*

Let it be stated, to begin, that people have been anxiously awaiting the CD debut of favored cast albums since 1988 or so, when the first CDs in their long cardboard boxes started claiming shelf space. Let us add that the last few years have, finally, brought us most of the must-haves. Recent additions include Anya and Illya Darling, both from Bruce Kimmel. Fittingly so, as he's the fellow who started the notion of dusting off non-blockbuster musicals and putting them on CD. His early label, Bay Cities, proved that people would eagerly buy CDs to replace cast albums they already owned, back in the days when we didn't quite know that vinyl would soon be obsolete.

(Older cast album collectors, by this point, had bought their Oklahomas and South Pacifics on 78s, early LPs, and later "stereophonically enhanced" LPs; so what was one more purchase?)

Bay Cities brought us A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Golden Boy, Celebration, Woman of the Year and Chicago — after which the labels decided that maybe they'd better retain their masters and do it themselves. Capitol and Columbia did just that, although they sabotaged themselves by surfeiting the market with dozens of titles within a couple of years.

At any event, many of the titles that stubbornly remained off the shelf — usually due to complicated legal tangles — are now in our collections, including such failed-but-intriguing musicals as Subways Are for Sleeping, Baker Street, Juno, Hazel Flagg, Make a Wish, Golden Rainbow, A Family Affair, Maggie Flynn and I Had a Ball. An increasing number of cast album CDs have already gone out of print; while a few have been repeatedly reissued on CD, other important titles are disappearing. So you might want to grab up titles like Anya while you can.

But let us turn to favored cast albums that have not yet been transferred to CD. (This list does not include items which

have been transferred to CD but are no longer available). We start out with

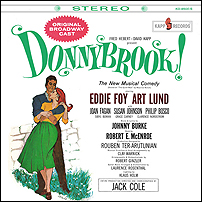

Donnybrook [KAPP KD-8500-S], the 1961 adaptation of the memorable 1952 John Wayne-John Ford movie "The Quiet Man." (One of the not-very-many John Wayne movies that we find watchable.) This is the one about the American boxer (played by Art Lund, from

The Most Happy Fella, in the musical) who — having killed a man in the ring — retires to Ireland. He falls in love with a comely lass (Joan Fagan), natch, but everyone thinks he's a coward because he won't engage in a big, wild, knock-down, drag out, swingin', swearin' donnybrook with her hard-headed brother. (Phil Bosco, of all people.) The score is by Johnny Burke, of Burke & Van Heusen but without Van Heusen; the songs are enjoyable, with something of a weakness in the big ballad department. This is one of those cast albums that are positively buoyed by the orchestrations. In this case they are by the great Red Ginzler, between

Bye Bye Birdie and

How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying.

Donnybrook can't begin to compare to those two tip-top musical comedies, but the orchestrations are in the same league. What

Donnybrook has, and how, is Susan Johnson. She plays a secondary role — that of a local widow — who tangles with a lovable ne'er-do-well (Eddie Foy, who received first star billing). Readers of this column have heard the name Susan Johnson from time to time; a chorus girl from

Brigadoon, she took over that show's comic lead Meg Brockie (in which she was apparently wonderful) and went on to one hit musical, playing the outspoken footsore waitress Cleo (from "Big D") in Frank Loesser's

The Most Happy Fella. Ms. Johnson has

Donnybrook wrapped around her proverbial little finger; you need only listen to this not-yet-on-CD LP to become an instant convert. She starts off the proceedings, or at least her part in the proceedings, with an excessively wry comedy song called "Sad Is the Day" in which she laments her skinflint husband's early death while not quite hiding the fact that she now is something of a merry and well-heeled widow. This is one of the items on Mr. Sondheim's list of "Songs I Wish I'd Written (At Least in Part)," and no wonder. She also has two delectable song-and-dance items with Mr. Foy, "I Wouldn't Bet One Penny" and "Dee-lightful Is the Word." Dee-lightful is the word, all right, for Ms. Johnson and for

Donnybrook.

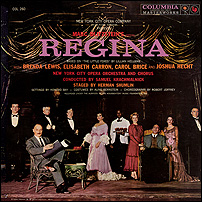

Next on the list is Marc Blitzstein's

Regina [Columbia O3S 202], a 1949 musicalization of Lillian Hellman's

The Little Foxes that manages to heighten the emotions of that already worthy melodrama.

