit where he would step on stage with a copy of "The Great Gatsby" by F. Scott Fitzgerald in hand. After a few words with the audience, he opened it and began to read, sentence after sentence, page after page. He famously performed this act on "Saturday Night Live" once in the late 1970s. The crowd laughed nervously at first, Kaufman's behavior was so absurd. Then everyone grew quiet and confused, as it dawned on them that Kaufman wasn't going to shift into some other routine, but just keep on reading. Soon, the boos began. Eventually, an irate Kaufman offered the audience an alternative: if they liked, he would stop reading and instead play an album on a nearby turntable. The crowd cheered their approval of the latter choice. Anything but more Fitzgerald! Kaufman placed the needle on the LP. It was a recording of someone reading "The Great Gatsby."

Recently, I attended a performance of Gatz, the name of the six-and-a-half hour adaptation of the 1925 novel "The Great Gatsby," created by the quixotic downtown theatre troup Elevator Repair Service, and now playing at the Public Theater. Unlike the Kaufman act, there's no punchline, and the company reads the entire book, every "and," "the" and "said." Still, when I tell people about the production, the common reaction is that I must be joking.

During the dinner break between the first and second halves of the show, I went to an restaurant in the East Village. There I ran into a friend. I told him what I was doing. A fan of Fitzgerald, he showed interest until I told him how long the thing was. "A six-hour stage production of 'The Great Gatsby'?," he asked. Yes. "You mean a play of the novel?" Well, not exactly. They read from the book. "The entire book?" Yes. It takes place in an office, and the workers begin to play the characters. "They read the entire book?," my friend asked again. Yes.

|

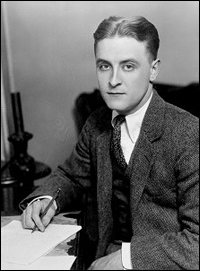

"The Great Gatsby" was Fitzgerald's third novel, and remains his most celebarated. In order to complete it, he took his wife Zelda to the south of France in 1924 for the summer. It's amazing to think today that among his reasons for this move was that the French Riviera was unfashionable, and therefore unpopulated and less expensive than living in New York. Fitzgerald knew his reputation rested on his novels. He resented having to churn out short stories for the magazines in order to pay the bills, but knew it couldn't be avoided. He and Zelda had a high standard of living which they couldn't seem to shake.

His first novel, "This Side of Paradise," had made his reputation as a spokesman of his generation, and set down a template for the Jazz Age flapper from which many young women drafted their personalties. His second, "The Beautiful and the Damned," was more naturalistic and mature, but sold poorly and was seen as a transitional novel. Much depended on book No. 3, which was variously titled "Among Ash Heaps and Millionaires," "Trimalchio," "Gold-Hatted Gatsby" and "The High-Bouncing Lover," before Fitzgerald's wise editor Maxwell Perkins insisted on "The Great Gatsby" being the strongest suggestion.

|

||

| F. Scott Fitzgerald |

Slowly, it is revealed that Gatsby has been nursing the illusion of his and Daisy's lost love for years. (He left for World War I and she, restless, married the wealthy Tom.). He gathered riches, through mysterious and probably illegal means, to impress her as a man of the world. Today, we are used to celebrities, politicians and other public figures reinventing themselves in the most extravagent terms, seeming to believe in each new incarnation of themselves as they unveil it the world. Jay Gatsby is their literary ancestor.

Trying on "Gatsby" for the stage is a brave act in itself. The works of Fitzgerald has also always resisted theatrical adaptation. "The Last Tycoon," Eliz Kazan's final film as director, was a famous flop in 1976. "Tender Is the Night" in 1962, starring Jennifer Jones and Jason Robards, failed. There have been three film versions of "The Great Gatsby," none particularly distinguished. The most recent one, in 1974, starred Robert Redford at Gatsby and Mia Farrow as Daisy, and was the subject of much ballyhoo, but died upon arrival. I also once saw a stage adaptation of the novel in Chicago, with Alan Ruck as Nick. It was strangely flat and lifeless, the aesthetic opposite the book.

The general problem with these various films and plays is that they must tell the story almost exclusively through dialogue and images. They strive to capture the jazz and tinsel of the time, the surface glamour. Lost is Fitzgerald's narrative, and the hundreds of details and cultural observations made by the narrator, Nick. It is this, the meat of the book, that captures the poetry, magic, madness, excitement and disillusionment of that heady, unbridled and careless moment in American life. Unlike, say, Charles Dickens, Fitzgerald's world cannot be sufficiently captured through conversation and characterization alone. The words that the writer put in the mouths of his characters are the least of his gifts. Gatsby famously says that Daisy's voice is "full of money." Similarly, Fitzgerald's voice rang with riches, but they are found on every page, not just in the plot.

Considering this, it can be argued that ERS's seemingly preposterous approach to the text actually stands the best chance of any adapation to getting the message and feel of the novel across. Not a page is sacrified, not one Fitzgerald phrase missed. We hear about the "yellow cocktail music"; what happens to a man when he turns 30; the famous tally of the guests at Gatsby's parties; Nick's memories of the Midwest; the watchful judging eyes found on a billboard for Doctor T. J. Eckleburg; and how we are all, in the end, boats beating against the current.

|

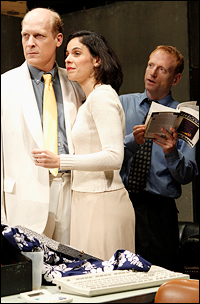

| Scott Shepherd, Annie McNamara, Kate Scelsa, Vin Knight and Laurena Allan in Gatz |

| photo by Joan Marcus |

|

||

| Jim Fletcher, Victoria Vazquez and Scott Shepherd in Gatz |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

As the story goes on, it seems to have an impact on the actual relationships between the people in the office. The person who appears to be the reader's closest friend in the office, for instance, takes on the role of Nick's girlfriend, golf pro Jordan Baker. Baker, in fact, is the only other performer who also reads from the novel, taking the book from Nick during Jordan's long account of when she first encountered young Daisy and Gatsby in Louisville, before World War I.

The only other major change in the narration comes during the last half hour of the show, when the actor playing Nick lays down the book and recites the last 30 or so pages of "The Great Gatsby" from memory. At this point, he seems more Nick than office worker. But then, during the course of the book's story, every person in that drab office has reinvented themselves, if only for a few hours. They have become more interesting, and, to judge by their faces, they seem to think more deeply about life.

When Scribner's published "The Great Gatsby" in 1925, editor Maxwell Perkins, who handled the works of Thomas Wolfe and Ernest Hemingway, feared the novel's success would be hurt by its slim length, a mere 200-odd pages. This relative brevity, of course, is what enables ERS to consider staging the whole thing in the first place — as was the case with the troupe's adaptation of "The Sound and the Fury," one of William Faulkner's briefer novels, a few seasons ago.

The first section of Gatz, so static for so long, hovers precariously on the edge of becoming an ordeal. It plays much like the first 50 pages of any novel one might pick up — that critical period when you're waiting for the story to kick in and the writing to transport you away. A lady next to me fought against sleep. But section two surprises one with activity. It is crowded with incident and inventive staging coups and theatrical leitmotifs. By section three, after the dinner break, the story has taken full command of your attention. There is commitment on either side of the footlights. Finally, during the final segment, the long, sad dénouement, it's just you and words again, with the show all but carried by Scott Shepherd, now as mournful and disillusioned as his character. By that time, the audience that surrounded me was rapt — even though, ironically, they really were watching nothing more than an actor reading a book to them, just as they had been six hours previously. It was storytelling time, nothing more. And the story was good.