Cinderella [Ghostlight]

Traditionalists, we have noted, generally tend to complain about revised versions of old musicals by revered masters. (Whether, we have also noted, they saw the original or not.) The new production of the 1957 musical Cinderella is no different, complaint-wise. But it is very different.

The first difference being that Cinderella andmdash; as written by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein andmdash; is not a Broadway musical. Or a stage musical, even. Julie Andrews attained overnight stardom when My Fair Lady opened in 1956, and CBS wanted to star her in a made-for-television special. How much more special than to get the reigning kings of Broadway to write a score for the newly-crowned queen? For Rodgers and Hammerstein this was a timely request; since 1951 they had come up with only two musicals, both poorly-received disappointments (Me and Juliet and Pipe Dream). For a pair accustomed to turning out a blockbuster every two years or so, this was a troublesome drought. There are several stories circulating about the genesis of the property, but it seems clear that the project began with the star rather than the writers.

Rodgers and especially Hammerstein knew how to write full-fledged, fleshed-out Broadway musicals. But that's not what they were attempting here. They were creating a fast-moving 90-minute TV special; after carving out time for the necessary commercials, that translated to 76 minutes of running time. Nowadays, we sometimes actually see Broadway shows of 76 minutes, but in 1957 it was unheard of to have a show that short. In fact, in those days the first act alone of most musicals averaged 75-90 minutes.

|

||

| Laura Osnes |

||

| photo by Carol Rosegg |

Unlike Gigi, Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella has had a strong presence since that first live telecast on March 31, 1957, which was the fourteenth anniversary of the opening of Oklahoma!, as it happens. London's Harold Fielding presented the first stage production on December 18, 1958 at the Coliseum, starring Tommy Steele. How to blow up the show to the proportions of a traditional Christmas pantomime? By devising a new book with Steele playing Buttons, a newly-invented servant to Cinderella's newly-invented father, the Baron. (Hammerstein was billed as lyricist, with no bookwriter credited.) And what to do about the skimpy-for-full-length score? Let Tommy sing "A Very Special Day" and "Marriage Type Love" from Me and Juliet, and also give the Prince that same show's "No Other Love." The latter, musically, was devised as a lilting WWII tango of the southern seas, "Beneath the Southern Cross," for the TV documentary series "Victory at Sea." Not quite Cinderella-flavored, but no matter. Steele also wrote himself an eleven o'clock number, "You and Me." This production was revived in London in 1960.

|

||

| Victoria Clark |

||

| Photo by Carol Rosegg |

The City Opera production was revived in 1995, after which came the Whitney Houston television version in 1997. This one added "The Sweetest Sounds" (from No Strings), "Falling in Love with Love" (from The Boys from Syracuse), and "There's Music in You" (which had been written for Mary Martin in the 1953 film "Main Street to Broadway"). A 2000 national tour — which briefly visited the Theater at Madison Square Garden in 2001 — starred Eartha Kitt as the Fairy Godmother; the City Opera offered their third production in 2004, also starring Kitt, and a 2008 Asian tour starred Lea Salonga.

|

||

| Laura Osnes |

||

| photo by Carol Rosegg |

Musically speaking, we have what might be called a split decision. The Cinderella score — that is, the portion of the score that Rodgers and Hammerstein actually wrote to be used in Cinderella — sounds pretty wonderful. The main songs — "In My Own Little Corner," "Impossible," "Ten Minutes Ago," "Do I Love You Because You're Beautiful" — are perhaps not ageless standards, but they work perfectly well and are overloaded with charm. David Chase has done an especially fine job on the adaptation — that is, translating the songs to fit the new book, altering the vocals, and transforming the tunes into dance arrangements. In this he is matched by orchestrator Danny Troob. (While Troob has spent many moons with Disney, we are pleased to report that this Cinderella sounds not like Disney, but like Rodgers and Hammerstein.) The work from Chase and Troob — on the original Cinderella songs, at least — really does sound like it would please Rodgers.

|

||

| Santino Fontana and Laura Osnes |

||

| Photo by Carol Rosegg |

What, one imagines, would Rodgers and Hammerstein make of all this? Songs that they themselves relegated to the discard pile, magically reappearing now? One assumes that they would have a problem of a different sort with what's been done to the "Stepsisters' Lament," here retitled "Stepsister's Lament." That's right. This delectable and perfectly-contrived duet, which must have pleased Rodgers and Hammerstein no end while they were writing it, and after, is now a solo. Not unentertainingly, but for no discernible reason (as the new libretto retains the two comic stepsisters). I don't suppose that Oscar Hammerstein was ever heard to utter "Ummm," but I can picture him saying, "Ummm...but that's not what we wrote."

Even so, the authentic Cinderella material on the CD sounds lovely, and Laura Osnes and Santino Fontana, who received Tony Award nominations for their efforts, do enchantingly well. Seeing as how they are both likely to go on to major Broadway careers (unless stolen away by sitcomland), you might want to go out of your way to make their acquaintance. As for this cast album, let's chalk it up as a grand success for fans of this "new" Broadway musical, even if several of the script and score choices leave some of us less than convinced.

|

||

| Cover art |

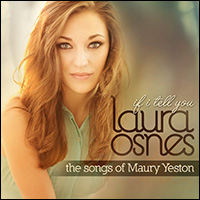

Between creating the roles of Bonnie (as in Bonnie and Clyde) and Cinderella (as in Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella), the above-mentioned Osnes was omnipresent on the special events scene. Pipe Dream at Encores, The Sound of Music at Carnegie Hall, a showcase of her own at Cafe Carlyle and more. Included among her engagements was "Laura Osnes Sings Maury Yeston" last November at 54 Below. Osnes and Yeston, it turns out, are a pair well met. Mutually pleased with the results, the composer not only decided to bring the singer into the studio; he wrote two new songs for the occasion, one of which, "If I Tell You," serves as the album title. The entire CD is good enough to prevent me from citing separate tracks, although I am pleased that Osnes has seen fit to sing one of my favorite Yeston songs (the superb "New Words," from the problematic In the Beginning). None from the haunting Death Takes a Holiday, though, and nothing whatsoever from Yeston's little-known but worthy Phantom — both with leading roles that would suit Osnes.

The heart of "If I Tell You" (ten of 17 tracks), consists of Yeston's 1991 song cycle "December Songs." I must confess that I was unimpressed when I first heard these sung by Andrea Marcovicci, who introduced them at Carnegie Hall; so much so that I haven't listened to them since. Blame me, or blame Marcovicci, but they left me cold as, well, December in Central Park (which is where the cycle is set).

My disappointment at the time was that the songs somehow "didn't sound like Yeston." With Osnes, though, the cycle is compelling, dramatic, comic and altogether engaging. So in addition to giving us a fine collection of the songs of Maury Yeston, Osnes — for me — rescues "December Songs" and adds it to my favored Yeston shelf.

(Steven Suskin is author of "Show Tunes" as well as “The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations,” “Second Act Trouble,” the "Broadway Yearbook" series and the “Opening Night on Broadway” books. He can be reached at [email protected].)