Regina is a Broadway opera, really, although I suppose we should rather call it a rip-roarin' Broadway opera. (Place it with

Porgy and Bess, rather than the works of Menotti.) The original production was not recorded, although a few original cast selections were preserved with the composer at the piano.

Regina was soon remounted in several productions, including one by the New York City Opera in 1959. The Koussevitsky Music Foundation, most fortunately, underwrote a three-LP recording, easily among the top serious musical theatre recordings of the time. (Sergei Koussevitsky, long-time conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, was the composer's friend, mentor and publisher.) Blitzstein's score, with two dozen or so musical numbers, is stock-filled with highlights. The prelude, "Want to Join the Angels"; Birdie's opening number, "Music, Music"; Alexandra's "What Will It Be?"; Addie's mournful "Blues" ("Night could be time to sleep"); the "Rain" quartet; Regina's credo, "The Best Thing of All" and her rapacious waltz, "Things"; the Oscar-Leo scene in which father convinces his son to steal Horace's "Bonds"; Horace's final scene ("I'm Sick of You"), in which he suffers a fatal seizure; Birdie's aria "Lionnet," one of the most heartbreaking sequences in the American musical theatre; and last but not least, the Finale ("Certainly, Lord") in which Zan shows signs of triumphing over Regina.

The Columbia recording, under the direction of Samuel Krachmalnick (Bernstein's conductor for Candide), favors us with a clutch of memorable performances. Brenda Lewis, who created the role of Birdie in 1949, moves into Regina's shoes and gives a fiery performance. (Jane Pickens, of the Pickens sisters, originated the role. I once traveled to Washington to see Patti LuPone do it, which wasn't worth the trip. Joan Diener did it at the Michigan Opera in 1977, which sounds like interesting casting although I wonder whether she could actually sing it.) Joshua Hecht sings Horace, Helen Stine is Alexandra, and Loren Driscoll is Leo. Best, perhaps, are Elisabeth Carron (as Birdie) and Carol Brice (as Addie). Most surprising, by far, is George S. Irving giving a fine dramatic performance as Regina's grasping but pragmatic older brother Ben. To quote Larry Hart, I never knew he had it in 'im.

Several changes were made for the City Opera production, including the loss of the onstage Dixieland band and the "Chinkypin" sequence; this material is not included on the Columbia set, but no matter. A full restoration was performed by the Scottish Opera in 1991, and released on CD the following year by Decca. This is an ineffective reading of the score, though, sabotaged further by the sound (which makes it all but impossible to pick up many of the lyrics). The Scottish Regina might be preferable to no Regina at all, but the Columbia recording — and the Columbia cast — gives full value to Blitzstein's soaring score. In fact, I think I'll put on the final scene now, as I type. If there's one obscure musical theatre recording worth searching out, this is it.

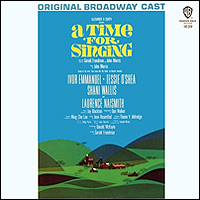

And then there's the big Broadway musical about a coal-mining disaster. Sounds cheery, no?

A Time for Singing [Warner Bros. HS-1639] was based on the 1941 film "How Green Was My Valley," a somewhat overlooked classic that took the Best Picture Oscar over "Citizen Kane" and "The Maltese Falcon." Things did not work so well on the stage in 1966, when Alex Cohen — whose musical track record was especially dire — produced it, or over-produced it, at the Broadway. There is a big, bouncy score from John Morris (one of Broadway's most accomplished dance arrangers of the time — with credits ranging from

Bells Are Ringing and

Bye Bye Birdie to

Mack & Mabel — and a top purveyor of Hollywood scores) and Gerald Freedman (best known as assistant to Jerome Robbins on

Bells Are Ringing,

West Side Story and

Gypsy). Freedman also directed and collaborated on the book, which might have given him too many hats.

A Time for Singing was ineffective in the theatre; the major reviews were universally poor. My understanding, though, is that the version of the show that Morris and Freedman presented in backer's auditions was a far finer piece of work than the big bouncing Broadway tuner the producer transformed it into. Toplining are Ivor Emmanuel, Tessie O'Shea, Laurence Naismith and Shani Wallis (who did considerably better in the motion picture version of

Oliver!). Ms. Wallis' performance of "When He Looks at Me," suitably preserved on the cast album, was described thusly by Walter Kerr: "obviously determined to bring the house down by compounding the more energetic qualities of Nellie Forbush and Eliza Doolittle, [she] skips, swings, kicks, thrashes, and in general lays waste to the Broadway stage until she has at last collapsed flat on her back, with her white petticoats showing, in a state of total, and hopefully adorable exhaustion." And Ms. O'Shea seems to be doing a bit of scenery chewing as well, in the title song. But the score, draped in Don Walker orchestrations, is well worth seeking out.

Another universally attacked musical came to the Broadhurst in 1970 under the title

Cry for Us All [Project 3 TS 1000]. Formerly

Who to Love?, originally

Hogan's Goat, from the well-received 1965 blank-verse play by William Alfred. This show would seem to have had a lot going for it, including a steamy story of political skullduggery in turn-of-the-century Brooklyn jam-packed with scandal, corruption, sex, and murder. What's more, it featured a score from the composer of one of Broadway's reigning smashes and one of its biggest song hits in years, which is to say Mitch Leigh of

Man of La Mancha and "The Impossible Dream." On the stage, though, things fell way flat. Robert Weede (former opera star who headlined

The Most Happy Fella and

Milk and Honey) and the above-mentioned Joan Diener (the fiery termagant who created the role of Aldonza in the Quixote musical) sang their way through the evening, complete with Ms. Diener getting to play Richard Kiley's last-act death scene this time around. (The late Ms. Diener was married to director Albert Marre, who had previously shepherded her and Kiley in both

La Mancha and

Kismet.) On stage,

Cry for Us All came across as a lumbering snooze with overly-melodramatic patches bringing forth unintended laughter; on the cast album, though, much of the score sounds mighty fine. I once talked to composer/producer Leigh about fixing up the show, if only because

Cry for Us All contains his most powerful and pleasing work since

La Mancha. He wasn't interested, alas, and has seemingly consigned the show to the back shelf with a "do not disturb" sign. A CD transfer of the score was announced — what, 15 years ago? — but was delayed and delayed and finally scuttled, presumably at the behest of Leigh. Think of how many musical theatre fans would love this score if only they had a chance to hear it.

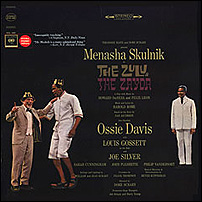

And then there's

The Zulu and the Zayda [Columbia KOS 6480]. I jest, you say? Well, no, I don't jest. The nearly-forgotten Harold Rome started his career small, in 1937 with the revue

Pins and Needles; moved on to a series of big (and sometimes lumbering) musicals, namely

Wish You Were Here,

Fanny, and

Destry Rides Again; and peaked with the unjustly-overlooked

I Can Get It for You Wholesale in 1962. After which he was virtually ignored. His one big show thereafter,

Scarlett, was produced in Tokyo in 1970, in London (as

Gone with the Wind) in 1972, and foundered on the road to Broadway in 1973. But in the meantime, Rome — who had a keen interest in African art and music — wrote a bunch of songs for Dore Schary's 1965 production of the comedy-drama

The Zulu and the Zayda. The Zayda being a South African/Yiddish grandfather (Menasha Skulnik); the Zulu being a domestic servant (Louis Gossett) with bones as earrings and shoes made of recycled automobile tires; and the events tied together by a more domesticated servant played by Ossie Davis, who co-starred with Yiddish Theatre great Skulnik. This all might not sound very promising, and the enterprise staggered through a not-well-attended five months at the Cort. The songs, though — featuring a mix of Yiddish and African themes — are tuneful, charming, and often lovely. Call me crazy, but I keep wanting to go back for "It's Good to Be Alive," "River of Tears," "Like the Breeze Blows," "Some Things," and "May Your Heart Stay Young (L'Chayim)." Our next column will continue this discussion, including some Off-Broadway and West End albums.

(Steven Suskin is author of "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations" as well as "Second Act Trouble," "Show Tunes," and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He can be reached at [email protected].)